The Origins of Black Conservatism

In order to understand Black conservatism, it is important to understand the character of the Black bourgeoisie. Developing as it did within the context of white cultural The use of violence, intimidation, surveillance, and discrimination, particularly by the state and/or its civilian allies, to control populations or particular sections of a population. Learn more , it is not surprising that the values identified by Black conservative intellectuals such as Shelby Steele and Thomas Sowell as “traditional American values” are hallmarks of both American conservative mythology and Black bourgeois mythology. The ethic of “individual initiative” and “strong families” are values intimately related to the stereotypes that locate Black poverty in the misbehavior of those Blacks who do not make progress.

Black bourgeois mythology is a powerful theme in the African American community, one that exists on two layers. First, like the conservative Horatio Alger myth, Black bourgeois mythology asserts that values and behavior determine economic success. Second, the myth maintains that middle class African Americans are different from other African Americans. The development of the Black bourgeoisie is rooted in its apartness from the Black mass majority.

Prior to desegregation, African Americans of all socioeconomic groups lived in the same segregated communities. The economic and political position of the Black bourgeoisie depended on the business and political support of poorer Blacks living under segregated circumstances. Nonetheless, most of the Black bourgeoisie historically has seen itself (even when white America has not) as different from the Black masses, in attitude and behavior as well as in economic success.

“The ethic of ‘individual initiative’ and ‘strong families’ are values intimately related to the stereotypes that locate Black poverty in the misbehavior of those Blacks who do not make progress.”

Histories of the socio-cultural development of the Black middle class emphasize the pivotal role played by schooling for newly freed slaves, schooling which often would make them members of an incipient Black bourgeoisie in the immediate post-Civil War era. Initially, most of this schooling was carried out by white missionaries and abolitionists from the north, and later by Black graduates of their schools. These white instructors were intent on imparting the Puritan work ethic and morality prevalent in white schools of the day. Thus, among other things, the schooling emphasized “proper” sexual behavior. Schools demanded that students be chaste, especially the girls, and all students were expected to marry and live “conventional” family lives.

The emphasis on “moral” sexual behavior had special significance in the case of Black students. White northern teachers emphasized it because, using paternalistic and implicitly racist reasoning, they believed it the best way to disprove Southern white racists’ belief that the “Negro’s savage instincts” prevented him from conforming to puritanical sex behavior.

“Moral” sexual behavior resonated with newly-freed slaves for a number of reasons—among them, the sexual exploitation and denial of the right to family life under slavery, and the teachings of the Black Church.

“Histories of the socio-cultural development of the Black middle class emphasize the pivotal role played by schooling for newly freed slaves, schooling which often would make them members of an incipient Black bourgeoisie in the immediate post-Civil War era.”

In addition to insisting on high moral standards, schooling for the incipient Black middle class added the classist and racist concept that only “common Negroes” engaged in “unconventional” sexual behavior and a wide array of other “dysfunctional,” “primitive” behaviors, such as laziness, boisterousness, improvidence, and drunkenness. Thus, it was their values and their behaviors that made Black elites elite and set them apart from the Black masses.

It is no accident that today both liberal and conservative Black elites are preoccupied by what is, in reality, a nonexistent “epidemic” of Black teen pregnancies, or that poor, female-headed households receive special opprobrium. In part, this stems from the overall patriarchal character of U.S. culture—one in which white ethnic groups’ poverty is also largely blamed on female-headed households. But sexual behavior has long been a touchstone of Blacks’ civilized status.

Indeed, it is important to recognize that a historical strain in Black political agitation was that elite Blacks were being denied the rights they deserved by virtue of having proved themselves “civilized”, i.e. better than and separate from “ ‘common Negroes.” In the words of Adolph Reed, Jr: “Race spokespersons commonly have included in their briefs against segregation (or

The act of favoring members of one community/social identity over another, impacting health, prosperity, and political participation.

Learn more

in other forms) an objection that its purely racial character fails to differentiate among blacks and lumps the respectable, cultivated, and genteel in with the rabble.”

“ ‘Moral’ sexual behavior resonated with newly-freed slaves for a number of reasons—among them, the sexual exploitation and denial of the right to family life under slavery, and the teachings of the Black Church.”

