As the poll observer listened sympathetically, the rural priest diagnosed the root of Russia’s social problems in “the decay of all the old supports: religion, family, morality, the traditional way of life.”1 An election of representatives to the Russian State Duma was underway, and the man the bearded priest was talking to—Professor Sergei Bulgakov, an Orthodox Christian intellectual and future theologian—was observing the vote in Crimea. While the priest’s lament sounds like a textbook complaint of contemporary social conservatives, the year was 1912.

Social conservatives have been focusing on the family for a long time, and Russians have frequently been at the forefront of the fight for “traditional” values. In more recent times, Russian conservatives were central to the founding and operations of the World Congress of Families (WCF), a Christian-dominated inter-confessional coalition of right-wing activists from around the world dedicated to defending what they call “the A concept of family, used by the Christian Right, defined by traditional gender roles frequently used to advance an anti-LGBTQ, anti-feminist, “family values” agenda. Learn more ,” that is, a nuclear family consisting of a married man and woman and their children. When the coalition met for its ninth global conference this October in Salt Lake City, Utah, several Russian activists numbered among the speakers, including Alexey Komov.

Komov is WCF’s Regional Representative for Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States; the Howard Center for Family, Religion and Society’s representative to the United Nations; and a member of the Russian Orthodox Church’s Patriarchal Commission on the Family and the Protection of Motherhood and Childhood. He was in Utah to speak about “The Family in Europe—Past, Present, Future,”2 and during his presentation, he touted Russia’s leading role in the global “pro-family” movement today, emphasizing that the nation’s Communist past has given Russia and other Eastern European countries a taste of the dangers supposedly inherent in secularism, which “more naïve” Westerners might miss. As a result, he maintained, “Eastern Europe can really help our brothers in the West” to resist the “new totalitarianism” associated with “political correctness” and the sexual revolution.3

In addition, Fr. Maxim Obukhov, the director of the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC), Moscow Patriarchate’s Department of Family and Life, attended and received the 2015 Pro-Life Award for his longtime involvement in prominent Russian organizations that oppose abortion and promote the “natural family.”4

“It would be a mistake to think of the relationship between U.S. and Russian social conservatives as something of one-way influence, or to look at Russian social conservatism as essentially confined to Russia itself.”

WCF IX represents an opportunity to consider the outsized role contemporary Russia plays in the global culture wars, with particular attention to two related questions. The first is whether Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the subsequent chill in U.S.-Russian relations represents any kind of turning point for the collaborative efforts between Russian and U.S. social conservatives, and particularly the impact of the removal of WCF’s official imprimatur from what would have been WCF VIII in Moscow, but instead became billed as an international forum called “Large Families: The Future of Humanity.” The second and more interesting question regarding the relationship between the U.S. and Russia with respect to the global culture wars was posed two years ago by Political Research Associates’ Cole Parke: “When it comes to the culture wars, who’s exporting and who’s importing?”5 As Komov’s words suggest, contemporary Russian conservatives certainly don’t see themselves as solely on the receiving end of this international movement.

Very important work has been done on the efforts of American social conservatives to export far right ideology in connection, for example, with Uganda’s infamous “Kill the Gays” bill.6 It is also the case that U.S. social conservatives helped lay the foundations for resurgent social conservatism in post-Communist Eastern Europe and Russia. Russian Orthodox Christian journalist and commentator Xenia Loutchenko, who has researched some aspects of Russian-American collaborative culture warring efforts,7 assesses American influence in the early post-Soviet days as particularly important with respect to building the Russian A movement that emerged in the aftermath of Roe v. Wade, a decision which prevented states from outlawing abortion under most circumstances. Learn more movement (for which Fr. Maxim Obukhov was honored at WCF IX).

Nevertheless, as Loutchenko and I also discussed in an interview conducted in Moscow in May 2015,8 it would be a mistake to think of the relationship between U.S. and Russian social conservatives as something of one-way influence, or to look at Russian social conservatism as essentially confined to Russia itself.9 Seriously considering Russia’s influence on international social conservatism, both historically and in our own time, presents new ways of thinking about the global culture wars—as well as important insights for how progressive activists might strategically resist the international Right’s global encroachment on human rights.

“Guiding this fear was the idea that, absent absolute values grounded in unchanging religious truth, human morality will decay and society will descend into chaos.”

Russian Religious Conservatism in Historical Context

It’s no coincidence that the idea to found WCF was hatched in Russia in 1995, as the result of discussions between Allan Carlson, then president of the Rockford, Illinois-based Howard Center for Family, Religion and Society, and Anatoly Antonov and Viktor Medkov, two professors of sociology at Lomonosov Moscow State University.10 Nor is it coincidental that Carlson was heavily inspired in the first place by the Russian-born conservative sociologist Pitirim Sorokin, longtime head of the Sociology Department at Harvard, where Sorokin worked from 1930-1959.11 Throughout his years in the West, Sorokin consistently exhibited concern about the ostensible crisis of Western culture, which he linked to the “collapse of the family” in books such as his 1947 Society, Culture, and Personality: Their Structure and Dynamics, a System of General Sociology and his 1956 The American Sex Revolution.

Sorokin’s work represented a continuation of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century European attempts to defend a role for the realization of spiritual values—in some cases explicitly for Christianity—in society and governance. This discourse was developed, with substantial Russian participation and influence, in response to revolution, secularization, and what I have described elsewhere as the “perceived cultural threat of nihilism.”12

Guiding this fear was the idea that, absent absolute values grounded in unchanging religious truth, human morality will decay and society will descend into chaos. Sexual “permissiveness” is of particular concern, because it supposedly indicates a reversion to an animalistic nature that only higher values are capable of countering. As the fin-de-siècle Russian Christian philosopher and apologist Prince Evgeny Nikolaevich Trubetskoi put it, “Faith in the ideal is that which makes man human.”13 Similar sentiments, including in the writings of Trubetskoi and Bulgakov, were often tied to the concern that in a society without prevailing spiritual values, the state will be elevated to the status of a god, an idol that would encroach utterly on human freedom. As the fictional revolutionary conspirator Shigalev put it in Dostoevsky’s 1872 novel Demons, “Beginning with absolute freedom I conclude with absolute despotism. And I would add that apart from my solution to the social question, there can be no other.”

