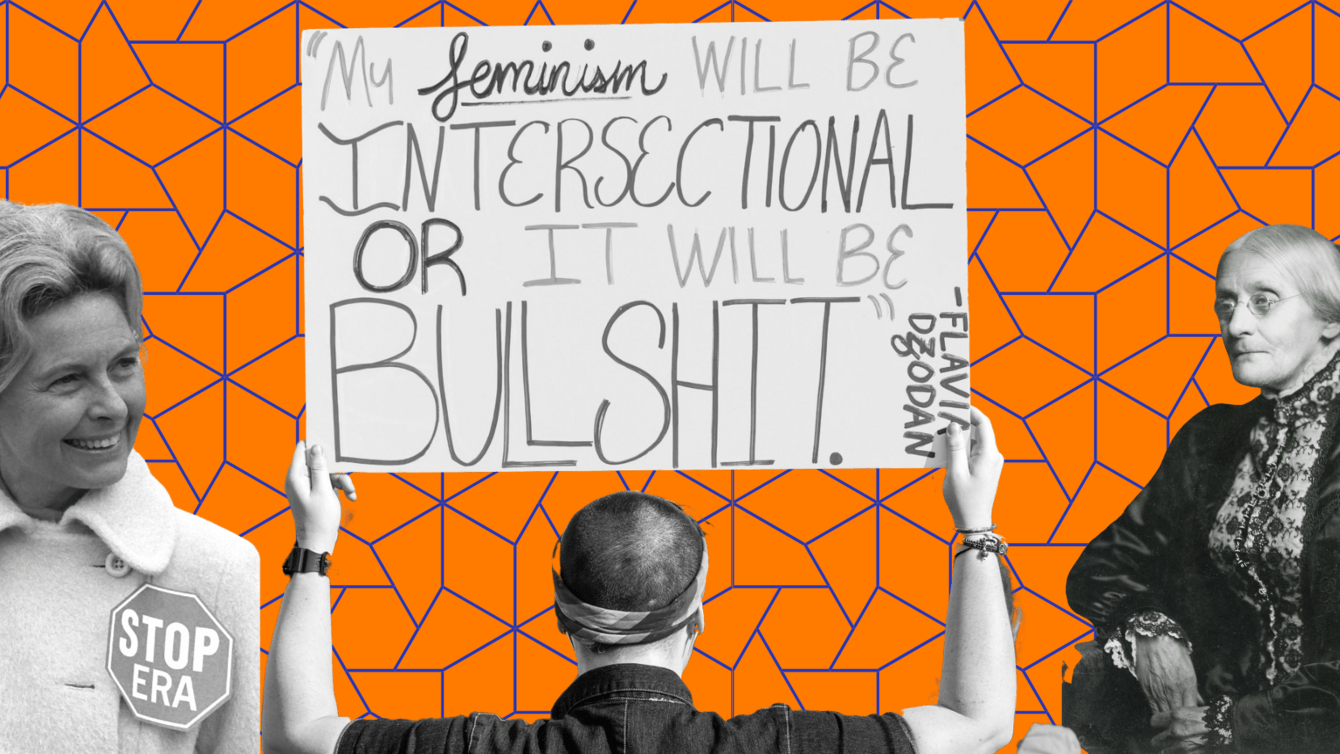

Sometimes a feminist is a feminist even though she dedicates her time to the dispossession and ostracism of a group of women. Female anti-feminism and right-wing feminism are distinct phenomena, yet contrary to some views on the matter, both exist in the West. The first category is relatively well-established: to evidence it, one can point to available data which shows that 46 percent of women voters in the 2024 election voted for U.S. president Donald Trump, up from 39 percent in 2016,[1] even after a jury found him liable for sexual abuse.[2] On the other hand, when it comes to pinpointing a feminism on the Right, there is no consensus. Systems of Both a system of beliefs that holds that White people are intrinsically superior and a system of institutional arrangements that favors White people as a group. Learn more and imperial capitalism shaped the birth of European feminisms, often molding them ideologically. Yet today, whenever anti-trans, nativist, and A movement that emerged in the aftermath of Roe v. Wade, a decision which prevented states from outlawing abortion under most circumstances. Learn more figures of the Euro-American moderate and Far Right self-designate as feminists, they are routinely received by others as insincere, invalid, or prima facie impossible.[3] (The right-wing Heritage Foundation-funded group “Women’s Liberation Front” is a case in point.) “You can’t have a right-wing feminist,” says Britain’s leading lesbian “socialist” columnist, emblematizing this view even as she spearheads the assault on trans lives.[4]

In my book Enemy Feminisms: TERFs, Policewomen and Girlbosses Against Liberation, I conversely offer a 200-year overview of cissexist, colonialist, nativist, White-nationalist, whorephobic, capitalist, eugenicist, carceral, and even pro-forced birth forms of Western women’s rights activism. I take seriously these enemy feminisms, even as I insist that Left antifascists must oppose them, because reckoning with these self-described feminisms is necessary for understanding how to defeat them.[5] While feminist commitment is a sine qua non of any rigorous or principled antifascism, some articulations of women’s rights can be and have been fascisms.

