Roger Ross Williams is a television and film writer, director, and producer whose most recent project, the documentary God Loves Uganda, focuses on the work of American evangelical Christian missionaries in Africa. Williams decided to focus on Uganda after a bill that would make homosexuality punishable by death was debated in the country’s Parliament in 2009. His research for the project began with Globalizing the Culture Wars (2009), a report published by Political Research Associates (PRA) and written by PRA’s religion and sexuality researcher, Rev. Dr. Kapya Kaoma.

Inspired by the report, Williams began exploring the role of conservative evangelicals in fomenting the antigay attitudes that led to Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill. The missionaries featured in the film are part of the A movement originally identified and named in the 1990s by evangelical theologian C. Peter Wagner. The NAR has since become the leading political and cultural vision of the Pentecostal and Charismatic wing of evangelical Christianity. Learn more (NAR), a growing Neocharismatic movement within evangelical Christianity. One of its most prominent leaders, Lou Engle, appears in the film and has been a visible and vocal critic of gay rights and marriage equality in the United States. An article in the Spring 2013 issue of The Public Eye—“The Christian Right, Reborn”—analyzes the rapid growth and rising importance of the NAR.

Williams won an Oscar in 2010 in the category of Best Documentary (Short Subject) for his film Music by Prudence, which tells the story of a young Zimbabwean musician who overcomes her physical disability—and the Individual beliefs that favor one group over others, or disfavor a particular group, and/or laws, policies and traditions that inscribe such beliefs in institutions. Learn more she is subjected to because of it—to become an inspiration to others. God Loves Uganda, which is now being screened at film festivals across the United States (and internationally), is scheduled for limited theatrical release this fall. An edited version of this interview appears in the Summer 2013 issue of The Public Eye.

How did you find this story?

When I was making my last film, Music by Prudence, not only did I notice a church on every corner in Zimbabwe, and everyone was praying, but it was an intense spirituality. I had heard about the A form of heterosexism that devalues and scapegoats gay, lesbian, and bisexual people and people in same-gender relationships. Learn more in Africa and was reading PRA’s reports about what is going on and the bill in Uganda, and I knew that I had to get involved. I grew up in the Baptist Church, singing in the choir. But I was never accepted by them because of my sexuality, so I was obviously drawn to An umbrella acronym standing for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning. Learn more rights because of that.

You mentioned that you read PRA’s report on Africa [Globalizing the Culture Wars]. What other background research had you done on the subject?