I emphasize this because far too little attention has been paid to the extent to which Black conservatives’ arguments—whether delineating the causes of Black oppression, locating the causes of Black poverty, or (as will be seen) making the case against affirmative action—all come back to issues of distinguishing middle class from poor Blacks. This holds also for Black conservatives as individuals, and their need to distinguish themselves, their status, and their identity from negative Black stereotypes.

The Role of Internalized Oppression

Apart from their classic Black bourgeois perspectives, Black conservative intellectuals also consistently demonstrate they have personally internalized negative stereotypes about poor African Americans and about African American culture. The evidence for this lies in the underlying assumptions of their written work, the descriptions of poor African Americans in that work, and their personal biographies.

In 1986 Glenn Loury wrote: “But it is now beyond dispute that many of the problems of contemporary black American life lie outside the reach of effective government actions and these can only be undertaken by the black community itself. These problems involve at their core the values, attitudes, and behaviors of individual blacks. They are exemplified by the staggering statistics on pregnancies among young, unwed black women and the arrest and incarceration rates among black men.”

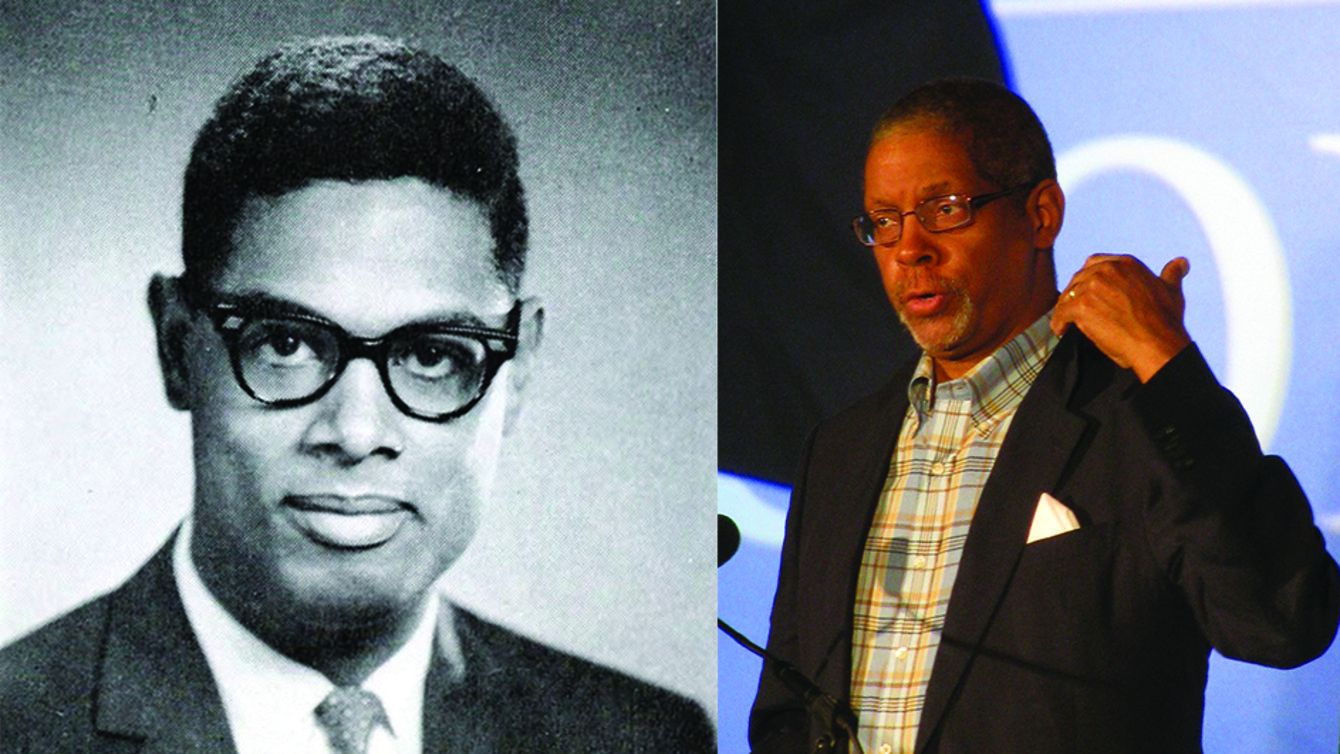

Yet Loury’s personal history includes fathering two out-of-wedlock children, a jailing for non-payment of child support, and 1987 arrests for cocaine and marijuana possession and for assaulting the young mistress he had established in a separate household. Referring to that past history Loury has said: “I thought if I hung out in the community and engaged in certain kinds of social activities, in a way I was really being black.”