This possibility becomes especially apparent in the context of mass disillusionment with liberal feminism and amid various discursive exoduses from the scene of postfeminism, such as “tradwifery,” “the femosphere,” and “4B.”[6] Well-justified reflexes towards radicality, rejecting received forms of feminist mobilization, sometimes collapse into nihilist, individualist, edgily trad, or misandrist-separatist femopessimisms.[7] The feminism of cisness, however, has spread like a pogrom. Today, it is unsurprising to find self-described feminists at the forefront of policymaking to deny gender-affirming healthcare or make bathrooms and sports lockers cissexual at all costs, in the name of women’s rights.

”I take seriously these enemy feminisms, even as I insist that Left antifascists must oppose them, because reckoning with these self-described feminisms is necessary for understanding how to defeat them.”

There is an awful sense of familiarity about this latest right-wing counterrevolution in feminism. When it comes to mob-like zeal spurring sisters-in-arms toward a purge of “the Unwoman”—a chameleonic figure of fantasy who threatens to usurp, invade, or dishonor womanhood—we have been here before, multiple times.[8] Fifty years ago, a minority of cissexists—notably the group Gutter Dykes—mounted physical and ideological attacks on trans lesbian organizers in the women’s liberation movement, whom they charged with “invading and draining our lesbian community.”[9] Far from inherent to the movement, anti-trans feminism first arose as the counterinsurgent retort to sex-radical utopianism: a pessimistic response to a gender- and family-abolitionist efflorescence that was generally welcoming to trans women and aimed to communize care beyond the private household while generalizing “transexuality [sic],” as Shulamith Firestone put it, toward letting a thousand genders bloom.[10] Building on Alice Echols’s historical account of the U.S. women’s liberation movement’s fragmentation, I locate anti-trans feminism’s origins in the swamping of revolutionary feminism by a reactionary female biological and cultural The belief in the primacy of “the nation” as the most important political allegiance, that every nation should have its own state, and that it is the primary responsibility of the state and its leaders to preserve the nation. Learn more circa 1973—one that still calls itself radical to this day.[11]

But continuities can be found even further back. Over a hundred years ago, the modern feminist project of “women’s policing” took off in Britain as an anticommunist, antisemitic, anti-vice crusade against a fictional sex-trafficking panic about “White slavery” that was itself a backlash against feminist advances.[12] One of the innovators of this “cop feminism,” the lesbian radical and ex-suffragette militant Mary Allen, was a passionate devotee of Mussolini and later Hitler. While many disillusioned suffragists turned to socialism and communism in the interwar period, one radical feminist UK thinktank designated the soon-to-be Blackshirt leader Sir Oswald Mosley parliament’s top member.[13] Several British ex-suffragettes came to believe that “Fascism alone will complete the work begun…by the militant women from 1906 to 1914.”[14]

Meanwhile, in the U.S., the A U.S.-based White supremacist, Christian paramilitary group formed during the Reconstruction era. Learn more ’s women leaders and spokeswomen aligned themselves with the feminist movement’s radical fringe by supporting the Equal Rights Amendment when it was first introduced in 1923, just as they had supported the Nineteenth—as a weapon against Black voters. Fifty years later, post-Jim Crow and the Voting Rights Act’s passage, segregationist White women mobilized with Phyllis Schlafly to oppose feminism and the ERA. But back in the twenties, “KKK feminism” advocated for female access to divorce and child custody, and berated “the selfish man who insists that woman’s only place is in the home.”[15] Clearly, these race-hierarchized visions of sexed emancipation—for “respectable” non-sexworking White cis women only—were fascistic. But if they were not really feminism, then neither was the thought of Mary Wollstonecraft or Susan Anthony.

“Far from inherent to the movement, anti-trans feminism first arose as the counterinsurgent retort to sex-radical utopianism.”