Christian critics of 20th-century totalitarianism advocated the realization of religious values in society and statecraft on precisely these grounds, arguing that godlessness would inevitably lead to tyranny by making the state into an idol. T. S. Eliot, for example, argued in a 1939 series of lectures that a critical A neutral term used to describe someone or something, such as in law, as non-religious in character. Learn more liberalism was inherently unstable—it would have to be replaced by something with substantive content, and if that something were not religion, then it would be the “pagan” A form of far-right populist ultra-nationalism that celebrates the nation or the race as transcending all other loyalties. Learn more of Germany or Italy, or the Communism of the Soviet Union.14 While Eliot referred to the French Neo-Thomist theologian and personalist philosopher Jacques Maritain as an influence, we know that Maritain was heavily involved in dialogue with Russian exiles in Paris,15 not least the Christian existentialist Nikolai Berdyaev, who had made a very similar argument to Eliot’s in his 1924 The New Middle Ages (translated into English in 1933 with the title The End of Our Time). Berdyaev would exert considerable influence on American understandings of Russian history and on religious anti-Communism.16 Meanwhile, the refrain about the state becoming an idol has become a staple of conservative defenses of “religious freedom.” As Tucker Carlson put it in April 2015, in defense of the supposed right of businesses not to hire atheists, “If there’s no God, then the highest authority is government.”17

“Russian concerns about public morality have never been only about Russia, but have always been bound up with considerations of the role that Russia should play in the wider world.”

But to return to Berdyaev and his relationship to the contemporary Russian Right, it is important to note that he was not only an advocate of a religious society, but also of a kind of Russian national Belief in a chosen one who signals salvation, e.g. a herald, prophet, or avatar. Learn more . That is, he (along with Bulgakov and others) believed in a particular Providential calling for Russia, and, while opposing the Bolsheviks, they looked forward to a future in which a spiritually renewed Russia would have an important role to play in reviving the Christian roots of European civilization.18 The key point here, even more than any specific understanding of family relations, is the idea of a special role for Russia in the world’s moral progress—an idea that, despite the intellectual contortions that thinkers like Berdyaev and Bulgakov went through in attempts to avoid charges of chauvinism and The belief in the primacy of “the nation” as the most important political allegiance, that every nation should have its own state, and that it is the primary responsibility of the state and its leaders to preserve the nation. Learn more , all too easily play into a sense of Russian exceptionalism: a sense that Russia represents a morally superior civilization.

With or without claiming inherent moral superiority, in any case, there is a clear claim here that Russia has a spiritual mission to enlighten other nations. Historically, this claim is rooted in Slavophilism, a nineteenth-century Russian form of nationalist thinking that asserted that Russia had a special path of development and represented a more holistic, harmonious, moral civilization than that of the Latin West. Instead of the West’s calculation, capitalism, individual rights, contracts, and “rationalism,” Russia had “sobornost.” A nearly untranslatable term, sobornost was invoked by Aleksey Khomyakov and other Slavophiles to mean a kind of collective social harmony in which individuals realize themselves organically as a part of the community, a concept that was meant to contrast with the individualism that supposedly characterized the West.

The collapse of the Soviet Union brought with it an upsurge in interest in Russian religious and émigré thought, already known to Soviet dissidents in samizdat (the underground reproduction of censored publications across the Communist bloc). In the 1990s, there was a widespread sense that perhaps these thinkers had preserved a more authentic form of Russian thinking and culture. Russian nationalism was on the rise—its official suppression had been a source of tension in the USSR—and some Russians gravitated to the messianic conceptions of intellectuals like Bulgakov and Berdyaev, or the much more radically conservative monarchist Ivan Ilyin, for ways to conceptualize Russian greatness. And that greatness could not be conceptualized apart from a mission that was larger than Russia itself.

Along with post-Communist concerns about a “demographic winter”—the idea that the West is suffering a “birth dearth” of too few babies as a result of secular values and the embrace of progressive sexual mores19—the Russian discourse of moral mission and the superiority of Christian values to those of the “decadent” West has played a key role in the resurgence of social conservatism in post-Soviet Russian society. It should be noted that this discourse is essentially imperial; Russian concerns about public morality have never been only about Russia, but have always been bound up with considerations of the role that Russia should play in the wider world. One of the most influential exponents of this exceptionalist discourse today is the neo-Eurasianist Alexander Dugin.20

These days, these sensibilities get a boost from Russian political leaders as well. Not only has Dugin had Russian President Vladimir V. Putin’s ear,21 but Putin also sent the leadership of the currently-ruling United Russia Party books by the nineteenth- and twentieth-century Russian religious philosophers Vladimir Solovyov, Berdyaev, and Ilyin as New Year’s presents in 2014. These three intellectuals had varying approaches to theology and politics—the Christian socialist Berdyaev and the monarchist Ilyin hated each other—but all of them advocated the integration of religious values in society and governance.22 In his third term in office, Putin has worked very closely with the leadership of the Russian Orthodox Church, Moscow Patriarchate, and Russian plutocrats to promote social conservatism at home and abroad. The latter include figures such as “God’s oligarch,” Konstantin Malofeev,23 the successful founder of Marshall Capital Partners who is known for investing his fortune into Orthodox Christian and social conservative initiatives, such as the Russian Society of Philanthropists for the Protection of Mothers and Children, the Safe Internet League, and the YouTube channel “Tsargrad TV,” which Loutchenko has described as an attempt to build a Russian FOX News.24 It also included former Russian Railways President Vladimir Yakunin. (Yakunin is on the U.S. sanctions list for his closeness to President Putin, while Malofeev has been sanctioned by the European Union in response to accusations from the Ukrainian government that he was financing the rebels in Donbas.) This elite backing lends considerable oomph to Russian social conservatives’ international efforts, making it all the more important for advocates of human rights to be aware of them.

