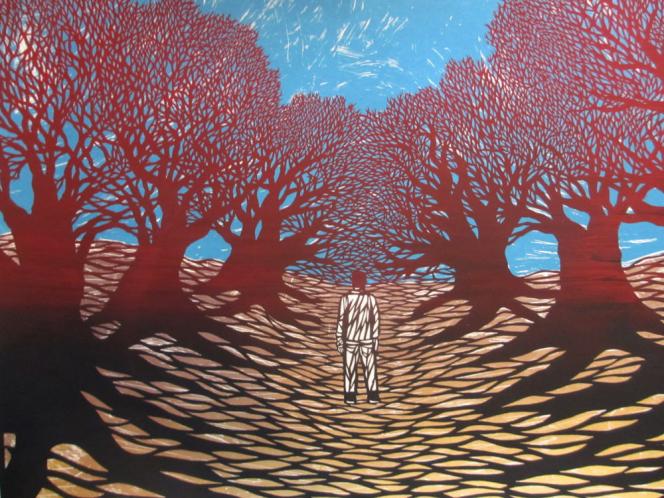

This spring’s Public Eye cover artist, Erik Ruin, is a Philadelphia-based printmaker, shadow puppeteer, and paper-cut artist whose work has been called “spell-binding” by The New York Times. He describes his art as oscillating “between the poles of apocalyptic anxieties and utopian yearnings, with an emphasis on empathy, transcendence, and obsessive detail.”

He stumbled upon printmaking and paper-cut art because they were the more affordable, available mediums being deployed by his punk rock peers. The democratic nature of the mediums he works in creates opportunities to challenge and reinvent the “rather hierarchical and elitist infrastructure that often surrounds/presents the art world.” For Ruin, printmaking in particular allows for a highly personal creative process that’s more accessible than a single painting.

Raised in Michigan, Ruin was a member of the UpsideDown Culture Collective in Detroit and other groups of radical-minded artists that eventually coalesced in 2007 to form the international Justseeds Artists Cooperative of printmakers (which began as a solo project of Josh MacPhee in 1998). His work is frequently made in collaboration with other artists and activist campaigns delving into social issues as well as more abstract underlying concepts. For example, “Prisoner’s Song,” his recent audio-visual piece with composer Gelsey Bell, was formulated to explore “what imprisonment and isolation reveals about the nature of humanity.”

Ruin says the connection between his art and activism isn’t always scripted though. Pointing out that activism often focuses on quantifiable goals and campaigns, Ruin is drawn to art-making partly because of its “resistance to utilitarianism,” noting that “the way an image or performance has the potential to impact people is highly subjective, variable and often mysterious even to its maker.”

While artists often use their skills to enrich and amplify the message of social movements, Ruin also observes that “art has the power to speak in different, sometimes stranger and subtler, ways—to say things that are only on the verge of being articulable otherwise.” Although his art often explores more abstract and subjective elements, the labor-intensive physicality of his process—he is currently creating a paper-cut piece more than 100 feet long—intersects with his convictions. “[L]abor and the struggle to be present with what I am depicting is of inherent value to me,” he says. “I feel like the effort to shape and bring forth the figures and landscapes in my work is an extension/reflection/origin of the empathy I hope viewers will experience when viewing it.”