Much contemporary thought treats such buzz-cut, white-hooded, and black-bloused examples as non-feminisms, implying that these fascist actors’ contradictory commitments must mean that their avowed feminism is necessarily false, trolling, or simply mistaken in referring to itself as such. In this view, “fascist feminism” is an oxymoron; fascist femininities and discourses “instrumentalize” or “wield” the language of feminism in order to dupe.[16] In contrast, the imperialist and White supremacist aspects of canonical liberal legacies like Wollstonecraft’s or Anthony’s can be admitted to and apologized for without calling into question their status within feminism or, for that matter, feminism’s integrity.[17] The literary world can apparently talk all day about the sins of the suffrage foremothers, never doubting for a moment that the feminism in question can be separated from the, say, An ideology that assumes a hierarchy of human worth based on the social construction of racial difference. Racism as an ideology claims superiority of the socially constructed category, White, over other racialized categories based on the false idea that race is a fixed and immutable reality. Learn more , without losing its core shape. Feminism, for us, after all, is a word that inherently means liberatory politics.

I understand that it can be profoundly upsetting to sit with the proposition that some feminisms have been deadly to indigenous lifeways, dangerous to sex workers, and even, weird as it may sound, misogynistic and patriarchal.[18] It can be tough to get one’s head around Western feminism’s role in the counterrevolutionary logic of cisness, a modern notion that has harmed all women by bifurcating and hierarchizing us in relation to maternal potential, very narrowly defined. The temptation is strong to immediately say, “OK, but what about anti-feminists’ much, much bigger role?” Yet none of this justifies institutionalized avoidance of oppressive feminisms. If they are such a minor thread in human history, what’s wrong with getting to the bottom of them?

The past decade saw a welcome attempt to reckon with “White feminism.” Although the questions “ain’t I a woman?” and “what chou mean ‘we,’ white girl?” have roiled organized Western womanhood since at least 1851, the putative Whiteness of some feminisms has received a greater level of scrutiny.[19] Picking up pace in 2013 before seemingly peaking in 2021—and spurred by books from Europe, Australia and North America by Ruby Hamad, Mikki Kendall, Jessie Daniels, Rafia Zakaria, and Kyla Schuller among others—this development catalyzed a much needed, heartening, and generative reflection.[20] From the hashtag #solidarityisforwhitewomen to the critique of some feminists’ reception of the “Karen” meme as a “slur,” the global North finally witnessed prolonged debate on the subject of “nice White ladies.”[21] This afforded many of us new insights into the racializing effects—and exclusions, witting or not—of contemporary and historic activism, while offering intersectional tools and heuristics designed to broaden the movement.

Inevitably, some of the media reception of these race-critical ideas betrayed a desire to sidestep a deeper reckoning with the anti-liberatory freight of certain kinds of pro-woman politics: the Observer thought the bigger injury was making “well-meaning but imperfect people feel terrible about themselves” while the NYT focused on the theory that internal criticisms of the Women’s March were being fueled by Russia.[22] (Elsewhere, the term “White feminism” is scorned outright as a “tool to dismiss second wave feminists.”[23]) Confronting complicities is hard; it is easier to condemn regrettable feminist moments and then issue a blanket premature recuperation: mistakes were made and that was bad, but feminism is still good, which means that feminists are never the “real” enemy. By avoiding a deeper reckoning, White cis feminism has reflexively denied the possibility of feminist harms.

“Confronting complicities is hard; it is easier to condemn regrettable feminist moments and then issue a blanket premature recuperation: mistakes were made and that was bad, but feminism is still good, which means that feminists are never the ‘real’ enemy.”

If there is hope today for the renewal of an internationalist feminism against cisness[24], it might be found in Western feminism being exposed to—and perhaps breaking open in confronting its limits in the face of—Zionist feminism. The latter’s global campaign used since-debunked Israeli government claims of sexual violence perpetrated by Hamas to justify the acceleration of genocide in Palestine post-October 7, 2023.[25] Although Anglo-American media will no doubt continue burnishing the IDF’s image via machine gun-wielding Israeli “Zionesses”—“lionesses of the desert” who so vividly embody the seduction of gendered settler-colonial power qua rape revenge in the anti-“White slavery” mode[26]—their credibility is hurt, perhaps irretrievably so.[27]