“The ‘Punk Prayer’ performance led to new legislation, enacted in June 2013, that made it a crime to insult religious believers’ feelings.”

Russia’s Hard Right Turn

Since the end of 2011, when tens of thousands of Russians participated in mass protests against election fraud, Russian social conservatism’s star has risen within Russian circles of power. The late-2011 protests continued into 2012, ahead of the election of Putin to a third term as president. Perhaps feeling betrayed by the middle class his policies had helped create, representatives of whom made up the bulk of the protesters, Putin took a populist, nationalist turn, identifying himself more closely with the Orthodox Church and expecting its absolute loyalty in return. This became abundantly clear that February, when members of the feminist punk collective Pussy Riot famously demonstrated in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior, performing their “Punk Prayer” to condemn Patriarch Kirill, head of the Russian Orthodox Church, for backing Putin’s candidacy. (Three members of the collective were sentenced to two years in penal colonies for “hooliganism motivated by religious hatred”—one was freed on probation—with the vocal support of some U.S. conservatives like Concerned Women for America’s Janice Shaw Crouse.25 Two would emerge to international celebrity.)

The “Punk Prayer” performance led to new legislation, enacted in June 2013, that made it a crime to insult religious believers’ feelings. But the law was just one expression of what Russian political commentator Alexander Morozov has called a “conservative revolution,” marked by populist rhetoric Blaming a person or group wrongfully for some problem, especially for other people’s misdeeds. Scapegoating deflects people’s anger and grievances away from the real causes of a social problem onto a target group demonized as malevolent wrongdoers. Learn more political opponents and the An umbrella acronym standing for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning. Learn more community, which began with Putin’s third term.26 There was also the Dima Yakovlev Law, Russia’s ban on the adoption of Russian children by U.S. citizens, which passed the Russian State Duma and Federation Council in late December 2012 and took effect on January 1, 2013. The Russian president’s children’s rights ombudsman, Pavel Astakhov, pushed hard for this law, promoting it not only on the grounds of individual cases of abuse and neglect involving Russian children adopted by Americans, but also on the basis of opposition to potential adoption of Russian children by same-sex couples.27 While this law could hardly have been well-liked by many American social conservatives—Russia was a popular country for American evangelicals seeking to adopt foreign children—National Organization for Marriage President Brian Brown actually joined a delegation of French members of the National Front in Moscow, where he encouraged the passage of the law because it would keep Russian children from going to countries that allow same-sex couples to adopt.28

June 2013 then saw the passage of Russia’s federal law “for the Purpose of Protecting Children from Information Advocating for a Denial of Traditional Family Values,” popularly known as the “anti-gay propaganda law,” which bars vaguely defined “propaganda” of “non-traditional” sexual relations to minors, effectively making it illegal to provide LGBTQ teenagers with life-saving information.29 Members of the United Russia Party quickly fell in line with the changes originating at the top, and so opposition to such moves was eliminated from the political center amid increasing rhetoric about ‘national traitors’ and ‘fifth columnists.’ In Morozov’s view, the Russian political center is now “full of supporters of global ‘conservative revolution.’”30

“Meanwhile, direct Russian government collaboration with the Orthodox Church has proceeded apace in matters of both domestic and foreign policy.”

Meanwhile, direct Russian government collaboration with the Orthodox Church has proceeded apace in matters of both domestic and foreign policy. Pavel Astakhov’s position on “children’s rights” is actually an essentially radical doctrine of state non-interference in family matters—that is, despite staggeringly high rates of domestic abuse in Russia, he is opposed to any legal enshrining of the term “domestic abuse” on the grounds that it is an affront to the sacrality of the (“natural”) family and paves the way for undue state interference in parents disciplining their children. In this respect, Astakhov’s official pronouncements parrot the ideas of the far right Archpriest Dimitry Smirnov, head of the ROC’s Commission on Family Matters and the Protection of Motherhood and Childhood, who frequently has Astakhov’s ear.31

As Sergei Chapnin has astutely observed, the ROC has coordinated with government propagandists to promote patriotism and traditional values. Chapnin writes, “Beyond liturgy and piety, other traditions were revived: respect for the family, opposition to abortion,32 the banning of homosexual practice and propaganda. These measures are seen as asserting traditional Russian mores in opposition to the decadence of the West.”33

But Russian conservatism isn’t just defensive. As Chapnin explains, there’s an imperial element as well:

The Church has taken on a complex ideological significance over the last decade, not least because of the rise of the concept of Russkiy Mir, or “Russian World.” This way of speaking presumes a fraternal coexistence of the Slavic peoples—Russian, Ukrainian, Belarussian—in a single “Orthodox Civilization.” It is a powerful archetype. It is an image of unity that appeals to Russians, because it gives them a sense of a larger destiny and supports the imperial vision that increasingly characterizes Russian politics.

This imperial ethos was certainly on display in what would have been WCF’s eighth annual meeting in 2014, when the World Congress of Families had planned to head back to its birthplace in Russia. Those plans, however, took a different turn.

“American Christian culture warriors also sometimes took credit for Russia’s conservative legislative onslaught.”

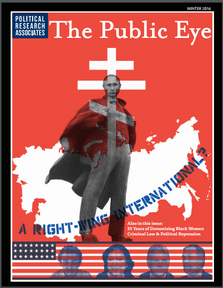

Global Social Conservatism in Putin’s Third Term – A Right-Wing International?