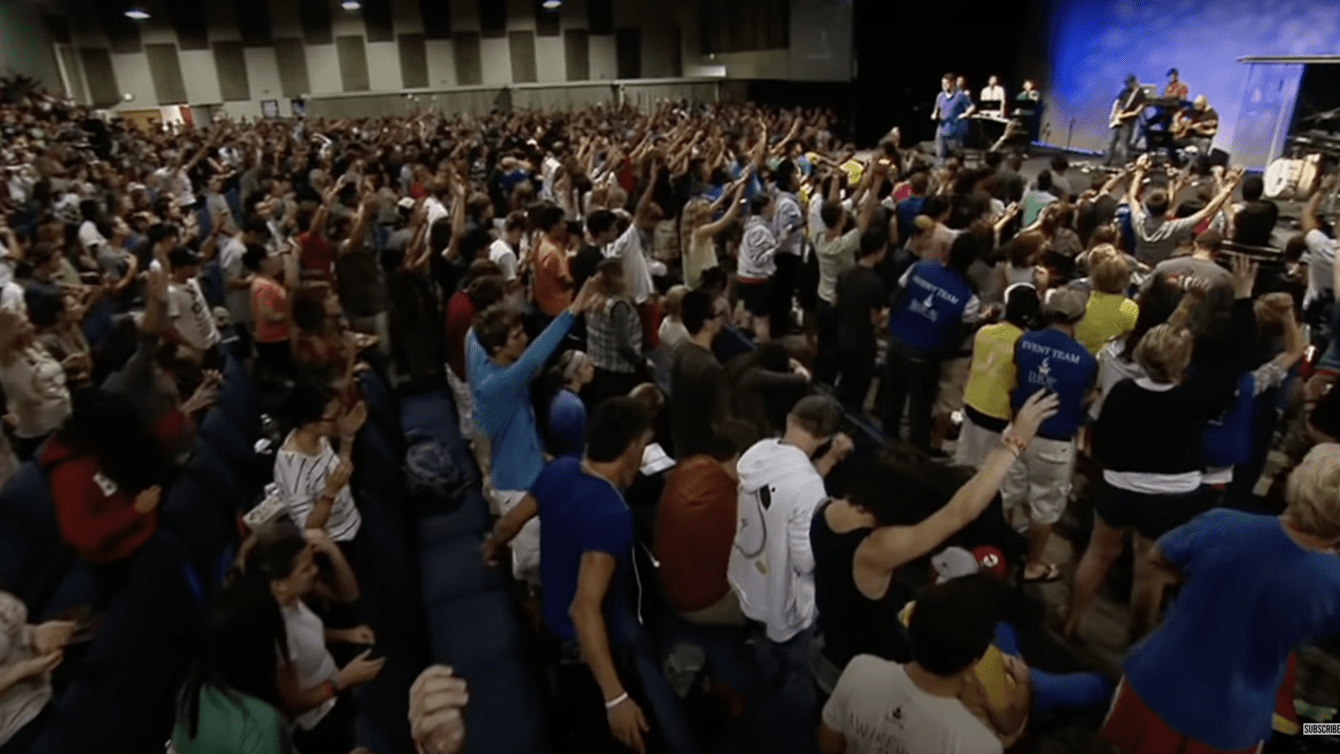

I really scrutinized PRA’s reports, and I also read the general media about the missionaries of hate. Then I started really looking into who the players were, and when I found out that [NAR missionary] JoAnna Watson had organized TheCall Uganda, an NAR event, I called her up and asked her if she wanted to meet for lunch. When JoAnna arrived, dressed in purple with an African head-wrap, I knew that I had a great character. I could already see in JoAnna what kind of American is drawn to a place like Uganda, and why. She was so passionate about Uganda and the work she was doing. She talked about the country like it was her project, “saving Uganda.”

How did you eventually connect with Kapya?

I was so focused on the American evangelicals that I didn’t even think about another voice in the film. For me, it was so interesting to go into a world where people hate me, where people want to see me in jail for who I am. Kapya’s reports gave me the historical background as well as the broad picture of what was going on. I did a long interview with Kapya, and later went to the Sundance Film Festival. The folks at Sundance thought that it was so much inside the world of evangelicals that it felt like an ad for IHOP [International House of Prayer, an NAR center based in Kansas City]. I wanted to bring in another voice. Then I looked at Kapya’s personal story and knew that that would be a good direction to go.

Most Americans couldn’t locate Uganda on a map. So what’s the case you make for why they should care about what’s going on there?

I think it depends on what audience you’re talking to. It’s important because there’s a possible genocide in the making, and American dollars being put into collection plates are feeding that potential genocide. If that happened, then people of faith in America would have blood on their hands. For the LGBTQ community in America, they should realize that the struggle for equality is a global struggle. This isn’t an isolated world anymore. It’s great that battles are being won in America, with state after state passing marriage equality, but we as Americans don’t want to wake up one day and realize that people in Uganda suffered or died. We have to view this as a global struggle, not just a struggle in our state or town.

Can you talk a bit about the nuts and bolts of making the film?

It takes about three years to make a documentary film—not always full-time, but pretty much. Documentaries are difficult because you have this story in your head, and that’s not always the story that ends up on the screen. But you try to get close to that. And you’re constantly raising money. So you shoot a little bit and then come back and raise money and you go back. So it’s a constant struggle and you have to be passionate. You have to be willing to pitch the film thousands of times to tons of people who listen to pitches all the time.

It would have been easier to make a film showing people who are advocating for LGBTQ equality. But you went straight at the opposition. I wonder if there are other reasons why you chose to focus on the other side?