Concomitantly, anti-Zionist feminist organizing is growing, even in the heartlands of Empire. It is nourished on Turtle Island by groups like the Palestinian Feminist Collective, a group whose antipatriarchy organizing begins with—but does not stop at—opposing the occupying state.[28] Feminist activists all over the world have been radicalized, if not directly by Palestinian feminists’ analysis of gendered settler-colonialism, then by the unholy spectacle of the reproductive genocide itself.[29] This includes trans activists who have been at the forefront of Gaza solidarity protests, not least because, as the U.S.-based A term used for someone whose gender is not (exclusively) the one they were assigned at birth. Learn more Law Center argues, “trans liberation is inherently anti-colonial and inseparable from the struggle for Palestinian freedom.”[30]

An optimistic reading of available signs points to the possibility that grassroots anti-colonial feminism is on the ascendant. And the signs are many: The multinational “Feminist Call to Strike for Gaza” on International Women’s Day[31]; Ni Una Menos, South America’s anti-femicide movement; the Kurdish “invading socialist society” known as Jineolojî, under the banner of jin jiyan azadî (woman, life, freedom), in autonomous north and east Syria; and the small “Transfeminist International” platform from Greece, to name a few. The collective song of revolutionary feminism can be heard in DIY estrogen undergrounds, abortion networks, transformative justice teams, prison-abolitionist accountability collectives, and in family-abolitionist and disability-liberationist communes attempting to communize care while dreaming of dismantling—for all—the tyrannies of wage, state, and market.[32]

We didn’t choose the relationship of enmity, but it is only through fighting it out that we will make it obsolete.

- Endnotes

- Pew Research Center, “An examination of the 2016 electorate, based on validated voters,” PRC, August 9, 2018, http://pewresearch.org/politics/2018/08/09/an-examination-of-the-2016-e…; Linley Sanders, “How 5 key demographic groups voted in 2024,” AP News, November 7, 2024, http://apnews.com/article/election-harris-trump-women-latinos-black-vot….

- Barbara Rodriguez, “Jury finds Donald Trump assaulted, defamed E. Jean Carroll,” The 19th, May 19, 2023, https://19thnews.org/2023/05/e-jean-carroll-donald-trump-verdict/.

- Typical headlines about the unlikelihood or impossibility of anti-trans, anti-abortion, right-wing feminisms include: “Conservatives find unlikely ally in fighting transgender rights: Radical feminists,” Washington Post, February 7, 2020; “There’s No Such Thing As a Pro-Life Feminist,” New York Magazine, November 30, 2021; “Trans-exclusive feminism is not feminism,” Daily Free Press, April 27, 2023.

- Julie Bindel, quoted in Sarah Ditum, “Feminism’s blue future,” Tox Report (Substack), October 15, 2024, http://sarahditum.substack.com/p/tox-report-70-feminisms-blue-future/.

- Sophie Lewis, Enemy Feminisms: TERFs, Policewomen, and Girlbosses Against Liberation (Chicago: Haymarket, 2025).

- On the tradwife phenomenon, see: Mariel Cooksey, “Why Are Gen Z Girls Attracted to the Tradwife Lifestyle?” The Public Eye, Spring/Summer 2021, http://politicalresearch.org/2021/07/29/why-are-gen-z-girls-attracted-t…. On the term “femosphere,” see: Jilly Boyce Kay, “The reactionary turn in popular feminism,” Feminist Media Studies, 1-18, 2024. On the uptake of the Korean “4B” trend, see: Rebecca Davis, “Sex Strike,” Slate, November 18, 2024, https://slate.com/life/2024/11/4b-movement-what-is-usa-meaning-2024-ele….

- I propose femopessimism as a term that can encompass both Asa Seresin’s landmark diagnosis “heterofatalism” and a range of resurgent non-heterosexual erotophobias. See: Asa Seresin, “On Heteropessimism,” The New Inquiry, October 9, 2019, http://thenewinquiry.com/on-heteropessimism/; Sophie Lewis, “Battlefield Ecstasies,” The Point, #32, May 23, 2024, http://thepointmag.com/politics/battlefield-ecstasies/.

- I take this term from: Patricia Elliot and Lawrence Lyons, “Transphobia as Symptom: Fear of the ‘Unwoman,’” Transgender Studies Quarterly 4 (3-4), 2017.

- The quoted phrase, putatively from the Gutter Dykes’ anti-trans leaflet at the 1973 West Coast Lesbian Conference, comes from: Barbara McLean, “Diary of a Mad Organizer,” Lesbian Tide 2 (10–11), May–June 1973, p. 36; see also: Sophie Lewis, “TERF Island,” Lux, issue 10/11, 2024, http://lux-magazine.com/article/terf-island/.

