“A few years ago,” the Washington Times reported in a story last year, “Jeff O’Holleran said he began to realize that he was different from the other boys he knew…. Yesterday, he said, it was time to come out of the closet. In the middle of a crowded university dining area, he took to the podium and announced, ‘I’m Jeff, and I’m a conservative.’ Coming Out as Conservative Day had begun at the University of Colorado.”

To judge by the amount of media attention, the campus Right had a good year. Or a good two years. Besides Coming Out as Conservative Days, students staged a Capture an Illegal Immigrant Day, published increasing numbers of campus newspapers with decidedly right-wing editorial policies, and lobbied for a Student Academic Bill of Rights on multiple campuses and in several state legislatures to bring attention to what they saw as silenced conservative voices on campus (see flyer).

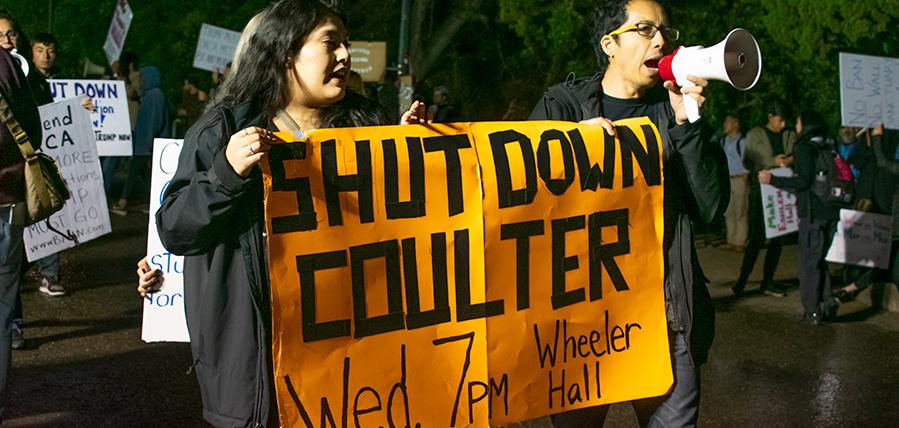

They conducted campaigns accusing professors of liberal indoctrination and discrimination. When they brought in big-name conservative speakers, the events were provocative enough to tempt some pie-throwers from the opposition. And in 2003 administrators at Southern Methodist University shut down campus Republicans’ affirmative action bake sale, a popular tactic where conservative students illustrate the ills of disparate treatment by discounting prices for white women and people of color, while burdening white men with paying full price.

That certainly was a lot of activity.

Conservative student activists have developed a reputation of being fiercely committed, well trained, and fearless. They have shed their “button-down” image once associated with the anti-Communist Young Americans for Freedom in the 1960s and emerged as an energetic, largely secular co-ed force with a message and a megaphone. The mainstream press regularly describes college conservatives as growing in visibility and sophistication.

But how influential have they been? Very, if the test is the depth of ties they’ve built with the broader conservative establishment and their grooming for future leadership. A dismal failure, if you consider the freeze on real campus debate and the few new campus recruits they’ve attracted to their cause. But that might change if they learn to reach the evangelical Christian students who have thus far remained lukewarm to the largely neoconservative campus activists.

Swimming Upstream

Student organizing is limited by a highly transient population with fewer ties to campus life and less free time than in the past. Given the academic and financial pressures on today’s college students, any political activity probably should be considered an achievement. Both progressive and conservative students complain of the difficulties of organizing on campus. But conservative students work with far fewer numbers than their progressive counterparts while making more noise.

Although the number of entering college students who identify as on the Right is slowly growing, conservative student activists were historically a distinct minority on campus, and remain so. In 2003, 24% of first-year students identified as conservative or very conservative, compared with 31% identifying as progressive (see graph).1

Progressives not only have a slightly larger pool to work with, they are also more successful at recruiting. According to PRA’s sampling of U.S. colleges in our study of campus activism, Deliberate Differences, progressive political groups outnumber conservative ones on campuses by a ratio of 4:1.2 There is, after all, a gap between holding an opinion and encouraging others to agree with you. In fact, when we conducted over 100 interviews on eight campuses, we found only a small core of conservative activists, usually no more than a handful, working at any one school.