What’s challenging for me as a filmmaker is for me to be in a place where I’m not comfortable. I wanted to look at the other side because I’m going on the journey, too. I wanted to understand the motivation, and where it comes from, and then the audience gets that experience. I’ve seen so many films that preach to the converted. So I was not interested in making another film about activism. [Human-rights activist] David Kato was the first person I met in Uganda. I took a bus from Rwanda and arrived in Uganda late at night. David Kato met me in my hotel the next morning, and he came with four activists. We sat down over breakfast, and he told me about what was going on in his country. He drew diagrams; he was amazing. I told him that I was interested in following the evangelicals, and he told me, “That’s the film you should make.” He told me that so many films had been made about him and his work. Ultimately, I decided that I wanted to focus on what challenged me, which is trying to understand the intolerance and where it comes from.

What did you learn about why Uganda in particular is so special to evangelical Christians?

There are biblical reasons, but there’s also the practicality of Uganda. The former president, Idi Amin, who was a Muslim, outlawed this kind of Charismatic Christianity, and the movement went underground. But when Idi Amin fell, it came above ground and became part of the pan-African movement. People embraced America for what it represented. It wasn’t colonialism; instead, Americans came in with money, and they helped rebuild schools, and people loved evangelicals for that reason. Uganda had the highest rate of HIV/AIDS, so the country was basically destroyed. America represents so much and helps Uganda so much. And a lot of that is faith-based. The aid money coming into Uganda is administered by faith organizations, which is part of the problem. Health care money for HIV/AIDS is not reaching the LGBTQ community, which is one of the issues we’re trying to tackle in our outreach.

There are many reasons why you oppose Lou Engle’s philosophy, but in God Loves Uganda, it feels like a sort of grudging admiration comes through. Is that fair?

That’s fair. Engle and his followers are amazingly well-organized. I love politics; this is like a political campaign. It’s run so well; it’s like watching the Obama campaign win an election. And that is fascinating to me. But from growing up in the church, I also understand spirituality and passion, and I respect that. I ended up respecting everybody in the film.

You realize that these people are actually quite charming and nice to hang out with. They’re passionate about their faith, and it’s intoxicating. At IHOP, I would be in the prayer room or at a service and would think, “I could get into this. I love passion and emotion.” People were praying for me, and praying that this was God’s work. I came to a revelation, after finishing the film, that maybe this is God’s work. I went into some of the prophet rooms at IHOP, and one prophet told me, “You are someone who has a huge influence over masses of people. You are a messenger.” I wondered how he knew all of this. But he’s right. I am delivering a message, and it’s one that they should listen to. They should put themselves in my shoes and consider what it’s like for a gay person to be in a culture when people are incited to violence.

I think that this is very hard for Christian fundamentalists to do, because they feel like they are the persecuted ones. No one is imposing a law to imprison and hang Christians in Uganda, and I wish that evangelicals and fundamentalists could look at the film objectively and have a discussion around it. And that’s happened in a lot of churches. When I went to Fuller Seminary [in Pasadena, CA], the largest evangelical seminary in the world, it was scary for me. But they were willing to have a discussion, because they were students. If anything is going to change, it has to come from the church, not the government. The church influences everything in Uganda.

How do you feel about your realization that you grew to respect these people, and even formed friendships with them, though they hate gay people?

For me, I realized that if there could be a dialogue, then things could be a lot different. Our worlds are so separate. I was a grand marshal at the gay-pride parade in San Francisco. I remember riding in the car along the parade route and seeing a man holding a sign that read, “I am an evangelical conservative with a gay son.” I pointed to him, and I remember that sign touching me. I thought, “Wow, there’s hope.”

As I hung out with these evangelicals in Uganda, we were having a great time. When we are together, we respect and understand each other. But when I was getting ready to leave, JoAnna [Watson, an NAR missionary] told me, “You’re going to be under a lot of pressure from the liberal elite, Roger, to make this film do what they want it to do. I want you to pray and not give in to these pressures. When you go back to New York City, and your life, you will be under a lot of pressure. Just remember the word of God.” My message to JoAnna since then (we’ve communicated) is that: “You’re going to be under a lot of pressure, JoAnna, to denounce the film. But just remember me.”