Prior to the annexation of Crimea, Putin had received a substantial amount of praise from representatives of the U.S. Often used interchangeably with Christian Right, but also can describe broader conservative religious coalitions that are not limited to Christians. Can include right-wing Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Mormons, and members of the Unification Church of Sun Myung Moon. Learn more , even if some mistrusted his KGB past. President and CEO of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, Franklin Graham, for example, could not resist praising Putin for the passage of Russia’s anti-gay “propaganda” law, declaring that Russia was acting more morally on this issue than the United States, despite his reservations about Putin’s Soviet background.34 American Christian culture warriors also sometimes took credit for Russia’s conservative legislative onslaught. For example, Scott Lively, a A movement that emerged in the 1970s encompassing a wide swath of conservative Catholicism and Protestant evangelicalism. Learn more author and activist who is currently being sued for crimes against humanity for his involvement with the Uganda “kill the gays” bill and who has traveled to Russia and Eastern Europe on more than one occasion, claiming credit for the passage of the anti-gay “propaganda” law.35

Despite examples of claims to have exported their initiatives to Russia, however, U.S. social conservatives also frequently recognized Russia’s agency and leadership in global social conservatism. WCF Managing Director Larry Jacobs minced no words when he reiterated the Russian messianic trope described above, declaring on End Times Radio in June 2013, “The Russians might be the Christian saviors of the world.”36 Likewise, it was not an affect, or mere diplomacy, when American anti-LGBTQ crusader Paul Cameron proclaimed to the Russian State Duma that he had come “to thank the Russian people, the State Duma, and President Putin… in the name of the entire Christian world” for Russia’s active legal Repression occurs when public or private institutions—such as law enforcement agencies or vigilante groups—use arrest, physical coercion, or violence to subjugate a specific group. Learn more of LGBTQ rights.37

A few months after Cameron’s visit to Russia, however, it became more complicated for Russian and U.S. social conservatives to unite, making it momentarily possible to hope that international tensions might hamper the effectiveness of the global culture wars. In our interview in May 2015, Loutchenko and I speculated that 2014 might have represented a turning point in this regard. Although subsequent events have shown that many American social conservatives are more than willing to work with Russia, when Russia annexed Crimea in March 2014, the world at large reacted with alarm, and the conservative “pro-family” world became divided. WCF had planned to go back to Russia that coming September for its eighth conference, but Putin’s brand had now become toxic to enough conservatives to make this difficult, even apart from any fear of the possible violation of U.S. sanctions against Russia. WCF withdrew its official sponsorship from the event, releasing a statement explaining that their withdrawal was made necessary by practical considerations, but which also went out of its way to praise Russian churches and individuals for their “leadership role in the fight to preserve life, marriage, and the natural family at home and as part of the international pro-family movement.” It added, “The World Congress of Families takes no position on foreign affairs, except as they affect the natural family.”38 Other social conservative groups were not so sympathetic. Concerned Women for America pulled out of the event altogether, with its CEO and president Penny Nance declaring that her organization did not “want to appear to be giving aid and comfort to Vladimir Putin.”39 (Subsequently, articles in the conservative journals First Things40 and American Conservative41 have warned against the religious nationalism of Putin’s “Corrupted Orthodoxy” or “Orthodox Terrorism.”)

“To Russian and U.S. social conservatives, a key takeaway from the forum was the impression that, while Russia is very happy to be working with foreigners in the fight for the so-called ‘natural family,’ it is Russia that is at the helm.”

It wasn’t that CWA or other social conservatives who turned against Russia now objected to Russia’s hard anti-LGBTQ line, of course. It was that the annexation of territory in violation of international law revived Cold War era right-wing perceptions of Russia as a threatening state that is not to be trusted. (In this regard, it should not be forgotten that American Christians have missionary ties to Ukraine, which is also a popular country for U.S. adoptions.) Nevertheless, the American leaders of WCF stuck by their Russian partners. The meeting went forward, but not as an official WCF conference. Instead, the conference was titled “Large Families: The Future of Humanity.” U.S. WCF leaders remained intimately involved, with Communications Director Don Feder and Managing Director Jacobs on the organizing committee.42 The event depended for its financing primarily on Russian oligarchs Yakunin and Malofeev.

Meanwhile, the lack of international approval for the renamed WCF VIII most likely emboldened Russian social conservatives in their claim to global leadership in the fight against abortion and LGBTQ rights—a claim that WCF’s American leaders and their fellow conservative comrades, apparently untroubled by Russia’s increasing anti-Westernism, had already recognized. For example, some Russian speakers highlighted the changed circumstances of the conference as proof that Russia was a global leader in tackling problems other countries wouldn’t face. As one of the first speakers, Duma deputy Yelena Mizulina, who authored the anti-gay “propaganda law,” proudly announced, an event like this one, which took place in the Kremlin and the Cathedral of Christ the Savior (where the Pussy Riot protest took place), most likely could not take place in Europe or the U.S. in their current climates.