While the number of conservative students who act upon their beliefs — the activists — remains very low on campus, this may be attractive in itself. Running the campus conservative paper or the lone conservative group on campus can offer some students a structure in which it’s acceptable to feel different. But a self-defined sense of being an outcast is too individualistic to create a particular culture that attracts large numbers of recruits. Their success lies not in numbers but in their deep relationship with supportive organizations on the Right.

A Targeted “Minority”

Conservative students manage to champion a range of issues, from opposing abortion and same-sex marriage, to supporting the Bush administration’s foreign policy positions on Israel or the war in Iraq. No other consistent, national campaign by conservative students is as pervasive, however, as the attack on their own schools.

The campus Right is well known for its ability to deliver a consistent message across campuses: Student conservatives are an abused minority because of their unpopular political ideas and the dominance of liberal thinking. Crafting such a message and sticking to it is a key lesson of adult organizations supportive of the campus Right.

Typical comments from conservative students reflect this sentiment. “I’ve made conservative statements in class and been hissed,” reported a Northwestern student. A student at Washington and Lee University explained, “I was sick of being ridiculed by my teachers for being a Republican.”

They demand that colleges change to make the campus safe for conservative students and faculty and to make room for a “diversity of thought.” The manner in which they deliver this message is pretty consistent across campuses, heavily depending on sarcasm, personal attack, and activities geared to attracting publicity. For instance, two college seniors wrote in an op-ed in the conservative paper MassNews, “To be openly conservative at Wellesley is to contend daily with emotionally driven ‘testaments,’ shrill libel and hateful words in the name of ‘progress’ or ‘peace.’…What makes us better citizens and leaders is diversity of thought — not melanin levels. If we had more professors who disagreed with the tyrannical majority, more of us would hear both sides.”3

All the conservative students we interviewed for our study earnestly described their experience in this way. Sometimes they added that they felt like outcasts, because progressive activists outnumber them at their schools. Rich Lowry, editor of the National Review, explains, “If you’re a conservative, usually you kind of like going against the crowd a little bit. That’s sort of the appeal of it.”4 The message works so well that it has actually become a frame for conservative students’ reality — “conservative student as beleaguered underdog.” The frame succeeds in two other ways. It identifies the speakers as the conservative voice on campus, and the publicity it draws is part of a long-ranger strategy on the larger Right to increase public criticism about the current state of higher education.

The Clash of Ideas

The higher education agenda of various conservatives in the larger Right is much more complex than angry student speech about liberal bias on campus. At its roots, it has to do with traditionalist conservatives’ claim that progressive reforms of the past few decades are a fundamental threat to higher education that changed who goes to college and what students learn once they get there.

Their glib claim that liberals have taken over higher education is connected to reality by a slender strand of truth. Affirmative action and curricular reform have taken hold because of progressive organizing on campuses. For instance, women’s studies programs launched in the 1970s and 80s to fill gaps in the college curricula have grown to a network of nearly 400 campus-based programs. Colleges’ support for multiculturalism similarly created the potential for profound changes in how students view and study people of color.

Power dynamics among social movements change all the time, so it was only a matter of time before a backlash developed, led by conservative strategists and ideologues who saw these achievements as threats to a key institution they felt they once controlled. Evidence of this backlash can be seen in adult conservatives’ decadelong attack on affirmative action and repeated attempts to cut federal funding for financial aid (see box).

Not all adult conservatives’ views find secure homes among student groups on campuses. But when neoconservative students win media attention for their claims that they are not safe to express their ideas on campus, or when they organize against a particular liberal idea like affirmative action, they make it easier for these other conservative criticisms of higher education to win attention.