Early on, when I started filming with JoAnna, she told me that homosexuality is a sin. But she told me that she loved me. I told her that I love her, too. I asked her if she still wanted me to go to jail. She said, “No, I love you.” People like JoAnna think that they’re doing the right thing, and are so swept up with their passion for their particular version of the Bible and the End Times. I wanted JoAnna to go into the prisons and meet some of the gay people that she was preaching against. She claimed that she never read the Anti-Homosexuality Bill. That’s a cop-out.

Is it possible to generalize about the reactions of evangelicals to the film?

It’s mixed. Some of them come up to me and thank me, and some are completely closed off and will not accept responsibility. They may say, “The bill is really bad, but it’s not our fault.” Ugandans say that America creates these monsters and then walks away. They say, “Lou Engle is your problem, deal with him. Scott Lively [a prominent antigay activist who has delivered lectures in Uganda on the “threat” posed by LGBTQ people] is your problem, deal with him.” If a bunch of conservative evangelicals got together and said that they were going to condemn Scott Lively, people would have listened.

A common argument among conservative evangelicals is that the film represents a small part of evangelical Christianity, radical Charismatic evangelicals. How do you respond to that?

If that’s how you feel, speak out against that fringe element, not the filmmaker. This element has a huge influence in Uganda. They may be a fringe element in America, but in Uganda, they have the ear of the Parliament. My challenge to the evangelicals who claim they’re not represented in God Loves Uganda is this: Why are you not speaking out against it? Why aren’t you doing anything about it? I actually toned down a lot of the film. Anyone who thinks that this is edited to make evangelicals look crazy—I wish that they could see what was left on the cutting-room floor.

Do you do a lot of screenings for conservative evangelical Christian audiences?

I think we have requests from over 300 churches around the country. The conservative evangelical world is much harder to connect with, but we’ve made inroads. Going to places like Fuller, and having dinner with a fundamentalist professor, and being able to have a conversation about the film was great. Silence kills. Are you going to let people die or are you going to speak out against it?

What’s it like when you and Kapya appear together at the screenings?

The great thing about having Kapya there is that the critics are not as outspoken, because it is hard for them to get critical of another faith leader. Kapya tells the audience right off the bat, “I’m an evangelical … I want to be in this movie because as an evangelical I feel like I have to speak out against what is happening in Africa.”

Kapya must go to a lot of screenings?

Not as many as I want him to! The audience wants to see people in the film at screenings. Kapya always gets standing ovations.

You’ve said elsewhere that you’re drawn to stories of alienation in part because of your own background. Conservative evangelicals feel very much the same way—alienated from the mainstream culture. Do you think that led you to approach this film in a way that another filmmaker wouldn’t have?

That’s true. I’ve never really thought of it that way. But there is a certain feeling of being marginalized among evangelicals. It’s interesting, because in spending time at IHOP, I realized that it was a collection of people who all feel alienated, and who have come together passionately for something. So it was the oddball kids. The kids with pierced noses and tattoos. And I do think they feel demonized. So they don’t want to talk to the mainstream media; they feel that they’ve been persecuted.

It’s funny, because I identify with both sides for the same reason. I’ve always fallen into the middle of two worlds. Because I don’t feel totally connected to any one community or part of any one group, I can sort of see both sides. I think that’s what makes me a good filmmaker. The danger in that is it’s never enough for either side. So it’s not Christian enough for the evangelicals. They want it to be propaganda. And even on the LGBTQ side—they want a tool that they can use.

Is it true that you had a lot more material about two of the “superstar” preachers who appear prominently in the film, Martin Ssempa and Robert Kayanja, but left it out because you thought it would make the story too complicated?

The thing about hate—and I thought this would be a great theme for the film—is that when you unleash hate and intolerance, it devours everyone. So Martin Ssempa unleashed this tirade of hate into the world, and it came back at him. He accused Kayanja of being a homosexual, and then he got arrested for defamation of character, and it became a sordid, crazy trial. I became absorbed in that trial, and filmed pretty much the whole thing. And it was hard for me, as a filmmaker, to let go of that, because it was so fascinating, and there were so many twists and turns. But the audience could never follow that story—it involves pastors kidnapping each other’s assistants and all kinds of crazy stuff.