“Far too little attention has been paid to the extent to which Black conservatives’ arguments…all come back to issues of distinguishing middle class from poor Blacks.”

English professor Shelby Steele complains that African Americans suffer from a collective self-image that prefers victimization to success and imposes a suffocating racial conformity that ostracizes nonconformists like him. He discusses his own dissociation from images of lower-class Black life when it was represented by an imaginary character named Sam, created by his childhood family. Sam embodied all the negative images of Blacks his father had left behind because “they were ‘going nowhere.’”

Steele succinctly states his concern about being confused with poor Blacks when he admits: “The stereotype of the lazy black SOB is common, and the fear is profound that I’ll be judged by that stereotype. They will judge our race by him [an unemployed young Black man]—and they’ll overlook me, quietly sitting on that bus grading those papers.”

Nowhere in the array of Black conservatives’ positions are the themes of traditional Black bourgeois attitudes and personal individual status and identity more prevalent than in Black conservatives’ opposition to affirmative action. As we have seen earlier, in their analyses of Black oppression and the Black culture of poverty the foundation of their arguments comes from white conservatives and neoconservatives.

“Nowhere in the array of Black conservatives’ positions are the themes of traditional Black bourgeois attitudes and personal individual status and identity more prevalent than in Black conservatives’ opposition to affirmative action.”

Black Conservatives and Affirmative Action

Nathan Glazer’s 1975 book, Affirmative Action, Ethnic Inequality and Public Policy, summarized white neoconservatives’ objections to affirmative action: that by the end of the 1960s, discrimination was no longer a major obstacle to minorities’ access to employment, education and other social mobility mechanisms; affirmative action has not benefited the poor who need it most, but has primarily benefited middle-class Blacks and other minorities; and affirmative action fuels white resentment against minorities.

In his 1984 book, Civil Rights: Rhetoric or Reality?, Thomas Sowell repeats each of Glazer’s basic objections. Quoting statistics from the Moynihan Report, Sowell insists: “The number of blacks in professional, technical, and other high level occupations more than doubled in the decade preceding the Civil Rights Act of 1964…. The trend was already under way.” Also, like Glazer and other white conservatives, Sowell maintains that: “The relative position of disadvantaged individuals within the groups singled out for preferential treatment has generally declined under affirmative action.”

Sowell and the other Black conservatives insist affirmative action programs violate whites’ “constitutional rights” in general and those of white males in particular. Not only is this seen as unfair, but, like Glazer, Black conservatives worry about the resulting white resentment. In Sowell’s words: “There is much reason to fear the harm that it is currently doing to its supposed beneficiaries, and still more reason to fear the long-run consequences of polarizing the nation…. Already there are signs of hate organizations growing in more parts of the country and among more educated classes than ever took them seriously before.”

“It is this self-esteem component that reflects the personal status concerns of Sowell and other Black conservatives.”

What is most interesting about Sowell’s affirmative action critique, however, is not that he repeats the standard white conservative critique, but that he adds a self-esteem component to that critique. It is this self-esteem component that reflects the personal status concerns of Sowell and other Black conservatives.

Sowell argues that while accomplishing few positive results, affirmative action actually undermines the efforts of successful minority individuals by creating a climate in which it will be assumed that their achievements reflect not individual worth, talent, or skill, but special consideration. “Pride of achievement is also undermined by the civil rights vision that assumes credit for minority and female advancement. This makes minority and female achievement suspect in their own eyes and in the eyes of the larger society.”

Other Black conservative intellectuals follow Sowell’s position, first making the same criticisms as white conservatives but adding self-esteem, personal diminishment, and status issues. Shelby Steele complains that affirmative action has reinforced a self-defeating sense of victimization among Blacks by encouraging us to blame our failures on white An ideology that assumes a hierarchy of human worth based on the social construction of racial difference. Racism as an ideology claims superiority of the socially constructed category, White, over other racialized categories based on the false idea that race is a fixed and immutable reality. Learn more rather than on our own shortcomings. He too worries that affirmative action “makes automatic a perception of enhanced competence for the unpreferreds and of questionable competence for the preferreds—the former earned his way…while the latter made it by color as much as by competence.”