Cutting federal support for financial aid, attacking multiculturalism and area studies in the academic and mainstream media, a call for the return to a traditional, Eurocentric curriculum, and a lament on the general decline of the meaning of a college degree — all are examples of a larger, off-campus neoconservative agenda to take back higher education.

One segment of the campus Right grows without much support from outside organizations. Conservative Libertarian thought has a small but loyal following on campus, fueled in part by a youthful resistance to social regulation and the attraction of Ayn Rand’s books, and reinforced by the support for free market capitalism in many university economics departments. Its strengths are a clearly defined social and economic ideology and a third party electoral infrastructure.

Once only visible at elite schools like the University of Chicago, libertarian student groups have begun to crop up at a variety of schools, including public universities like Appalachian State in North Carolina.

Grooming the Next Generation of Leaders

Tygh Bailes, on the other hand, is a poster child of how off-campus organizations can help students use campuses as a training ground for a career in conservative politics. While a student at Hampden-Sydney College, “Tygh used techniques he learned at The Leadership Institute’s Youth Leadership School to become Student Government President.”5

Many observers have admired the well-developed network of national organizations like the Leadership Institute that support the Right on campus.6 In providing organizational support, off-campus networks, and communications strategies to help conservative students create a campus presence, their goal is more leadership development than movement building. As one website clearly proclaims, “The Leadership Institute’s mission as to identify, recruit, train and place conservatives in politics, government, and the media.”7

While not monolithic, together these groups train and sustain a conservative student voice on campus, teaching students not only how to campaign for student government but also to amplify their message to attract the largest audience.

Along with the Leadership Institute, national organizations like the Young America’s Foundation, Intercollegiate Studies Institute, the Center for the Study of Popular Culture, and the Fund for American Studies offer generous resources to campus-based activists who readily receive them (see box). These groups are well funded by prominent foundations on the Right, including three of the largest: the Bradley, Sarah Scaife, and Olin foundations. According to Young People For, a branch of the liberal People for the American Way, these five organizations together spend over $30 million a year to support conservative college student programs.8 Meanwhile, there is no equivalent funding or infrastructure on the Left.

The dozen or so campus-supportive organizations mostly offer training off-campus. A critical mass of students travel to retreats, conferences and internships, where they discover and define a group identity by learning and living together. If the identity of many conservative students on campus is akin to an oppressed minority, the collective character of participants at these events is one of joy and relief at having found eager, ambitious, and focused fellow students ready for action. The opportunity to identify with a conservative student culture certainly exists, but students often have to travel off-campus to find it. One student testified:

I have faced so many obstacles, at times I have felt like abandoning my fight for a balanced campus….However,…after attending the National Student Conservative Conference last August,… [I understood] that I was not alone in my struggle, [Back at school] I strongly voiced my commitment towards conservatism. On one of the most liberal campuses in America, I received the highest number of votes in all of the races run and easily secured my [student government] seat.9

Some of the national organizations offer an impressive collection of incentives for joining the team. These include free or subsidized trips to conferences, academic credit coupled with opportunities for fellowships and internships, chances to study conservative economic and political theory with well-respected scholars, access to conservative decision-makers in Washington, and the opportunity to jumpstart a career on the Right.

It does not matter if they reach only few. The elite of the campus-supportive conservative organizations are identifying young conservatives and grooming them for leadership, while others, like Young America’s Foundation or Students for Academic Freedom, provide basic training for future foot soldiers in the larger conservative movement.

Organizations like the Fund for American Studies, which runs conservative summer courses at Georgetown University, or the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, which maintains a publication list of nearly 200 conservative titles directed at college students, are committed to bringing conservative political theory to students. The Fund for American Studies has offered summer school courses on conservative political and economic theory for 35 years, reflecting its commitment to the long-term strategic value in serious academic study of conservative ideology.

