In the last year, a record number of people took to the streets in protest of systemic racism and police violence. But over the same time period, women were sterilized without their consent at a detention center in Georgia; Amazon, with the help of anti-union consultants, sabotaged its workers’ attempts to unionize; and Black and Brown communities died in record numbers due to a mismanaged pandemic. These events bring into sharp question what equality really means in the U.S, and whether true freedom can be achieved within the existing systems in the U.S.

In his forthcoming book, A Wider Type of Freedom: How Struggles for Racial Justice Liberate Everyone (University of California Press, September 2021), Daniel Martinez HoSang looks at movements across the last three centuries—from fights against forced sterilizations, for domestic workers’ rights, and the environmental justice movement today—that illustrate the need to dismantle failed systems in order to rebuild an equitable society.

HoSang talked to PRA this June about the limitations of liberal ideas of freedom, and what a wider conception of liberation means.

PRA: The U.S. has always prided itself on its promotion of freedom and democracy. But you argue that the U.S version of both is limited. What does “a wider type of freedom” look like?

Daniel HoSang: Freedom is a contested concept, and it’s meant different things at different periods. Struggles against racial domination have yielded forms of freedom that aren’t just rooted in rights, access, inclusion, or even equity, but the transformation of systems. In that sense, freedom is a kind of process, a verb, that people are trying to work out and work through. But what links all of these cases together is the ways in which the participants, leaders, thinkers, and artists [within freedom struggles] understand that liberal conceptions of freedom are always limited—rooted in another person’s, nation’s, or community’s subordination. Freedom at someone else’s expense.

I’m drawn to movements where people rejected that, and thought about how the freedom that’s produced from any one person’s struggle can’t be limited to their own conditions.

Essentially, that true equality isn’t gained by oppressing one community over another.

Yes, and beyond that, to ask what are the terms under which we want to live? We could imagine equality under militarism, in which everyone has an equal opportunity to participate in militarism, or in market domination, or in bodily domination. Abolition [wasn’t about] “we want an equal right to own someone else.” It’s that no one should be owned. So it’s about transforming these institutions, not merely trying to be represented.

How did you choose the book’s four main themes: the body, democracy and governance, internationalism, and labor?

What’s at work across all [the movements I focused on] is they’re not just trying to figure out how to escape for themselves, or join the dominant formation, but about how the terms of that dominant formation change.

One example is the Black auto workers in Detroit in the mid- to late-1960s. They really saw, before many others, that this is a race against machines, and workers competing for the right to be exploited is going to end badly for everyone. That’s a much more common insight now in the days of Amazon, and DoorDash, and apps that control everyone’s movement. But then, it was a minoritarian perspective. Many others, certainly most White workers and their unions, said, “No, the good life is the right to work for General Motors.” But because of the histories of racialized labor exploitation, the Black auto workers saw this is not going to end well. They had a vision that technology could govern our lives in ways that we don’t have freedom over, so we have to change our relationship so that technology provides the basis for our liberation rather than for our further restraint. That’s a very pressing issue today, but it’s not surprising that workers of color, and Black workers in particular, had those insights first.

Your book shows how the U.S. was built on a colonial imagination, for oppressors to build and retain power. What are the vestiges of this in today’s society, and are they only vestiges or still our core logic?

I think it’s both. The fact that we have the largest military in the world [in terms of spending], with [military presence in at least 150] countries, and our nationalist orientation—that the U.S has an imperative to exercise domination and control over other nations—are all directly derived from colonial logics.

On the other hand, those logics have changed. Indigenous people within the U.S. have borne the brunt of colonialism as profoundly as anyone. Yet the incorporation of native peoples into the military, into contracting, is not a marginal issue. This is true everywhere the U.S exercises influence. People are incorporated into these systems. And this is important because it means that simply denouncing them and saying that they only represent forces of domination, exclusion, and limitation, and they don’t generate, is wrong. Because militarism is generative in partial ways for many subordinated people.

We run into this in terms of “defund the police” as well. People are capable of holding both things: seeing the violence policing causes, but also being socialized into the sense that that’s where your safety, protection, and jobs are derived from. You can’t just denounce it without thinking about what you’re trying to build as an alternative.