“Sowell argues that while accomplishing few positive results, affirmative action undermines the efforts of successful minority individuals by creating a climate where it’s assumed that their achievements reflect not individual worth, talent, or skill, but special consideration.”

In Reflections of an Affirmative Action Baby, Stephen Carter denies being a conservative. But his discussion of affirmative action is a mirror image of the standard neoconservative critique. Like Glazer, Carter argues that: “What has happened in America in the era of affirmative action is this: middle-class black people are better off and lower class black people are worse off.” Carter’s “best black syndrome” is the most quoted Black conservative status/self-esteem statement about affirmative action: “The best black syndrome creates in those of us who have benefited from racial preferences a peculiar contradiction. We are told over and over that we are the best black people in our profession. And we are flattered…. But to professionals who have worked hard to succeed, flattery of this kind carries an unsubtle insult, for we yearn to be called what our achievements often deserve; simply the best—no qualifiers needed!”

Carter and the other Black conservative intellectuals say they object to the fact that affirmative action benefits those minorities who are already middle income. They do not produce convincing statistical evidence to support this contention. Nor do they recognize that affirmative action was designed to address discrimination, not economic disadvantage, or that most government programs benefit middle and, especially, high income groups. Nor do Black conservatives ever recommend that affirmative action become a program for all poor people, including the more than ten million poor whites in this country.

What Black conservatives do argue for is that Blacks compete on merit and merit alone. Their “merit only” policy is clearly an idealized paradigm. It ignores the fundamental reality that any selection process is always a combination of some imperfect assessment of merit (skills and talent) and purely personal filtering processes. To assume that race and/or gender considerations are neutral at the level of personal filtering is naive to say the least.

“Nor do Black conservatives ever recommend that affirmative action become a program for all poor people, including the more than ten million poor whites in this country.”

What is clear in Black conservatives’ defense of merit as the sole criterion for selection or advancement is their own sense of personal diminishment by affirmative action labels. Indeed, Black conservatives fret a great deal about proof of their personal talent. And their comments, focused as they are on white’s judgments of them and their capabilities, demonstrate that, ironically, they remain very much the captives of white racism.

A genuinely confident African American does not care if whites see her/him as the beneficiary of affirmative action imperatives, knowing that racism ipso facto dictates that success on the part of Blacks be seen as the result of unfavorable advantages. Thomas Sowell adamantly denies ever having been an affirmative action beneficiary and reportedly resents being identified as a “Black” anything.

Glenn Loury blasted white liberal Hendrik Hertzberg for saying he’d never met a well-informed, unbigoted Black who did not agree we have to be twice as talented and twice as hardworking to achieve the same degree of success as our white counterparts: “How quickly he [Hertzberg] forgets! We’ve met more than once, and in the course of our encounters never did I confirm, and often did I contradict the sentiments he ascribes to all ‘well informed, unbigoted’ blacks. I can only conclude that my earnest denunciation of affirmative action failed to register as the legitimate sentiments of a black intellectual…. Perhaps he simply dismissed my opinions as a shockingly familiar

A variant of ideological conservatism combining features of traditional conservatism with political individualism and a qualified endorsement of free markets.

Learn more

in blackface.”

“To assume that race and/or gender considerations are neutral at the level of personal filtering is naive to say the least.”

Given that Black conservatives associate negative racial attributes with low income Blacks, it is not surprising that much of Black conservative analysis seeks to distinguish middle class from lower class Blacks. An unstated but clear objective throughout Black conservatives’ arguments is the attempt to recast the current American identification of “Black” with (in Steele’s words) “the least among us” to one in which “Black” is identified with their positive stereotype of middle class Blacks.

Glenn Loury captures this point: “The fact that the values, social norms, and social behaviors often observed among the poorest members of the black community are quite distinct from those characteristic of the black middle class indicates a growing divergence in the social and economic experiences of black Americans.” Loury produces no supporting evidence for this observation.