One might think the effect of the approach of organizations like the Fund for American Studies is diminished by their outsider status and the small number of students they reach. But their influence is augmented by other conservative institutions inside higher education, including endowed chairs, policy centers and graduate fellowships funded by the same set of conservative foundations.10

Some networks have been in place in for decades. For instance, the organizational founders of three conservative student-supporting groups are among the luminaries of the neoconservative movement. William Simon and Irving Kristol of The Institute for Educational Affairs (IEA) decided to fund conservative campus papers in 1979. Simon was Secretary of the Treasury under Nixon, and Kristol has been a publisher of several important conservative journals and is a fellow at the neoconservative think tank the American Enterprise Institute. IEA merged with the Madison Center, founded by William Bennett, Secretary of Education under Ronald Reagan, and Allan Bloom, the University of Chicago intellectual who decried the liberal drift of higher education.

Eventually the Collegiate Network—as this campus newspaper grants program came to be called—moved to the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, which had been founded 43 years before by William F. Buckley, Jr., the father of conservative campus activism and author of God and Man at Yale.

The organizations that came together in support of campus publications do not necessarily share the same perspective on all issues, including “strong government”-style neoconservatives like Kristol, with traditional “small state” conservatives like Buckley. They are, however, willing to share responsibility for supporting campus publications as a key element of conservative strategy.

When conservative students take advantage of the resources available from such campus-supportive organizations, they can accumulate the generic personal assets of leadership development and political skills building. Beyond that, however, choosing to associate with these organizations is a good career move — it enhances their resumes and allows access to the necessary networking that helps secure a job in an official political world dominated by conservatives. They can feel close to power, a heady attraction for careerists and non-careerists alike.

A list of conservative alumni of campus-supportive programs reads like a Who’s Who of current Right strategists and spokespeople. Karl Rove, the White House Chief of Staff, Sen. Rick Santorum, (R-PA), Grover Norquist, head of Americans for Tax Relief, and Ralph Reed, the former director of the Christian Coalition and current Georgia political candidate, have all been associated with the College Republicans or their National Committee. Edwin Feulner, President of the Heritage Foundation, and Richard Allen, Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, were involved with the Intercollegiate Studies Institute as students.

Ann Coulter and Dinesh D’Souza, prominent members of conservative campus speakers bureaus, each started a conservative campus publication with the assistance of the Collegiate Network. Along with other prominent conservative pundits, they provide a key role in the larger media by amplifying the voice of the contemporary campus Right beyond its relatively small size.

Tygh Bailes now runs the Grassroots Programs at Morton Blackwell’s Leadership Institute. As Tygh’s staff bio on the Institute’s website says, “At The Leadership Institute, Tygh has helped train thousands of conservative activists to become more effective. In addition to speaking for The Leadership Institute, Tygh is also a sought after speaker for groups such as GOPAC and The Center For Reclaiming America.”11

The Campaign for “Academic Freedom”

There is no denying that conservative activists are creative in message delivery, consistent in focus across the country, and skilled in taking advantage of the political moment. All these aspects of conservative student organizing are important strategies developed with the help of the conservative institutes.12

The major conservative messages are that access to conservative political thought is not available on campus; that the big ideas on the Right are squelched when brought into classrooms by conservative students; and that there are very few faculty that teach conservative ideologies. The combined force of students and some off-campus strategists call for the return of “academic freedom” to U.S. colleges. The outcome of their actions, however, is just the opposite of their stated goals.

Ironically, instead of fostering open dialogue and debate, the conservatives’ version of the campaign for academic freedom has actually diminished, and in some cases silenced, political discussion. A professor from Metropolitan State College of Denver reported resorting to taping her own lectures as a kind of protection against being attacked.13 Another faculty member, this time from Monmouth College in Illinois, took her children out of school for a few days after challenging a visiting conservative and being harassed for it.14 Students we interviewed with views across the political spectrum said they could not rely on faculty for political mentoring. Almost all the professors we spoke with, both conservative and progressive, including those who teach political thought, reported they avoid getting involved with student politics.15 In effect, this aggressive conservative campaign has silenced both faculty and students who fear being attacked by critics on and off campus.

