In the last thirty years, the rights of people who are marginalized by their sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) have improved rapidly in many countries.

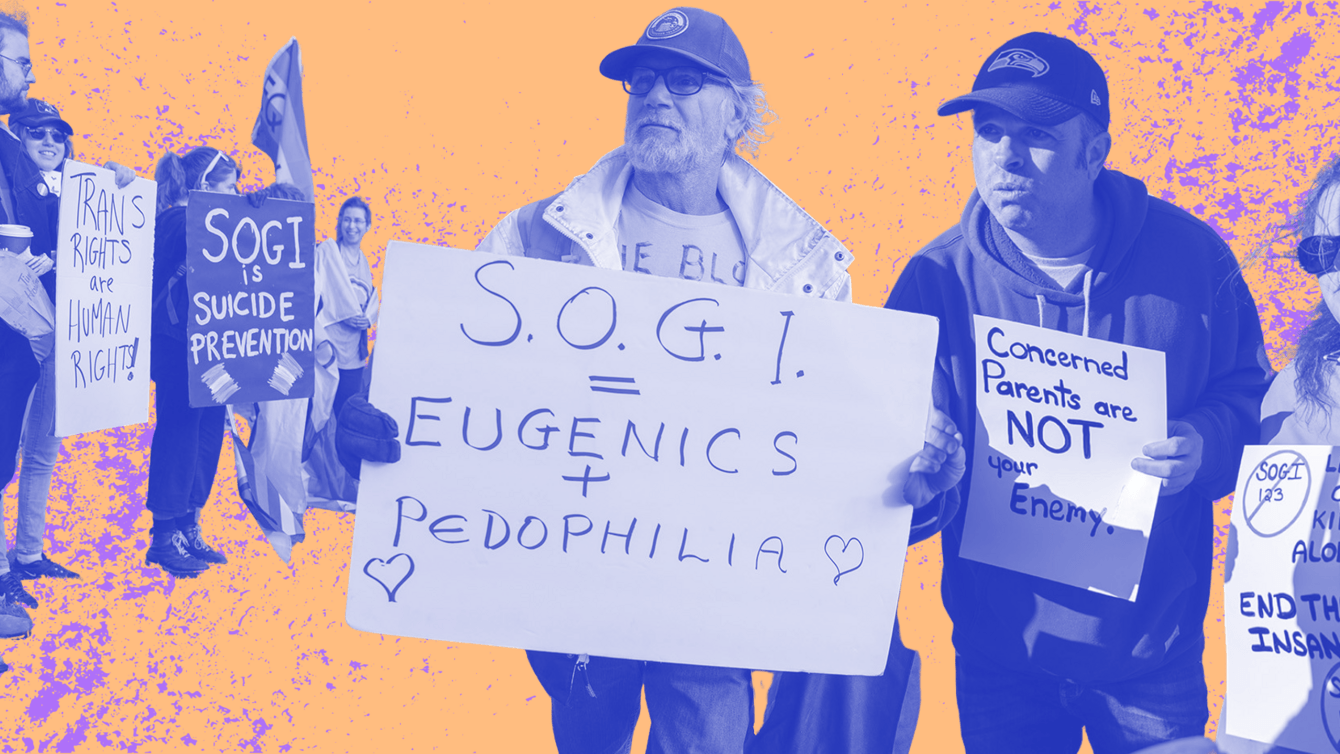

Yet such successes have not gone unchallenged. Global accomplishments in the field of SOGI rights… have been counterbalanced by a growing and, in recent years, increasingly globally connected resistance to such rights. In 2021, Hungary’s parliament passed a ban on so-called gay propaganda following the Russian blueprint of the previous decade, and in Ghana, 21 people were arrested for attending a training on SOGI rights organized for paralegals, echoing similar arrests in Egypt following a Mashrou’ Leila rock concert some years earlier. While resistance to SOGI rights is well documented[1], its global and networked dimensions are not yet fully understood. Especially in the last decade, this resistance rests predominantly in the hands of transnationally connected social movements—frequently with a conservative religious orientation—and conservative governments, actors that now also attempt to co-opt international human rights law.[2] These resistances employ many of the same transnational tools that have achieved widespread acceptance for LGBTIQ people. In other words, both those who seek the advancement of SOGI rights and those who oppose it use related strategies and instruments for mutually exclusive ends.

