Coverage of the Far Right is often shortsighted, particularly in the U.S. When the Alt Right emerged into public view in 2015, there was a sense of shock as few understood how it had seemed to metastasize so quickly and without precedent. The Unite the Right rally in August 2017 shocked again, despite the fact that many of the groups that participated were decades old. Few reporters covering the melee were able to explain the continuity between past and present, to place the event in the long legacy of A social movement based on a belief in biologically determined racial hierarchies, often with the ultimate goal of establishing an all-White nation state. Learn more , and provide lessons about its vulnerabilities and threats.

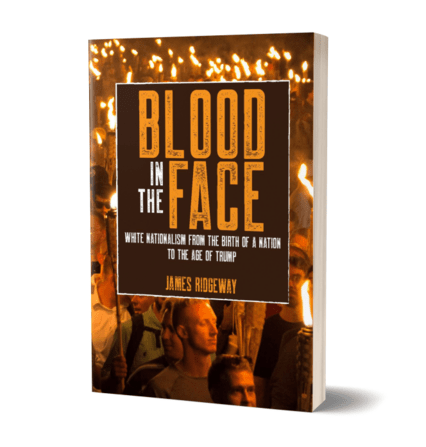

Investigative journalist James Ridgeway was one of the relatively few voices in both instances who clearly explained that these things had come before. That’s not surprising, given how foundational his work has become for understanding the U.S. Far Right. In 1990, Ridgeway released the now-classic book, Blood in the Face: The A U.S.-based White supremacist, Christian paramilitary group formed during the Reconstruction era. Learn more , Aryan Nations, Nazi Skinheads, and the Rise of a New White Culture. The book served as a chronological history of U.S. White ethnonationalism, back to its emergence in the 1800s, when fears of White dispossession fueled a more modern backlash to social progress.

The book inspired a documentary by the same name, which centered on a 1986 White supremacist conference that drew figures from the National Alliance, Aryan Nations, various Klan and neonazi skinhead crews, and speakers like Frazier Glenn Miller, who would go on to kill three people in a series of shootings at the Overland Park Jewish Community Center and Village Shalom retirement home in 2014. The vérité-style film includes interviews with racists speaking to their most shocking views, interspersed with news footage and videos that White nationalists were just starting to make as a form of propagandistic mass outreach. You can even hear a young Michael Moore in several clips, asking some of the armed conference-goers about their background and motivations in preparing for race war.

“As family farms were foreclosed upon en masse under Reagan’s new neoliberal consensus, working-class families were radicalized by inequity, but channeled their rage into a racist, rather than progressive, revolt”

Ridgeway’s book has been a go-to title for decades not just because of its accessible style, but because of its sheer breadth, tying together decades of history. This March, Haymarket Books is publishing a new edition of Blood in the Face, half of which is new material, and which Ridgeway began writing as Donald Trump was elected and the Alt Right became a household name.

Ridgeway’s history begins the 1700s with A term used to describe organizations, movements, ideas, and policies that oppose immigrants and immigration. Learn more ideas from the founders, but really shows the trajectory of organized racist movements starting in the mid-1800s, when the ethnonationalist Know-Nothing Movement helped launch a series of populist campaigns against “alien” German immigrants and Catholics, which served as an early archetype for later efforts to redirect the class anger of the White working class. Ridgeway takes us through the intervening years until, more than a century later, the 1980s “farm crisis” recapitulated the pattern established by the Know-Nothings. As family farms were foreclosed upon en masse under Reagan’s new neoliberal consensus, working-class families were radicalized by inequity, but channeled their rage into a racist, rather than progressive, revolt, as Generically used to describe factions of right-wing politics that are outside of and often critical of traditional conservatism. Learn more forces, including White nationalist militia groups like the Posse Comitatus, reinterpreted the economic attack through a conspiratorial and antisemitic frame. Bringing attention to these historical echoes, Ridgeway shows how The belief in the primacy of “the nation” as the most important political allegiance, that every nation should have its own state, and that it is the primary responsibility of the state and its leaders to preserve the nation. Learn more throughout U.S. history has repeatedly redirected legitimate popular anger away from those responsible and onto other marginalized people, driving “dual loyalty” conspiracy theories about Catholics, then Jews, and eventually about non-White immigrants generally.

“Ridgeway was 80 years old when Trump was elected, and, as he writes in the introduction, he would rather have come to the twilight of his life in a politically hopeful period, rather than watching the Far Right he studied for decades rise to a new level of power.”

Ridgeway’s history takes us through the first generation of the Ku Klux Klan—which claimed to have amassed 550,000 members across the South and helped shut down the radical transformations of the Reformation Era—to the publication of key White nationalist texts, such as the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and The Turner Diaries. He centers the role that A form of oppression targeting Jews and those perceived to be Jewish, including bigoted speech, violent acts, and discriminatory policy. Learn more played in building the White nationalist movement, as millions of Jewish immigrants entered the U.S. During the Klan’s second wave in the 1920s. Ridgeway writes, “the centuries-old antisemitic myth that Jews are at the heart of a worldwide conspiracy aimed at undermining civil society” followed them, re-rooting the legacy of European antisemitism in the emerging U.S. Far Right.

Ridgeway also traces the emergence of explicitly fascist groups like the German-American Bund during the lead up to World War II, and how the post-war fascist movement coalesced around both racist and antisemitic dog whistles and efforts to redeem Hitler’s cause by figures like George Lincoln Rockwell and the American Nazi Party, Willis Carto and the Liberty Lobby, and William Pierce and the National Alliance. Several decades later, this heritage, along with America’s history of Christian colonialism, helped establish the A White supremacist and antisemitic form of Christianity that believes White Europeans are descendants of the Lost Tribes of Israel. Learn more movement, which posits that people of color are not fully human, that Jews are descendants of the Devil, and which helped inspire dozens of grisly mass murders and terror plots that have connections to many White nationalist and militia organizations in the U.S.

The new edition of Blood in the Face expands this earlier history, as comprehensive as it was, and brings it up to the present. It includes extensive chapters about Trump’s legacy and White House, the influence of Steve Bannon on the global Far Right, the growth of national A style of politics that involves an effort to mobilize “the people” into a social or political movement around some form of anti-elitism. Such movements can be egalitarian or authoritarian, inclusive or exclusionary, forward-looking or fixated on a romanticized image of the past. Learn more and the Alt Right, and everything that pieces them together. Much as the original edition did, Ridgeway’s new book will stand alongside such journalistic classics on the Far Right as Leonard Zeskind’s Blood and Politics, Elinor Langer’s A Hundred Little Hitlers, or Daniel Levitas’ The Terrorist Next Door.

Ridgeway was 80 years old when Trump was elected, and, as he writes in the introduction, he would rather have come to the twilight of his life in a politically hopeful period, rather than watching the Far Right he studied for decades rise to a new level of power. There must have been a sense of urgency to this version of the book—and that Ridgeway had to write it. As it happened, he passed away shortly after finishing this new edition, in early 2021. That leaves the re-released version of Blood in the Face as the final piece in his profound legacy: a memorial in the form of what may be the best book written on the U.S. Far Right, from an author with the integrity to say that we all need to stand up and fight.