It’s crazy inside that world because the biggest business in Africa is religion. It’s the granddaddy of business. Every kid grows up wanting to be a pastor, because pastors are rich and they drive fancy cars and live in big houses, and they grow up watching pastors on TV. All the strongest television signals in Uganda are from Christian networks, Trinity and PTL. So the kids grow up watching the Emphasizes the power of a motivated spiritual life to gain wealth and influence. Often this is done through donating to a ministry that promotes the idea of the prosperity gospel. Learn more ; it’s so alive and well in Africa, and it appeals to Africans for so many reasons. They’re worried about their health and where their next meal is coming from, and all they have to do is follow Kayanja and give him their pence, and pray with him, and their problems will be solved—if not in this life, then in the afterlife. So there is competition, and the pastors compete with each other for their little slice of the pie. And it gets ugly.

Does the next project get easier, or does it all just start over?

It basically starts over, unfortunately. It gets a little easier, in that people will take your calls. That happens after you’ve won an Oscar. People will pay attention. There’s a lot coming at the people who make decisions. So you get past the gatekeepers to the people who make the decisions. But it still has to be a good project.

One of the things people would say to me, every time I would pitch God Loves Uganda, was, “We can see you’re passionate about this.” At one point, early in the process, I didn’t even have the personal stuff in my pitch. And it came out during one pitch as an afterthought: “You know: I did grow up in the church.” And he was like, “What? That’s your lead! You lead with that!” I hadn’t even processed how personal the project was. So that was the beginning. Now I’ve really processed it.

I imagine people want to do something from watching this. Do you have resources to connect them with?

We have spent a lot of time with a pretty extensive outreach and engagement campaign. The main focus right now is to get this screened in faith communities and get the word out. We have a number of discussion guides for different groups and people can download those on the God Loves Uganda website. It gives you background on why [this is happening in] Uganda, and leads you back to research from PRA’s reports. A lot of people write to me and ask, “Is my church funding hate?” We can’t investigate every church in America, but we can give you tools to help ask your pastor.

The documentary form is limiting in some ways: You’re seeing only what’s on screen, and not getting the background. But it can also be a powerful medium. What do you think its strengths are?

When you begin the editorial process, you have such a wealth of material and you’re taking nuggets of the best material and putting it together. A lot of the important stuff ends up on the cutting room floor. And you’re also telling a story. You have to tell a story so that the audience can have an experience; otherwise, people get too bogged down. In this film there’s a lot to process. What I tried to do is tell a very simple story. They [NAR missionaries] go to Africa, preach the Gospel, and there’s a fallout. The good thing about the documentary form is that it reaches a big audience. Everyone has access to it. If they want to go deeper, the sky’s the limit. So many people come up to me at screenings and tell me that they had no idea about what’s going on in Uganda. The documentary also has the power to transform people’s lives, which is what happens if you win an Academy Award. It’s unbelievable. If you have a good outreach campaign, you can actually create real change from a film.

If you had time and money for a sequel, have you thought about what story you’d like to tell next?

I would want to tell the big picture story of all of this, which is tough to crack. I think I would tell the political side of the story; the American congressmen and senators who are hyper-focused on the culture wars in Africa. It’s not the ground game. But I’d like to tell the stories of the deals being made between the leaders of the New Apostolic Reformation and politicians. Politicians are media savvy, and aren’t so easy to get to, so it’s probably something I can’t make. But it’s a sequel I’d like to make.

Also, I read in Christianity Today that Lou Engle is minor in the evangelical world; that he isn’t a player. If Lou Engle isn’t a player, why can you find him on YouTube with Michele Bachmann praying to end Obamacare? Why did he organize [Texas Gov.] Rick Perry’s “Response” rally? When I went to IHOP, I met Lou Engle’s former assistant who organizes all of the Tea Party rallies. All of these high-profile political figures seem to be “in bed” with Lou Engle. Lou is a problem for them, because Lou does not hold his tongue. He’s outspoken and a little rogue. He’s like Sarah Palin. He is a major figure, and when everyone else was running away from the fire in Uganda, he ran in and said, “I’m with you.” And he’s not afraid to sit down and do an interview with me, because he believes that he’s preaching the word of God.