Do you think that we’ll ever see true equality without dismantling our current systems and rebuilding them from scratch?

No, certainly not. I think that’s the premise of the book. Seeking equality within systems rooted in domination is always going to be at someone’s expense. The only equality that’ll orient us towards is equal debasement or equal denigration.

You begin and end the book by looking at liberal responses to systemic racism in the U.S., from President John F. Kennedy’s idea of racial justice to the way people today are reading books on how to be anti-racist. What’s missing from those analyses?

What the liberal account doesn’t offer is: what is the basis—the actual material resources, structures, and relations—that we all need to live a free life? Which includes freedom from violence and coercion, but also freedom to be able to eat, to reproduce, to have kin, etc. The liberal account has nothing to say about any of that. I mean, they’re very clear, in fact, that none of that is guaranteed. So that’s partly what it is. That these abstract freedoms have never spoken to the material conditions of people’s lives.

And then the “how to be anti-racist” vision is always about psychological orientations, as if a shift in mindset would necessarily produce the new structures that support free and full lives. Again, that’s just not the case. You could shift your mindset and still be fully enmeshed in all of the prevailing structures.

There’s a big difference between being aware of microaggressions and seeing that everything needs to change in order to truly address systemic racism.

Yes, that’s absolutely right. And the [focus on] microaggressions is based on the assumption that in a liberal society, the baseline condition is people treating each other fairly. But that’s not the baseline. Because a competitive, militarized society produces aggression. So when we see aggression in one another or feel humiliated, that’s to be expected. And in fact, it would be profoundly surprising if that wasn’t the baseline of all of our interactions. We live in a formation that encourages people to get joy from other people’s humiliation and degradation. That’s long been part of our history. That’s another reason why these liberal ideals are so limited.

COVID-19 has revealed many kinds of internal injustices, including about who gets protected. But this isn’t the first pandemic we’ve seen. Why did COVID reveal these disparities in ways other pandemics might not have as clearly?

One thing that it reveals for those of us thinking about anti-racist work is that disposability is not just a phenomenon or a dynamic that falls along strict racial lines. Once you’ve created the notion that human life is not precious, that it’s disposable, far fewer people are safe than we might think.

Think about all the folks in long-term care facilities and nursing homes, many of whom are White, and even middle class. They were disposable as well because they were enmeshed in systems that focused on profit and limited their connections. Showing how much more vulnerable many of our social positions are pushes back against the very thin account of Whiteness that imagines it as a simple binary between vulnerability and protection. It’s never worked that way.

So many of these structures are failing the people that they purport to protect. If we think about the opioid epidemic and the companies that preyed on what were mostly White folks in the last 20 years, they were indifferent to their lives and suffering. I don’t know what kind of possibilities that emerges. People’s investment in these prevailing systems and the consent they offer to them is perhaps under more crisis and unraveling.

How do you see us using the momentum that we have in the current moment?