The Time of Self-Help

Black conservative intellectuals’ solutions for improving race relations are very much tied to the classic attitudes of the Black bourgeoisie, and to issues of identity and status. Further, their solutions always assign leadership roles to the Black middle class. Consistent with their analysis of the causes of Black oppression and Black poverty, they return to the “slavery damaged” theme, and locate the solutions within individual Blacks and the Black community. The reasoning behind their proposed solutions represents some of the most reactionary of their thinking.

“Black conservative intellectuals’ solutions for improving race relations are very much tied to the classic attitudes of the Black bourgeoisie, and to issues of identity and status.”

Loury and the other Black conservatives insist “self help” is the only viable solution to Black dilemmas. They argue we have to rely on ourselves because, as Loury states referring to Booker T. Washington, “[Washington] understood that when the effect of past oppression has been to leave people in a diminished state, the attainment of true equality with their former oppressor cannot much depend on his generosity but must ultimately derive from an elevation of their selves above the state of diminishment.”

In addition, Loury and others have developed the profoundly subversive notion, as described by Adolph Reed, that “it is somehow illegitimate for black citizens to view government action and public policy as vehicles for egalitarian redress.” Unlike all other American citizens, African Americans, according to Black conservatives, must win white approval by proving ourselves worthy of the rights of citizenship.

“The progress that must now be sought is that of achieving respect, the equality of standing in the eyes of one’s political peers, of worthiness as subjects of national concern,” Loury argues. Loury frequently acknowledges his intellectual debt to Booker T. Washington’s controversial philosophy. He concedes Washington’s approach may not have been entirely appropriate for the political and social contexts of his time, but Loury firmly believes the Washington approach is relevant in the post-civil rights era. “The point on which Booker T. Washington was clear, and his critics seem not to be, is that progress of the kind described above must be earned, it cannot be demanded.”

“Self-help literally defines how African Americans have managed to survive slavery, Reconstruction, and a series of trials and travails right up through the present day.”

Consistent with their belief in the superiority of the Black middle class, Black conservatives argue that instead of relying on government programs and civil rights legislation, middle class Blacks should make economic investments in Black communities, Blacks should support Black businesses, and most important, the Black middle class needs to teach poor African Americans proper behavior and values. This self-help language, cloaked as it is in Black cultural nationalist rhetoric, has been among the most warmly received of the Black conservative messages in the African American community.

This is not surprising. First of all, self-help literally defines how African Americans have managed to survive slavery, Reconstruction, and a series of trials and travails right up through the present day. Black conservatives and those praising them on this point sound as though African American history has not always included such famous proponents and practitioners of self-help as Martin Delaney, Edward Blyden and Alexander Crummel, Marcus Garvey, the Nation of lslam, the Black Panthers, Jesse Jackson’s Operation PUSH, and the thousands of Black women’s clubs, Black Greek and professional associations and Black church-based organizations, among others. But African Americans’ long heritage of self-help activities has tended to see self-help as a supplement to, not a replacement for, deserved government services and full employment at family-sustaining wages.

In addition to its historical resonance for African Americans, the Black conservative promotion of self-help flatters the Black middle class, casting it as the salvation for poor African Americans. It is noteworthy that even some liberal and progressive middle class Blacks have endorsed the Black conservatives’ “culture of poverty” analysis and their call for self-help to address the problem.

“It is noteworthy that even some liberal and progressive middle class Blacks have endorsed the Black conservatives’ ‘culture of poverty’ analysis and their call for self-help to address the problem.”

What is missed about Black conservatives’ self-help advocacy is that, unlike the cultural Black nationalist tradition whose rhetoric they borrow, theirs is neither an organic, collective model of self-help, nor one intended to enhance Black unity and Black cultural integrity. It is based on a savage individualism, advocating a laissez-faire formula for Black progress through the commitment of individual Blacks to economic wealth and cultural assimilation.

As stated by Shelby Steele: “The middle class values by which we [the Black middle class] were raised—the work ethic, the importance of education, the value of property ownership, of respectability, of ‘getting ahead,’ of stable family life, of initiative, of self reliance, et.cetera—are, in themselves, raceless and even assimilationist. They urge us toward participation in the American mainstream, toward integration, toward a strong identification with the society, and toward the entire constellation of qualities that are implied in the word individualism.”