We define the varied and loose conglomeration of actors that compose the resistance to SOGI rights as politicized moral conservatives. The term applies when (a) the actors in question construct their political program around moral concerns, and (b) their positions on these issues belong to the conservative normative denkfigur, or figure of thought. Such conservatism privileges The belief in the primacy of “the nation” as the most important political allegiance, that every nation should have its own state, and that it is the primary responsibility of the state and its leaders to preserve the nation. Learn more over globalism, particularism over universalism, legal sovereignty over international law, A system of social control characterized by rigid enforcement of binary sex and gender roles. Learn more over equality, hierarchy over democracy, the collective over the individual, religion over the A neutral term used to describe someone or something, such as in law, as non-religious in character. Learn more , and duties over liberties. Thus, these moral conservative actors are not conservative in the dictionary sense of the term, as people inclined to reject new ideas. They are, instead, open to new ideas and strategies, including incorporating a language of human rights, if it furthers the development of the moral conservative program. Conservative is also the term these actors most commonly use themselves to describe their own work and agenda.

“Gender has not always been at the center of the mobilization of moral conservative actors, whose goals are almost always much larger than opposing women’s and SOGI rights.”

The global resistances to SOGI rights bring together actors that, at first glance, have little in common: Russia, a series of Muslim states, as well as other states from Central and Eastern Europe and the Global South; Evangelical and Orthodox Christians, Catholics, and Protestants; pro-life civil society groups and anti-migration right-wing populist parties, neoconservative media commentators, small businesses and homeowners, and entrepreneurs in the world of big business and economic consultancy.

Gender has not always been at the center of the mobilization of moral conservative actors, whose goals are almost always much larger than opposing women’s and SOGI rights, even if they have a forceful effect on these dimensions. Scholars have described gender as a symbolic glue that holds various groups of political actors on the political right together today.[3] However, politicized moral conservatism has a long and important history that predates the gendered focus.

The resistance to SOGI rights is the most recent spearhead of a broad and long-standing front of politicized moral conservatism, which has allowed moral conservative actors to reach new audiences and communicate their conservative ideas in novel, successful ways. Perceiving the contours of this larger picture requires tracing the long road to today’s resistances to SOGI rights, from the early origins of moral conservatism in the United States and in Europe in the 1970s to the hitherto largely national confrontations between conservatives and progressives globalized during the 1990s. Three factors help explain the transnational diffusion of moral conservative ideas during this time: the Vatican’s role at the United Nations, the rise of transnational A movement that emerged in the 1970s encompassing a wide swath of conservative Catholicism and Protestant evangelicalism. Learn more advocacy using a language of human rights, and the end of the Cold War and a subsequent religious turn in formerly communist countries.

“What American and European conservatives share is a nostalgia for a ‘market town’ or ‘main street’ capitalism—a romanticized capitalism of the past where everyone has an ordered place, typically implying fixed gender roles.”

The transnational actors that emerged out of these dynamics include groups like the World Congress of Families, which connects thousands of actors across borders and at annual summits…[and] diffuses Christian Right ideas far and wide, for example from the United States to Russia.[4] It is a central node in an increasingly coordinated, moral conservative transnational actor network that concentrates on resisting SOGI rights and plays the central role of convener, providing a networking platform for moral conservative actors and organizations. It is thus a group node inside the larger moral conservative transnational actor network. It lays claim to the concept of the ‘natural family’, by which World Congress of Families founder Allan Carlson means a cisgendered, heterosexual, married couple and their biological offspring.[5] Carlson has based his agenda on a narrow reading of Article 16(3) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which defines the family as the “group unit” of society entitled to protection by the state. In 1999, with significant involvement by Americans, the World Congress of Families organized a conference in Geneva. The meeting drew the attention of scholars because it was a moral conservative networking event in the backyard of the world’s most expansive intergovernmental organizations. However, that congress was only one in a long string of events the World Congress of Families organized. Through their regular conventions and declarations, the activists remap the discursive space of international human rights law, locate their claims in relation to specific articles in human rights documents and treaties, and develop a relatively consistent strategy and terminology through which to present their claims against SOGI rights. They use human rights language and copy many of the strategies of transnational collaboration from progressive NGOs.

The moral conservative actors in the network are today held together by their resistance to the SOGI rights movement. It would be more accurate, however, to say that they are held together by their resistance to their own construction of the SOGI rights movement. Moral conservatives construct their adversary by willfully misrepresenting the SOGI rights movement and transforming it into a symbol of everything else they reject: communism, global capitalism, liberalism, and international institutions. As moral conservatives link these disparate topics into one coherent narrative—coherent from their perspective—they come to identify as victims of the SOGI movement, but also as the privileged few who have special knowledge about the mechanisms that drive this movement and its role in global politics. The moral conservative narrative thus functions in a similar way to conspiracy theories, creating among its adherents an intense sense of identification with a shared cause.