Students from all political backgrounds reported that they experience very little debate on campus about political ideas. It’s not that students avoid expressing their opinions, but there is limited interaction and even less dialogue with those who disagree.16 Granted that discussion across difference of opinion is not comfortable for many people for a variety of reasons, but this apparent lack of engaged conversation among students may be a symptom of something else. One hint of what that might be is the aggressively combative stance of many conservative spokespeople on campus.

What’s Next?

For many conservative students and their adult supporters, the system skillfully prepares the next generation of conservative leaders, using the campus as a rehearsal space. The common frame of conservative student as underdog resonates with many, and appeals to an apolitical sense of fairness on the playing field. It falls short, however, of an adequate set of principles that will tip the scales of public opinion and win students major victories, at least on campus.

The most telling void in conservative campus power is the lack of a mass base of student support. Currently, there is just not enough of a critical mass of mobilized and organized conservative students to call itself a movement, and what exists is just not growing fast enough. The one exception is the College Republican National Committee (CRNC) which claims 100,000 members and is its own “soft money PAC.” Rather than wielding the influence of a powerful united student voice, however, the CRNC’s purpose is “to make known and promote the principles of the Republican Party…[and] to aid in the election of Republican candidates at all levels of government,” as their chapter manual spells out.17

Strategists appear to have only a few choices. They could continue to work with the relatively small numbers of current conservative activists, helping them refine and amplify their messages for attention far beyond what their actual organizational size might warrant. They could build on a certain level of success, and leverage power from off-campus, by expanding alliances with national organizations like the Republican Party. They could encourage and support more groups that spontaneously develop around specific issues. The danger of this is that some groups may not completely agree with their benefactors. Because Libertarianism has some popularity on campus, it has been identified as a potential break-away group by young neoconservative leaders.18

A final choice is to expand the base, drawing from the large pool of non-politically active conservatives or even centrists. This is where conservative Christian organizations come into play.

It is too early to tell how much political force the Christian Right will have on secular campuses. But Christian evangelical campus groups are currently the largest growing category of campus organizations. Yet not all evangelicals are conservative. And organizations like Campus Crusade for Christ and InterVarsity Christian Fellowship have declined to join in with the largely secular network of campus-supportive conservative groups.

But as Christian evangelical ministry groups gain popularity on campus, their members can become targets for political organizing by both the Left and the Right. Progressive groups have already made some inroads in educating religious students through service learning programs, sometimes conducted by college chaplains that attract mostly apolitical students attracted to service projects involving social action, personal reflection, and academic credit.

On the Right, the Colorado-based evangelical powerhouse Focus on the Family offers internships and educational programs to students through its college student ministry. By reaching out to Campus Crusade and InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, the organization could generate mass mobilization much as the Christian Coalition engineered the transformation of apolitical evangelicals into politicized Christian conservatives in the 1980s.

Opposing same-sex marriage through state constitutional amendments may be a new area for campus work if strategists can peel away enough of a base among an age cohort more tolerant on social issues than their elders. Student groups may compromise in this area in order to attract new socially conservative constituencies to conservative activism.

Conclusion

Even though it has maintained a campus presence for decades, the conservative student “movement” is still in its adolescent development. It is old enough to appreciate mentors, accept support and run many of its own campaigns, but not mature enough to understand its organizational deficiencies or recognize its potential power. As long as the larger Right maintains its power base in electoral politics, there will be little incentive for students to do much more than run affirmative action bake sales and groom themselves for future leadership with the help of adult allies.