Steele’s comments illustrate another subversive aspect of Black conservatives’ proposed solutions—the call to subsume our racial identity and to forgo collective racial action in favor of individualistic pursuits and a nationalistic American identity. Black conservatives issued this call during the 1980’s, at a time when overt racist (and frequently violent) attacks on Blacks were at a post-civil rights era high, when the national political leadership of the country implicitly signaled its approval of racist attitudes, and when government and corporate policies were decimating poor and middle class African Americans alike with last hired/first fired policies. Given the political climate of the 1980’s, Black conservatives were calling for no less than Black acquiescence and appeasement in their own oppression.

“Indeed Black conservatives’ highest visibility is in the white, not the Black community.”

Black Conservatives’ Ties to White Conservatives

Black conservatives are few in number, with few exceptions have no name recognition in the African American community, have little to no institutional base in our community, have no significant Black following, and no Black constituency. Indeed Black conservatives’ highest visibility is in the white, not the Black community. It is due primarily to their tics to white conservative institutions that Black conservatives have come to be viewed as spokespersons for the race, despite lacking a base in the African American community. Conservative think tanks such as the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace, the American Enterprise Institute and the Heritage Foundation (which has even implemented a minority outreach program), and conservative foundations such as the Olin Foundation, the Scaife Foundation, and the Bradley Foundation sponsor Black conservatives in numerous ways.

White conservative institutions award Black conservatives fellowships, consultant work, directorships, and staff positions. They also provide public relations services which get Black conservatives television and radio appearances, help get editorials, opinion pieces, and articles by Black conservatives into mainstream, even liberal, newspapers and magazines, publish articles and books by Black conservatives, and sponsor workshops and conferences by and for Black conservatives.

Conservative and neoconservative publications such as The Wall Street Journal, Human Events, The Washington Times, Commentary, The Public Interest, The National Interest, American Scholar, and The New Republic have played a major role in promoting Black conservatives’ visibility, publishing articles by and about them. And finally, the Republican Party, especially during the years of the Reagan Administration but also during the Bush Administration, rewarded Black conservatives with high-visibility government appointments and with financing for Black conservative electoral campaigns.

“A review of prominent Black conservatives’ careers reveals the extent to which they have benefited from their corporately-funded presence in white conservative foundations, think tanks, and publications.”

The Institute of Contemporary Studies, a conservative research organization established by former aides to Ronald Reagan after Reagan left the statehouse in Sacramento, sponsored the first conference of Black neoconservatives in San Francisco in December, 1980. Called The Fairmont Conference, it attracted about 125 conservative Black lawyers, physicians, dentists, ivy league professors, and commentators. It remains the best-known gathering of Black conservative thinkers and policy makers.

A review of prominent Black conservatives’ careers reveals the extent to which they have benefited from their corporately-funded presence in white conservative foundations, think tanks, and publications.

Thomas Sowell is a senior fellow at the conservative Palo Alto think tank, The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace. Sowell is the most prolific of the Black conservative intellectuals; his fourteen books have been widely reviewed in conservative and mainstream publications alike. Conservative publications such as Commentary, The American Spectator, Human Events, The Wall Street Journal, Barron’s, and Businessweek consistently provide the most glowing reviews. Articles by and/or about Sowell have appeared in numerous mainstream publications such as Time, Newsweek, The Washington Post, and The New York Times, among others.

When Sowell decided in 1981 to start a (short-lived) organization explicitly intended to counter the NAACP, the Black Alternatives Association, Inc., he reportedly received immediate pledges totaling $1,000,000 from conservative foundations and corporations.

Glenn Loury’s reputation and influence rest on only one book and a series of articles that have appeared in most of the major mainstream publications, as well as the conservative Wall Street Journal, Commentary, and The Public Interest. The Heritage Foundation published one of his best known essays, “Who Speaks for American Blacks,” as a monograph in A Conservative Agenda for America’s Blacks. Boston University’s rightist President John Silber hired Loury when Loury left Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government.

Robert Woodson has served in several capacities at the American Enterprise Institute. Woodson is also an adviser for the Madison Group, a loose affiliation of conservative state-level think tanks, launched in 1986 by the American Legislative Exchange Council or ALEC. ALEC is an association of approximately 2,400 conservative state legislators and is housed in the Heritage Foundation’s headquarters in Washington, D.C. The conservative John M. Olin Foundation gave $25,000 to Woodson’s National Center for Neighborhood Enterprise. Woodson’s 1987 book, Breaking the Poverty Cycle: Private Sector Alternatives to the Welfare State, was published by the conservative National Center for Policy Analysis in Dallas, then reissued in 1989 by the conservative Commonwealth Foundation, on whose board he sits.