Last year’s WCF in Salt Lake City may belie Mizulina’s statement to some extent—WCF IX demonstrated a clear attempt to tone down Hard Right rhetoric43—but her claim matters. To Russian and U.S. social conservatives, a key takeaway from the forum was the impression that, while Russia is very happy to be working with foreigners in the fight for the so-called “natural family,” it is Russia that is at the helm. WCF’s Larry Jacobs admitted as much when he stated at the event, “I think Russia is the hope for the world right now.” Invoking Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Jacobs went on to explain that since Russia had defeated Marxism, it could help the West defeat “cultural Marxism” today—a nearly identical claim as that which Alexey Komov made this past fall at WCF’s meeting in Salt Lake City.44

And Russia is clearly pushing forward with this agenda on the international stage, with Komov in a leadership role. Take, for example, Russia’s role in securing the passage of a UN Human Rights Council resolution on “Protection of the Family,” which defined the family “as the fundamental group of society and the natural environment for the growth and well-being of all its members and particularly children.”45 This resolution, sponsored in part by Russia—whose influence at the UN is bolstered by its permanent seat and veto on the UN Security Council—was clearly understood, by both supporters and opponents, as an attack on individual rights and a win for supporters of the “natural family”46 (which implicitly excludes families headed by same-sex couples). Komov has bragged of his part in delegations to the UN, which included Russian political leaders Mizulina and Astakhov, in which they pursued similar goals.47

“This right-wing iteration of moral exceptionalism entails a belief that Russia was given a Providential calling to revive the Christian roots of European, or more broadly Western, civilization”

Meanwhile, when I spoke with Russian commentator and researcher Xenia Loutchenko in May, she highlighted Russia’s success in attracting members of the European Right, mentioning that the French National Front recently took millions of dollars in loans from a Russian bank, in what many saw as a reward for the National Front’s support for the annexation.48 She also described Yakunin’s World Public Forum, which hosts an annual “Dialogue of Civilizations” in Greece, as a “right-wing international.” The phrasing might be hyperbolic, with its invocation of the Soviet-dominated Comintern, or Communist International, which was dedicated to spreading Communism around the world from the 1920s-40s. Nevertheless, drawing a comparison between the Comintern and the contemporary global culture wars, in which Russia is playing a leading role that is far from entirely derivative, makes a valid point. We will not be able to grasp Russia’s role in the global culture wars if we persist in treating Russia as essentially a recipient of America’s exported culture wars, and not an independent actor, and even exporter, in its own right.

The recent Cold War past makes it difficult for some, on both the Left and the Right, to imagine contemporary Russia as a conservative state vying for the role of international leader in global right-wing politics. Retired NYU Professor Stephen F. Cohen’s recent writings, for example, have desperately tried to salvage a vision of post-Soviet Russia as somehow left-wing. While Cohen is not wrong to perceive continuity between Soviet and post-Soviet Russia, it is important to note that the relevant ideological continuity extends further back, with its origins lying in the messianic discourse of moral superiority associated with twentieth- and twenty-first century Russian intellectuals and, before them, with Russian Slavophilism, which intellectual historian Andrzej Walicki once described, quite accurately, as “a conservative utopia.”49 During the Soviet Union’s seven decades of existence, the conservative version of this Russian messianism persisted in the Russian diaspora and among Soviet dissidents such as Solzhenitsyn. The Soviet Union, meanwhile, projected its own purported moral superiority as the ostensible vanguard of socialism, a system understood as far more just than Western capitalism. Just as the official Soviet, left-wing version of this ideology of moral superiority attracted its share of fellow travelers, so has, and does, the now resurgent right-wing brand.

This right-wing iteration of moral exceptionalism entails a belief that Russia was given a Providential calling to revive the Christian roots of European, or more broadly Western, civilization. Despite (or perhaps because of) the sense of moral superiority of Russian civilization, it has proven irresistible to certain Western Russophiles—whether late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century British religious conservatives, or, fast forwarding to the present, American “paleo-conservative” Pat Buchanan.50 Notably, it was after Putin annexed Crimea on March 18, 2014, that Buchanan strongly suggested that God is on Russia’s side now.51 Like Buchanan, the American leadership in WCF seems prepared to see Russia as doing the Lord’s work, and therefore to go on working closely with Russian social conservatives despite tense international relations and concerns about Russia’s role in the Ukraine crisis.52 What’s more, Franklin Graham has lost all compunction about praising Putin, and, after a recent visit to Moscow during which he met with Patriarch Kirill, seems to be entirely on board with the idea that Russia is “protecting traditional Christianity.” In turn, Patriarch Kirill has declared American Protestants and Catholics who defend the “natural family” to be “confessors of the faith.” Such propagandistic statements, meant to impact U.S. public opinion, might be construed as Russia exporting its culture wars to us, as leaders of the “godless” West.53 In this regard, it is also worth noting that the Russian Orthodox Church, Moscow Patriarchate is expanding its presence in Paris, with plans for the construction of a new cathedral that will include a cultural center, which is expected to be completed by the end of this year.54 It is also important, of course, that Russia is exporting its culture wars in what the Russian state considers its more immediate sphere of influence, with Astakhov turning up at regional WCF conferences in countries such as Georgia, and а Russian-model anti-LGBTQ “propaganda” initiative, withdrawn at least for the present, having been recently considered in Kyrgyzstan’s parliament55

The events of 2014 may have tempered enthusiasm for Russia among some on the U.S. Right, but for many of those dedicated to the pursuit of an anti-human rights, “pro-family” agenda at home and abroad, partnership with Russian social conservatives will continue. If we wish to understand the effect of such partnerships, however, we must stop looking at Russian social conservatism as a kind of American import. We should take steps not to underestimate the global significance of Russian culture warring in its own right. While there is a complex transnational intellectual history at play here, Russian actors are more than capable of damaging LGBTQ and women’s rights all on their own, independent of U.S. actors. If we consider Russian involvement in WCF as entirely derivative of U.S. leadership, we may well miss the full import of the new Russia-led “right-wing international,” which would hamper the ability of human rights advocates to counter its influence.

Correction: An earlier version of this article mistakenly stated that Scott Lively is “on trial” for crimes against humanity. The legal proceedings against Mr. Lively have not yet reached the trial stage.

- Endnotes

1 Sergei Bulgakov, “Na vyborakh. Iz dnevnika” [Observing the Elections: From my Journal], Russkaia mysl’ [Russian Thought] 33:11 (1912), 185-92, esp. 189.