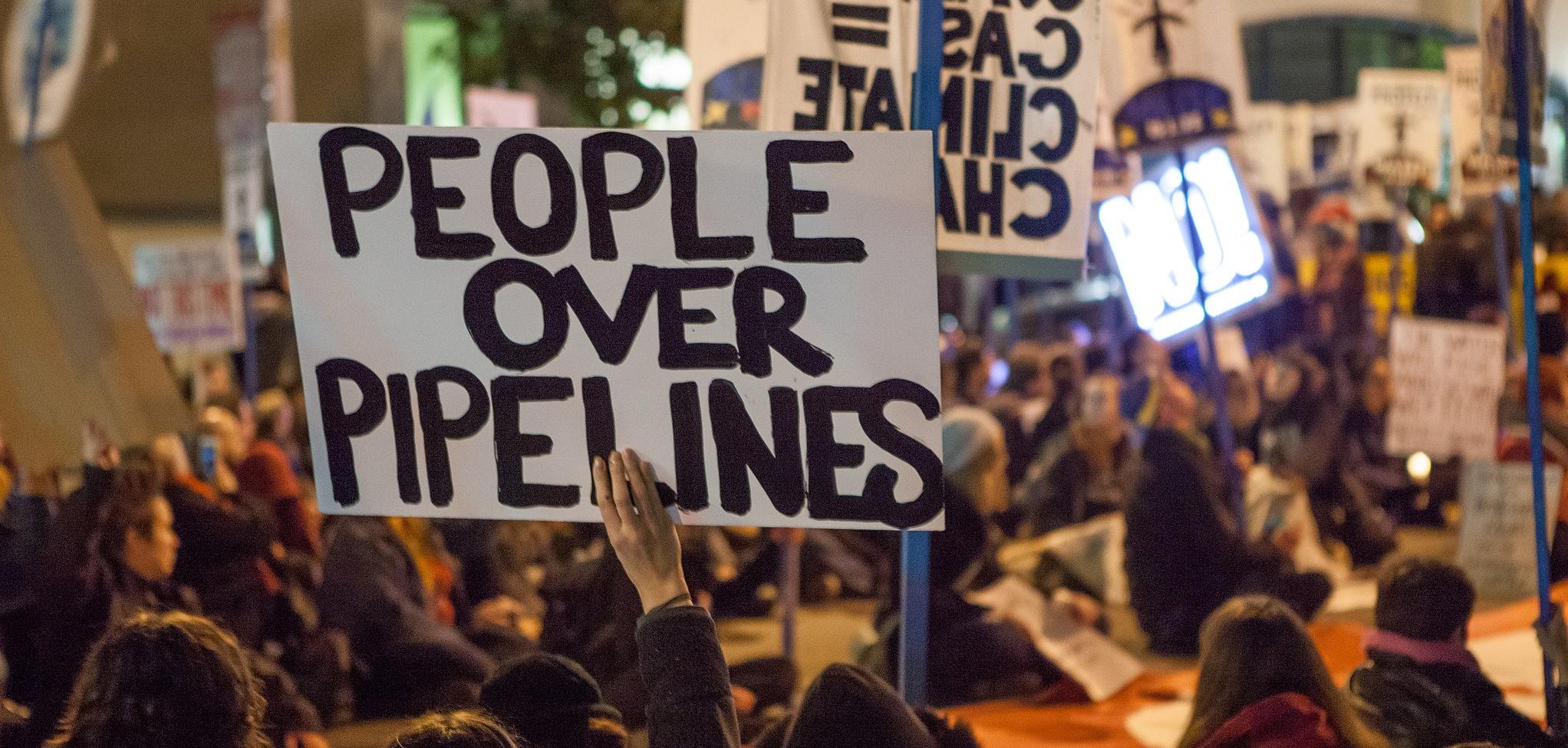

I don’t want to overly romanticize the mobilizations that happened last summer, because we saw how quickly they were countered and depleted. But what’s notable is the slow and steady work around abolition and mass incarceration. The very notion that “defund the police,” or alternatives to prison, are thinkable is itself the product of dozens of years of work. Or Standing Rock and Indigenous environmentalism. It’s long-term work.

Part of what [late Detroit-based activist and author] James Boggs said, is that, because so many of us are invested in prevailing systems, there’s no easy way out of them. And as we orient ourselves away from them, it’s going to mean lots and lots of struggles. And not just struggles between elites and masses, but between people.

You can see that in public education, where there’s been slow but steady work against the simplistic narratives spoon fed to students around U.S history and U.S exceptionalism, and wanting more critical thinking. It’s not just that there’s a backlash to it, it’s that so many people have been socialized into it that it seems unnerving to imagine a different form of education. I don’t even think of it as backlash as much as the necessary tumult that’s going to happen when people are compelled to rethink new possibilities.

Even with Amazon, the workers that voted against the union aren’t doing it because they think Amazon is so amazing, but because they’re afraid about the other option. I think that notion of “You have something here, are you ready to lose it?” will always haunt and undermine our efforts. That proposition—are you ready to lose something?—is not easy for anyone to answer. I think that’s what the possibility and the challenge is.