“It is important to question the implications of the fact that Black conservatives’ arguments originate in white conservatives’ arguments, and that Black conservatives are in no way answerable to a Black constituency.”

Walter Williams is the John M. Olin Distinguished Professor of Economics at George Mason University, has been a fellow at the Hoover Institution and at the Heritage Foundation, and received funding for one of his books from the Scaife Foundation.

The importance of these ties is not white conservative patronage per se. Black liberals benefit from similar ties to liberal institutions. A critical intellectual difference, however, is that Black liberals’ analyses and policy ideas originated in their experiences in the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, movements that emerged from the African American community. Black liberals’ analyses, limited though they are, continue to be shaped by their Black constituents, who help fund civil rights organizations and elect them to office. It is important to question the implications of the fact that Black conservatives’ arguments originate in white conservatives’ arguments, and that Black conservatives are in no way answerable to a Black constituency.

The historical distinction between white liberals and white conservatives is also a critical one. White liberal patrons and allies have historically allied themselves with, not against, Black interests. During the civil rights struggles, the only place white conservatives could be found was implicitly or explicitly beside Bull Connor, Strom Thurmond, Lester Maddox, and George Wallace. The white conservatives with whom Black conservatives are allied tried to obstruct the very civil rights legislation which even Black conservatives concede was necessary to create what they insist is now a largely discrimination-free America.

“The white conservatives with whom Black conservatives are allied tried to obstruct the very civil rights legislation which even Black conservatives concede was necessary to create what they insist is now a largely discrimination-free America.”

Today Black conservatives belong to a Republican Party thoroughly tainted by racism, whose leadership openly pursues a “southern strategy,” employing racially polarizing tactics. Ironically, even today white conservatives remain ambivalent over the desirability of attracting more Blacks to conservative causes and to the Republican Party. Those favoring outreach to Blacks and other minorities have various motives. Pragmatic Republican strategists want to capture at least some of the solid Black support for the Democratic Party. Further, many conservatives recognize that sometime in the 21st century a majority of the U.S. population will be people of color. Given the historical role played by the traditionally politically liberal African American community as a catalyst for change, many mainstream white conservatives believe conservatism must become more inclusive if it is to survive.

Additionally, many Jewish conservatives seek an alliance with Black conservatives, who represent a sector within the African American community that will unite with them in support of Israel. The result is to diminish African American support for Palestinian and Arab causes and the related criticism of military ties between Israel and South Africa.

The more extreme conservatism of Patrick Buchanan and the extreme right wing of the Republican Party is, however, explicitly racialist. As Margaret Quigley and Chip Berlet detailed in the December 1992 issue of The Public Eye, the Right has always seen the African American civil rights movement as part of a

A neutral term used to describe someone or something, such as in law, as non-religious in character.

Learn more

humanist plot to impose communism on the United States. This faction identifies sexual licentiousness and “primitive” African American music with subversion.

“As crucial as white conservative patronage has been to the careers and visibility of Black conservatives, it should not be viewed as their sole support. Mainstream, liberal, & even progressive institutions have promoted them to their present-day status & levels of influence.”

Patrick Buchanan wrote a well-known column titled “GOP Vote Search Should Bypass Ghetto” in which he argued that Blacks have been grossly ungrateful for efforts already made on their behalf by Republicans, who had already done more than enough to obtain their support.

It says much about his willingness to “sleep with the enemy” that, even after this notorious column and after Buchanan’s outspoken racism during his 1992 run for the Republican Party’s presidential nomination, Thomas Sowell could still write in a 1992 column: “If and when he [Buchanan} becomes a viable candidate on his own, perhaps in 1996, that will be time enough to start scrutinizing his views and policy proposals on a whole range of issues.”

As crucial as white conservative patronage has been to the careers and visibility of Black conservatives, it should not be viewed as their sole support. Mainstream, liberal, and even progressive institutions also have promoted them to their present-day status and levels of influence.

“It is similarly noteworthy that while Black conservatives received an exceptional amount of publicity throughout the 1980’s, the most intellectually sophisticated and nuanced group of African American scholars and theorists received next to none.”