- “A day may soon come when a healthy transexuality would be the norm.” Shulamith Firestone, The Dialectic of Sex (New York: William Morrow, 1970), 58.

- Alice Echols, Daring to be Bad: Radical Feminism in America 1967-1975 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989).

- Raymond Douglas, Feminist Freikorps: The British Voluntary Women Police, 1914-1940 (London: Bloomsbury, 1999). On Mary Sophia Allen and the fascist origins of “cop feminism” in Britain, see Sophie Lewis, “Lipstick on the Pigs: Kamala Harris and the Lineage of the Female Cop,” The Drift, October 30, 2024, https://thedriftmag.com/lipstick-on-the-pigs/.

- Martin Pugh, Hurrah for the Blackshirts! Fascists and A form of far-right populist ultra-nationalism that celebrates the nation or the race as transcending all other loyalties. Learn more in Britain Between the Wars (London: Jonathan Cape, 2005), 112.

- Norah Elam (a.k.a. Norah Dacre Fox), “Fascism, Women, and Democracy,” Fascist Quarterly 1(3), 1935. Quoted in: Martin Durham, Women and Fascism (London: Routledge, 1998), 33.

- Mrs. Robbie Gill, “The Equality of Woman: Her Struggles of Yesterday, Her Triumphs of Today, Her Hopes for Tomorrow, by the Imperial Commander,” Women of the Ku Klux Klan, Inc., Little Rock, Arkansas, 1924, p.12; Linda Gordon, The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition (New York: Liveright, 2017), on “KKK feminism.”

- On historiographical uneasiness about feminist fascism, see: Sophie Lewis and Asa Seresin, “Fascist Feminism: A Dialogue,” TSQ 9(3): 2022, 463–479.

- Examples: Claire Hynes, “Wollstonecraft and Woolf deserve statues. But do they represent women like me?” The Guardian, December 8, 2020, https://theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/dec/08/wollstonecraft-woolf-…; Brent Staples, “How the Suffrage Movement Betrayed Black Women,” The New York Times, July 28, 2018, https://nytimes.com/2018/07/28/opinion/sunday/suffrage-movement-racism-….

- On feminist harm to Indigenous people, see: Kyla Schuller, “For Me, but Not for Thee,” Slate, October 25, 2021. On feminist harm to sex workers, see: Political Research Associates, “Anti-Sex Work Feminism and the Lived Reality of Criminalization and State Violence: A Roundtable Discussion,” November 23, 2021, https://politicalresearch.org/2021/11/23/anti-sex-work-feminism-and-liv…. On “misogynist feminism,” see: Susan Gubar, “Feminist An aggravated form of sexism that is a primary motivation for the Right, both as recruitment for and justification of its agenda. Learn more ,” Feminist Studies, 20(3): 453-73, 1994; see also: Enemy Feminisms, chapter 8.

- “Ain’t I A Woman?” refers to the famous speech by Sojourner Truth in 1851 at Akron, Ohio, which was subsequently transcribed in drastically different ways by other suffragists. For Marius Robinson’s version, see: “Women’s Rights Convention: Sojourner Truth,” Anti-Slavery Bugle, June 21, 1851, p.4 (reproduced by the National Park Service at http://nps.gov/articles/sojourner-truth.htm/). “What Chou Mean We, White Girl?” refers to the poem by that name: Lorraine Bethel, “What Chou Mean We, White Girl? Or, The Cullud Lesbian Feminist Declaration of Independence,” Conditions, 5: 86-92, 1979.

- Ruby Hamad, White Tears/Brown Scars (Berkeley: Catapult, 2019); Mikki Kendall, Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women that a Movement Forgot (New York: Random House, 2021); Jessie Daniels, Nice White Ladies: The Truth about White Supremacy, Our Role in It, and How We Can Help Dismantle It (New York: Seal, 2021); Rafia Zakaria, Against White Feminism: Notes on Disruption (New York: W. W. Norton, 2021); Kyla Schuller, The Trouble with White Women: A Counterhistory of Feminism (New York: Bold Type, 2021); Koa Beck, White Feminism: From the Suffragettes to Influencers and Who They Leave Behind (New York: Atria, 2021); Terese Jonsson, Innocent Subjects: Feminism and Whiteness (London: Pluto, 2020); Alison Phipps, Me, Not You: The Trouble with Mainstream Feminism (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020).