2 World Congress of Families IX, “The Family in Europe - Alexey Komov, Maria Hildingsson, Laszlo Marki, Dr. J. Szymcsak,” YouTube Video, 1:01:35, November 13, 2015, https://youtu.be/a9Rpyl2NofI.

3 I thank PRA researcher Cole Parke for providing me with a recording of Komov’s presentation, which he gave on October 27, 2015 to an apparently highly receptive audience (judging by the laughter, comments, and applause audible in the recording).

4 Benjamin May, “World Congress of Families IX Announces Four Recipients Who Will Receive Awards in Salt Lake City on October 27,” Christian Newswire, October 20, 2015, http://www.christiannewswire.com/news/7575776890.html.

5 Cole Parke, “U.S. Conservatives and Russian Anti-Gay Laws – The WCF.” Eyes Right Blog, October 17, 2013, https://www.politicalresearch.org/2013/10/17/u-s-conservatives-and-russian-anti-gay-laws-the-wcf/.

6 Rev. Kapya Kaoma, “Globalizing the Culture Wars: U.S. Conservatives, African Churches, and A form of heterosexism that devalues and scapegoats gay, lesbian, and bisexual people and people in same-gender relationships. Learn more ,” Political Research Associates: 2009, https://www.politicalresearch.org/2009/12/01/globalizing-the-culture-wars-u-s-conservatives-african-churches-homophobia/.

7 For example, see Xenia Loutchenko, “Vera ili ideologiia? ‘Tsargrad-TV’, Radio ‘Vera,’ i Novye Dukhovnye Skrepy” (Faith or Ideology? Tsargrad-TV, Radio ‘Faith,’ and New Spiritual Supports), Colta, September 22, 2014, http://m.colta.ru/articles/media/4720.

8 My abridged translation of our interview has been published in a new independent U.S.-based journal of Orthodox Christian thought. “Religion and Politics in Russia: An Insider’s View. Xenia Loutchenko Interviewed by Chrissy Stroop,” The Wheel 1:3 (2015), 30-35, Available online: http://static1.squarespace.com/static/54d0df1ee4b036ef1e44b144/t/564281e0e4b0a83ded1ed25e/1447199200469/Loutchenko.pdf.

9 Ibid.

10 Hannah Levintova, “How US Evangelicals Helped Create Russia’s Anti-Gay Movement,” Mother Jones, February 21, 2014. http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2014/02/world-congress-families-russia-gay-rights.

11Cole Parke, “U.S. Conservatives and Russian Anti-Gay Laws – The WCF.” Eyes Right Blog, October 17, 2013, https://www.politicalresearch.org/2013/10/17/u-s-conservatives-and-russian-anti-gay-laws-the-wcf/.

12 Chrissy Stroop, “Nationalist War Commentary as Russia’s Religious Thought: The Religious Intelligentsia’s Politics of Providentialism.” Russian Review 72:1 (2013), 94-115, esp. 100-01.

13 E. N. Trubetskoi, “Vozvrashchenie k filosofii” (The Return to Philosophy) in Filosofskii sbornik L’vu Mikhailovichu Lopatinu k tridtsatiletiiu nauchno-pedagogicheskoi deiatel’nosti. Ot Moskovskago Psikhologicheskogo Obshchestva. 1881-1911.) (Philosophical Festschrift in Honor of Lev Mikhailovich Lopatin’s Thirty Years of Scientific-Pedagogical Work [1881-1911], from the Moscow Psychological Society). (Moscow: Kushnerev, 1912), 1-9, esp. 9.

14 T. S. Eliot, The Idea of a Christian Society, NY: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1940.

15 Catherine Baird, “Religious Communism? Nicolai Berdyaev’s Contribution to Esprit’s “Interpretation of Communism,” Canadian Journal of History 30:1 (1995), 29-47.

16 Chrissy Stroop, “The Russian Origins of the So-Called Post-Secular Moment: Some Preliminary Observations,” State, Religion and Church 1:1 (2014), 59-82, https://www.academia.edu/5949640/The_Russian_Origins_of_the_So-Called_Post-Secular_Moment_Some_Preliminary_Observations.

17 Scott Kaufman, “Fox Guest: Keep The act of favoring members of one community/social identity over another, impacting health, prosperity, and political participation. Learn more Legal Because Bible Tells Businesses Not to Hire Atheists,” Alternet, April 7, 2015. http://www.alternet.org/news-amp-politics/fox-guest-keep-discrimination-legal-because-bible-tells-businesses-not-hire.

18 Chrissy Stroop, “The Russian Origins of the So-Called Post-Secular Moment: Some Preliminary Observations,” State, Religion and Church 1:1 (2014), 59-82, https://www.academia.edu/5949640/The_Russian_Origins_of_the_So-Called_Post-Secular_Moment_Some_Preliminary_Observations.

19 Kathryn Joyce, “Missing: The ‘Right’ Babies,” The Nation, February 14, 2008, http://www.thenation.com/article/missing-right-babies/.

20 Although it is a little too essentializing in its treatment of Russian national character, on Russian exceptionalism, including brief comments on Dugin, see Paul Coyer, “(Un)Holy Alliance: Vladimir Putin, the Russian Orthodox Church and Russian Exceptionalism,” Forbes, May 21, 2015, http://www.forbes.com/sites/paulcoyer/2015/05/21/unholy-alliance-vladimir-putin-and-the-russian-orthodox-church/.

21 Anton Barbashin and Hannah Thoburn, “Putin’s Brain: Alexander Dugin and the Philosophy Behind Putin’s Invasion of Crimea. Foreign Affairs, March 31, 2014, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russia-fsu/2014-03-31/putins-brain.

22 Paul Goble, “Window on Eurasia: The Kremlin’s Disturbing Reading List for Russia’s Political Elite,” Window on Eurasia—New Series, January 24, 2104, http://windowoneurasia2.blogspot.ru/2014/01/window-on-eurasia-kremlins-disturbing.html.