Robert Woodson’s most notable award came from the moderately liberal MacArthur Foundation, which awarded him a $320,000 “genius” grant in 1990. Walter Williams is a featured commentator on National Public Radio’s “All Things Considered.” Both Williams and Sowell are syndicated columnists. Shelby Steele produced and hosted a public television documentary on Bensonhurst in 1990. Articles by or about Sowell, Loury, Steele, and Carter appear regularly in such established outlets as The New York Times, the Boston Globe, Dissent, Time, and Newsweek. Shelby Steele, Glenn Loury, and Tony Brown were among those featured in the January/February and the March/ April 1993 issues of Mother Jones magazine, in a two-part article on urban poverty.

It is similarly noteworthy that while Black conservatives received an exceptional amount of publicity throughout the 1980’s, the most intellectually sophisticated and nuanced group of African American scholars and theorists—progressives such as bell hooks, Angela Davis, June Jordan, Manning Marable, Adolph Reed, and Cornel West—received next to none.

Between January 1980 and August 1991 three prominent newspapers, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Philadelphia Inquirer, published eleven op-eds, fourteen articles, and thirty reviews by or about Thomas Sowell, Shelby Steele, and Walter Williams. However during this same period, three prominent progressive African American scholars, bell hooks, Manning Marable, and Cornel West, had no op-eds, no articles and no stories by or about them in these same three newspapers.

“As a nation, we have never committed ourselves to providing as basic human rights a quality education for each and every child, universal high-quality health care, and a decent place to live for all people.”

This is, in part, a reflection of the conservatism that pervaded the political culture of the United States throughout the 1980’s. But the question remains: How and why did a group of African Americans so unrepresentative of Black majority political opinion and so uninvolved in the affairs of the African American community come nonetheless to be anointed as race spokespeople, even by white institutions claiming to reflect liberal democratic ideals? From the perspective of the African American community, there is nothing democratic about the ascendancy of Blacks who demand that we acquiesce in fundamentally racist interpretations of who we are.

Conclusion

The principal complaint of most African Americans against Black conservatives, particularly the intellectuals featured here, is that they provide cover for policies that do grievous harm to Black people. But the potential harm inherent in Black conservatism is a danger to all Americans.

June Jordan has observed that problems which first appear in poor African American communities—substandard schools, AIDS, violent crime—always eventually appear in middle income white communities. At that point they leave the realm of the “culture of poverty” and become an “American problem.”

“So long as the devastating inequities that characterize American society persist, and racism continues to exacerbate these inequities, there is absolutely no way to make meaningful, much less provable, statements correlating peoples’ values with their socioeconomic status.”

The United States has never allowed full citizenship rights for all its citizens. It has never built a social culture devoid of racism, An ideology that assumes a hierarchy of human worth based on the social construction of gender difference. Learn more , anti-Jewish An attitude toward social identities that can be mobilized to justify discrimination, state/vigilante violence, and exploitation. Learn more , A form of heterosexism that devalues and scapegoats gay, lesbian, and bisexual people and people in same-gender relationships. Learn more , or classism. Our economic system has never provided full employment at a sustainable wage. As a nation, we have never committed ourselves to providing as basic human rights a quality education for each and every child, universal high-quality health care, and a decent place to live for all people.

So long as the devastating inequities that characterize American society persist, and racism continues to exacerbate these inequities, there is absolutely no way to make meaningful, much less provable, statements correlating peoples’ values with their socioeconomic status.

By tying poor African Americans’ poverty to race and our supposed slavery-flawed culture, Black conservatives insult African Americans. They also divert attention from June Jordan’s observation that Black problems inevitably become problems of the larger society. At some point, white Americans and middle income Americans in general are going to be forced to confront the fundamental problems caused by this country’s severe maldistribution of resources and its intolerance of diversity. Black conservatives delay that confrontation and in so doing, they do the entire country a grave disservice.

By uncritically promoting Black conservatives, liberal and progressive institutions nor only undermine their own stated principles, they exhibit a not-so-subtle form of racism. As Adolph Reed Jr. points out: Who would listen if the word “Italian” or “Jew” were substituted in Black conservatives’ characterizations of African Americans? We should be clear that stereotyping and victim-blaming is not more respectable because it is done by a member of the group being demeaned.