In much of the literature on the Christian Right, moral conservatism is linked to The economic, social, and political position that centers individual freedom, undergirded by a weak government and unfettered, free-market capitalism. Learn more . Melinda Cooper, for example, connects the birth of the neoconservative ethos—with its insistence on traditional gender roles and the unpaid care work attributed to women—to neoliberal cuts to state spending.[6] Moral conservatives and their causes are also often funded by ultraneoliberal actors and groups. Our own findings confirm this picture yet also complicate it. The view that Western Europe and the EU are “quasi-socialist” states is relatively mainstream among American conservatives, but a sizable contingent of the moral conservative universe we studied, especially those coming from Europe, are actually in favor of the welfare state—as long as it clearly benefits “traditional families” and not single parents or other forms of households. What American and European conservatives share is a nostalgia for a “market town” or “main street” capitalism—a romanticized capitalism of the past where everyone has an ordered place, typically implying fixed gender roles.

“The transnational moral conservative network’s strategic goal is to diffuse and perpetuate its own structure and agenda of a conservative counterrevolution of sorts.”

In the complete moral conservative narrative that equates communism, global capitalism, liberalism, and international organizations, SOGI rights activists are assigned the role of the new revolutionaries. Moral conservatives depict SOGI activists as communist revolutionaries. They do so not just metaphorically, but quite literally, as in this quote from a Russian member of the World Congress of Families, where the red communist flag is likened to the rainbow flag: “The 1960s, ’70s [were] the continuation of this revolutionary trend that we experienced in Russia in a more straight forward violent, brutal, red form. And now it has this rainbow flag.”[7] Thus, moral conservatives see international organizations that support SOGI rights as communist institutions. When moral conservative politicians in Central and Eastern Europe criticize Brussels for being like the Moscow of the Soviet Union, what they mean is that they see the European Union as a communist project. This is a wild stretch of the imagination for most, but amid the crowd at World Congress of Families gatherings, it becomes hard to separate this all-encompassing narrative from reality.

The transnational moral conservative network’s strategic goal is to diffuse and perpetuate its own structure and agenda of a conservative counterrevolution of sorts. This may sound tautological at first. Yet it is important to recognize that the moral conservative narrative presented here is not only new and baffling for researchers interested in the phenomenon; it is also new for many of the activists who are drawn into transnational moral conservative networks. Most activists who attend World Congress of Families events listen to speeches by Allan Carlson and other regular attendees or pick up some translations from the book fairs and encounter this narrative for the first time.

The fact that the World Congress of Families perpetuates this narrative each time and in all locales where a summit takes place is significant. In the last [three] decades, moral conservatives have built up this narrative to identify and construct SOGI rights—and the institutions that support them—as the main focal point of twenty-first century ideological struggles. In conjuring a vision of a SOGI revolution, moral conservatives can become the counterrevolutionaries. All other strategic goals follow from this overarching narrative. The self-proclaimed counterrevolutionaries do have the strategic goal of blocking SOGI rights.

According to the moral conservative agenda, a win on the abortion front, the homeschooling front, or on The idea that people’s religious views should be neither an advantage or a disadvantage under the law. Learn more is de facto a step toward blocking SOGI rights. For moral conservatives, all these claims hang together. It is important to recognize that in the global resistances against SOGI rights, the above arguments flow into each other smoothly. For the moral conservative audience, it makes up one global, coherent narrative.

- Endnotes

- Tina Fetner, How the Often used interchangeably with Christian Right, but also can describe broader conservative religious coalitions that are not limited to Christians. Can include right-wing Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Mormons, and members of the Unification Church of Sun Myung Moon. Learn more Shaped Lesbian and Gay Activism (Minnesota: Minnesota University Press, 2008); Conor O’Dwyer, Coming out of Communism: The Emergence of Lgbt Activism in Eastern Europe (New York: New York University Press, 2018).

- Clifford Bob, Rights as Weapons: Instruments of Conflict, Tools of Power (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019); Cynthia Burack, Because We Are Human: Contesting Us Support for Gender and Sexuality Human Rights Abroad (Albancy, NY: SUNY Press, 2018).

- Eszter Kováts and Maari Põim, eds., Gender as Symbolic Glue. The Position and Role of Conservative and Far Right Parties in the Anti-Gender Mobilizations in Europe (Brussels: FEPS in cooperation with the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2015).

- Kristina Stoeckl and Dmitry Uzlaner, Moralist International. Russia in the Global Culture Wars (New York: Fordham University Press, 2022).

- Allan C. Carlson and Paul T. Mero, “The A concept of family, used by the Christian Right, defined by traditional gender roles frequently used to advance an anti-LGBTQ, anti-feminist, “family values” agenda. Learn more : A Manifesto,” The Howard Center for Family, Religion & Society and the Sutherland Institute 19 (March 2005 2005), accessed 2016-08-24 15:05:39.

- Melinda Cooper, Family Values. Between Neoliberalism and the New Social Conservatism (New York: Zone Books, 2017).

- Interview with a Russian member of the World Congress of Families, 2017.