- On “nice white ladies,” see: Taylor Hathorn, “Jessie Daniels’ ‘Nice White Ladies’ Sparks Discussion about Race, Privilege in Jackson,” Mississippi Free Press, December 21, 2021; Ruby Hamad, “Strategic White Womanhood: Challenging White Feminist Perceptions of ‘Karen’” in Leigh-Anne Francis and Janet Gray (eds.) Feminist Talk Whiteness (London and New York: Routledge, 2025).

- Sonia Sodha, “‘White feminists’ are under attack from other women,” The Observer, September 26, 2021, https://theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/sep/26/white-feminists-are-u…; Ellen Barry, “How Russian Trolls Helped Keep the Women’s March Out of Lock Step,” The New York Times, September 18, 2022, https://nytimes.com/2022/09/18/us/womens-march-russia-trump.html/.

- Raquel Rosario Sánchez, “If ‘white feminism’ is a thing, gender identity ideology epitomizes it,” Feminist Current, July 26, 2017, https://feministcurrent.com/2017/07/26/white-feminism-thing-gender-iden….

- I take the phrase “feminism against cisness” from Emma Heaney’s anthology: Emma Heaney (ed.), Feminism Against Cisness (Durham: Duke University Press, 2024).

- Nicole Froio, “As Israel continues to use debunked claims of sexual violence to justify genocide, feminist movements must push back,” Prism, October 9, 2024, https://prismreports.org/2024/10/09/feminist-movements-push-back-agains…; Sophie Lewis, “Some of my best enemies are feminists: On Zionist Feminism,” Salvage, March 8, 2024, https://salvage.zone/some-of-my-best-enemies-are-feminists-on-zionist-f…. Operation Al-Aqsa Flood was, it has been claimed, a “trampling of feminism’s very foundations.” Amotz Asa-El, “The anti-Zionist sex,” Jerusalem Post, December 1, 2023, https://www.jpost.com/middle-east/article-775995.

- Nick Pisa, “Lionesses of the Desert: Inside Israel’s all-female tank unit taking on Hamas terrorists,” The Daily Mail, December 1, 2023, https://dailymail.co.uk/news/exclusive/article-12815095/Lionesses-Deser…. The term “Zioness” is an invention of “Zioness Movement, Inc.” a self-described “progressive” Zionist lobby group founded by the lawyer Amanda Berman. For more, see Alex Doherty and Sophie Lewis, “When Genocide is Feminist: Talking Zionist Feminism with Sophie Lewis,” ReproUtopia (Patreon), April 17, 2024, https://patreon.com/posts/when-genocide-is-102514539/.

- Sharon Zhang, “Journalism Professors: NYT Risks Credibility With Inaction on Oct. 7 Article,” TruthOut, April 29, 2024, https://truthout.org/articles/journalism-professors-nyt-risks-credibili….

- Susana Draper, Belén Marco, Ana María Morales, Sarah Ihmoud, Tara Alami, and Eman Ghanayem, “Palestinian Feminists Speak Out Against Reproductive Genocide,” TruthOut, May 15, 2024, https://truthout.org/articles/palestinian-feminists-speak-out-against-r….

- PFC, “The Palestinian Feminist Collective Condemns Reproductive Genocide in Gaza,” PFC website, February 10, 2024, https://palestinianfeministcollective.org/the-pfc-condemns-reproductive….

- Shelby Chestnut, “Trans Liberation and Palestine,” The Forge, June 21, 2024, https://forgeorganizing.org/article/trans-liberation-and-palestine/; Erin Allday, “Why trans activists are taking a leading role in pro-Palestinian protests,” SF Chronicle, May 15, 2024, https://sfchronicle.com/california/article/trans-activists-gaza-protest….

- Ghassan Bardawil, “Women’s Day under bombardment: A Feminist Call to Strike for Gaza and the decolonizing of International Women’s Day,” UCOS (website), March 8, 2024, https://ucos.be/iwd-gaza/.

- The phrase “invading socialist society” is a reference to a famous Black left-feminist text: C.L.R. James, F. Forest and Ria Stone, The Invading Socialist Society (London: Bedwick, 1972 [1947]). On “Ni Una Menos,” see the special section: “Transnational Feminist Strikes and Solidarities,” Critical Times 1(1): 146-148, 2018; on the transfeminist international, see: Anna Carastathis & Myrto Tsilimpounidi (eds.) Transfeminist International! (Athens: Feminist Autonomous Centre, 2023); on Jineolojî, see: Andrea Wolf Institute, “Urgent Call for Actions to Defend Rojava and to Build a Democratic Syria!,” Jineolojî, December 12, 2024, https://jineoloji.eu/en/2024/12/12/urgent-call-for-actions-to-defend-ro….