23 Joshua Keating, “God’s Oligarch,” Slate, October 20, 2014, http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/foreigners/2014/10/konstantin_malofeev

_one_of_vladimir_putin_s_favorite_businessmen_wants_to.html.24 Xenia Loutchenko, “Vera ili ideologiia? ‘Tsargrad-TV’, Radio ‘Vera,’ i Novye Dukhovnye Skrepy” (Faith or Ideology? Tsargrad-TV, Radio ‘Faith,’ and New Spiritual Supports), Colta, September 22, 2014, http://m.colta.ru/articles/media/4720.

25 Miranda Blue, “Pussy Riot’s American Detractors,” Right Wing Watch, February 18, 2014, http://www.rightwingwatch.org/content/pussy-riots-american-detractors.

26 Alexander Morozov, “Konservativnaia revoliutsiia: smysl Kryma” [A Conservative Revolution: The Meaning of Crimea], Colta, March 17, 2014, http://www.colta.ru/articles/society/2477.

27 Brody Levesque, “Russian children’s rights commissioner: only Italy can adopt Russian children,” LGBTQ Nation, December 3, 2013, http://www.lgbtqnation.com/2013/12/russian-childrens-rights-commissioner-only-italy-can-adopt-russian-children/.

28 See Miranda Blue, “Globalizing Homophobia, Part 2: ‘Today the Whole World is Looking at Russia,’” Right Wing Watch, October 3, 2013. http://www.rightwingwatch.org/content/globalizing-homophobia-part-2-today-whole-world-looking-russia.

29 “Federal Law of the Russian Federation of July 29, 2013, No. 135-F3, Moscow. Amending Article 5 of the Federal Law ‘On the Defense of Children from Information Harmful for their Health and Development,’ and other legislative acts of the Russian Federation with the goal of protecting children from propaganda rejecting traditional family values.”: http://www.rg.ru/2013/06/30/deti-site-dok.html

30 Alexander Morozov, “Konservativnaia revoliutsiia: smysl Kryma” [A Conservative Revolution: The Meaning of Crimea], Colta, March 17, 2014. http://www.colta.ru/articles/society/2477.

31 Jennifer Monaghan, “Russian Orthodox Priest: Parental Violence Campaigns are Anti-Family,” The Moscow Times, March 24, 2015. http://www.themoscowtimes.com/article/russian-orthodox-priest-parental-violence-campaigns-are-anti-family/517976.html. Archpriest Dimitry Smirnov, “Vystuplenie protoiereia Dimitriia Smirnova na Obshchesetvennom sovete P. Astakhova” (Archpriest Dimitry Smirnov’s Presentation at the Community Forum of [the Ombudsman of the Office of the President of the Russian Federation for Children’s Rights] P. Astakhov). April 5, 2014. http://www.dimitrysmirnov.ru/blog/cerkov-56880/.

32 With respect to abortion, as of November 21, 2011, according to Federal Law 323-F3, Russia banned abortions after 12 weeks except in the case of rape (up to 22 weeks) or medical necessity (at any time). Orthodox Christian leaders and their allies in the Duma continue to push for more severe restrictions, such as required ultrasounds.

33 Sergei Chapnin, “A Church of Empire: Why the Russian Church Chose to Bless Empire,” First Things, November 2015, http://www.firstthings.com/article/2015/11/a-church-of-empire. Chapnin served as managing editor of the Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate, an official organ of the Russian Orthodox Church, Moscow Patriarchate, from 2009 until December 16, 2015. Chapnin’s moderate, highly informed and frank assessments of Russian church life are impressive, and his presence in the patriarchate was a rare bright spot among its prominent predominantly Generically used to describe factions of right-wing politics that are outside of and often critical of traditional conservatism. Learn more voices. On December 18, social media associated with the Russian intelligentsia and Orthodox Church exploded with the news that Chapnin had been fired from the patriarchate for his critical views of the church’s prevailing ideology and relationship to the Russian state, particularly for remarks he made in a talk given at the Carnegie Moscow Center on December 9. The media have now confirmed the firing. See, for example, “Moscow Patriarchate Fires Sergey Chapnin, Editor of its Journal.” AsiaNews.it, Dec. 19, 2015. http://www.asianews.it/news-en/Moscow-Patriarchate-fires-Sergey-Chapnin,-editor-of-its-journal-36205.html.

34 Franklin Graham, “Putin’s Olympic Controversy,” Decision Magazine, February 28, 2014, http://billygraham.org/decision-magazine/march-2014/putins-olympic-controversy/.

35 Hannah Levintova, “How US Evangelicals Helped Create Russia’s Anti-Gay Movement,” Mother Jones, February 21, 2014. http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2014/02/world-congress-families-russia-gay-rights. Meredith Bennett-Smith, “Scott Lively, American Pastor, Takes Credit for Inspiring Russian Anti-Gay Laws,” Huffington Post, September 9, 2013, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/09/19/scott-lively-russian-anti-gay-laws_n_3952053.html.

36 Quoted in Jay Michaelson, “The ‘Natural Family’: The Latest Weapon in the Christian Right’s New Global War on Gays,” The Daily Beast, June 14, 2015, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/06/14/the-natural-family-the-latest-weapon-in-the-christian-right-s-new-global-war-on-gays.html.

37 Chrissy Stroop, “Russian Parliament Hosts U.S. Anti-Gay Activist Paul Cameron,” Religion Dispatches, December 12, 2013. http://religiondispatches.org/russian-parliament-hosts-u-s-anti-gay-activist-paul-cameron/.

38 World Congress of Families, “Planning for World Congress of Families VIII Suspended,” n.d., http://worldcongress.org/press-releases/planning-world-congress-families-viii-suspended.