While small numbers of conservative students play out a seemingly limited role on campus, we need to pay more attention to the larger contest. These students enhance a “low intensity” form of attack on higher education curriculum and culture from the Right. Whether we like it or not, U.S. campuses are politicized. These multileveled attacks have begun to erode the work of progressive educators and policymakers and threaten the very academic freedom the Right insists it defends. Progressive student activism cannot protect universities on its own.

The natural defenders of a university system are its leaders and its supporters. University presidents, established faculty, trustees, fundraisers, and the media that covers higher education issues are beginning to recognize their collective power as defenders of quality, accessible higher education. Groups as distinct as the American Association of University Professors, American Philosophical Association and the National Women’s Studies Association are examples of national groups already voicing their opposition to the Academic Bill of Rights. Piecemeal attempts at appeasing conservative challenges may interrupt, but will not ultimately stop, the conservative move to claim the campus as its own.

Endnotes

- Linda Sax et al., The American Freshman: National Norms for 2004 Summary (Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA, 2005) 1. Available at:http://www.gseis.ucla.edu/heri/findings.html.

- Pam Chamberlain, Deliberate Differences: Progressive and Conservative Campus Activism in the United States, (Somerville, Mass: Political Research Associates, 2004), 2.

- http://www.massnews.com/2003_Editions/3_March/03…, July 11, 2005.

- Christopher Hayes, “Birth of a Pundit,” In These Times, March 4, 2005, [p?]

- http://www.leadershipinstitute.org/08-CONTACTUS/staffdirectory-bios-bailes.htm, July 21, 2005.

- See for instance, John Colapinto, “Armies of the Right: The Young Hipublicans,” The New York Times Magazine, May 25, 2003, 30-59; Joshua Holland, “Why Conservatives are Winning the Campus Wars,” http://gadflyer.com/articles/print.php?ArticleID=187, June 24, 2005.

- http://www.leadershipinstitute.org/01ABOUTUS/aboutus.htm, June 28, 2005. The Leadership Institute claims to have trained 40,000 students

- Young People For Foundation, “Conservative Youth–Focused Organizations,” training materials, 2004 and the 990 IRS form for the Fund for American Studies accessed athttp://www.guidestar.org/pqShowGsReport.do?npoId=275986, June 24, 2005.

- http://www.yaf.org/conferences/college/conference.asp, June 28, 2005.

- People for the American Way, “Right Wing Watch—Buying a Movement,”http://www.pfaw.org/pfaw/general/default.aspx?oid=2057, June 22, 2005.

- http://www.leadershipinstitute.org/08-CONTACTUS/staffdirectory-bios-bailes.htm, July 21, 2005.

- As recently reported in The New Yorker, a few conservative Christian colleges like Claremont-McKenna or Patrick Henry encourage students to sharpen their debating skills. Patrick Henry’s President Michael Farris says students “need these verbal-communication skills to defend their ideas. There’s no training like arguing against the best minds and then beating them.” Hannah Rosin, “God and Country,” New Yorker, June 27, 2005, 47.

- For instance, see the case of Oneida Mercanto in Jennifer Jacobson, “A Liberal Professor Fights the Label,” Chronicle of Higher Education, Nov. 26, 2004; Nikhil Aziz, “Campus Insecurity: The Right’s Attack on Faculty, Programs and Departments at U.S. Universities,” The Public Eye, Spring 2004.

- Personal communication.

- Deliberate Differences, 22-24.

- Ibid., 28-32.

- http://crnc.org/resources/ChapterManual.pdf, 53, July 13, 2005.

- David Kirkpatrick, “Young Right Tries to Define Post-Buckley Future,” New York Times, July 17, 2004, A1, A17.

- http://www.nas.org/nas.html#PURPOSE, June 24, 2005.

- Jerry Martin and Anne Neal, “Defending Civilization: How Our Universities are Failing America and What Can Be Done About It,” (Washington, D.C., ACTA, February 2002 edition) 2.

- Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind, New York, 1987, 256,262.

- http://www.goacta.org/about_acta/mission.html, June 24, 2005.