39 Evan Hurst, “Russian ‘Pro-Family’ Conference Exposing Internal Dissension Among American Religious Right Leaders?” Two Care Center Against Religious Extremism, September 10, 2014, http://www.twocare.org/russian-pro-family-conference-exposing-internal-dissension-among-american-religious-right-leaders/.

40 Mykhailo Cherenkov, “Orthodox Terrorism,” First Things, May 2015, http://www.firstthings.com/article/2015/05/orthodox-terrorism.

41 Philip Jenkins, “Putin’s Corrupted Orthodoxy,” The American Conservative, March 24, 2015, http://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/putins-corrupted-orthodoxy/.

42 Hannah Levintova, “Did Anti-Gay Evangelicals Skirt US Sanctions on Russia?” Mother Jones, September 8, 2014, http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2014/09/world-congress-families-russia-conference-sanctions.

43 Peter Montgomery, “World Congress of Families in Denial over Promoting Homophobia Globally,” Right Wing Watch, October 21, 2015, http://www.rightwingwatch.org/content/world-congress-families-denial-over-promoting-homophobia-globally.

44 “Final Plenary Session,” International Forum “Large Family [sic.] and the Future of Humanity,” http://www.familyforum2014.org/#!final-plenary-session/c1umu.

45 “Resolutions and Voting Results of 29th HRC Session,” UN Watch, July 2, 2015, http://www.unwatch.org/resolutions-and-voting-results-of-29th-hrc-session/.

46 Jay Michaelson, “At the United Nations, it’s Human Rights, Putin Style,” The Daily Beast, June 26, 2014, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/06/26/at-the-united-nations-it-s-human-rights-putin-style.html. Rebecca Oas, “Big Win for Traditional Family at UN Human Rights Council,” C-Fam, July 9, 2015, https://c-fam.org/friday_fax/big-win-for-traditional-family-at-un-human-rights-council/.

47 “Plod very. Posol vsemirnogo kongressa semei v OON Alexey Komov. Chast’ 2” (The Fruits of Faith. The Ambassador of the World Congress of Families to the UN, Alexey Komov. Part 2), http://tv-soyuz.ru/peredachi/plod-very-posol-vsemirnogo-kongressa-semey-v-oon-aleksey-komov-chast-2.

48 On the National Front’s relationship to Russia see Anne-Claude Martin, “National Fronts Russian Loans Cause Uproar in European Parliament,” EurActiv.com, December 5, 2014, http://www.euractiv.com/sections/europes-east/national-fronts-russian-loans-cause-uproar-european-parliament-310599. Also relevant: Sam Ball, “Sarkozy to Meet Putin as French Right Looks to Russia,” France 24, October 29, 2015, http://www.france24.com/en/20151028-sarkozy-meet-putin-french-right-looks-russia-syria-hollande-assad.

49 Andrzej Walicki, The Slavophile Controversy: History of a Conservative Utopia in Nineteenth-Century Russian Thought, Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1989.

50 Michael Hughes, “The English Slavophile: J. W. Birkbeck and Russia,” The Slavonic and East European Review, 82:3 (2004), 680-706.

51 Patrick J. Buchanan, “Whose Side is God on Now?” April 4, 2014. http://buchanan.org/blog/whose-side-god-now-6337.

52 For more evidence of this, note the effusive praise lavished on Russian actors by WCF IX Executive Director Janice Shaw Crouse: Fr. Mark Hodges, “Janice Shaw Crouse: Homosexual Activists Peddling ‘Falsehoods’ about World Congress of Families,” Life Site, September 29, 2015, https://www.lifesitenews.com/news/janice-shaw-crouse-homosexual-activists-peddling-falsehoods-about-world-con.

53 “Franklin Graham praises ‘Gay Propaganda’ Law, Criticizes US ‘Secularism,’ in Russia Visit,” Pravmir, November 3, 2015, http://www.pravmir.com/franklin-graham-praises-gay-propaganda-law-critizes-us-secularism-in-russia-visit/. Priest Mark Hodges, “Russian Orthodox Patriarch: Americans for natural marriage are ‘Confessors of the Faith,’” Pravmir, November 3, 2015, http://www.pravmir.com/russian-orthodox-patriarch-americans-for-natural-marriage-are-confessors-of-the-faith/.

54 “France: A New Russian Orthodox Cathedral in Paris,” Dici, February 14, 2014, http://www.dici.org/en/news/france-a-new-russian-orthodox-cathedral-in-paris/. “Frantsiia razreshila stroit’ pravoslavnyi dukhovno-kultur’nyi tsentr v parizhe” (France has Permitted the Construction of an Orthodox Cultural Center in Paris), Pravoslavie.ru, December 25, 2013, http://www.pravoslavie.ru/news/67006.htm. Since the days of Berdyaev and Bulgakov, both of whom lived out most of the rest of their lives in France after the Bolshevik victory in the Russian civil war, there has been a large Russian Christian presence in Paris with a complicated relationship to Moscow. While the details of this situation are beyond the scope of this article, it is important to note that Moscow seems to be attempting to exert greater influence over the ethnic Russian Christian population that remains in France.

55 “Pavel Astakhov prinial uchastie v konferentsii Vsemirnogo kongressa semei v Tbilisi” (Pavel Astakhov Took Part in a Conference of the World Congress of Families in Tbilisi), Press Service of the President of the Russian Federation’s Ombudsman for Children’s Rights, May 18, 2015, http://www.rfdeti.ru/news/9835-pavel-astahov-prinimaet-uchastie-v-konferencii-vsemirnogo-kongressa-semey-v-tbilisi. “ V Kyrgyzstane iz parlamenta otozvan zakonoproekt o zaprete gei-propagandy” (In Kyrgyzstan the Parliamentary Bill Banning Gay Propaganda has been Withdrawn), Gay Russia, June 30, 2015, http://www.gayrussia.eu/world/11571/.