Ever since trans people became the U.S. Right’s punching target, the fervor has spread internationally. Why?

In The Global Fight Against LGBTI Rights: How Transnational Conservative Networks Target Sexual and Gender Minorities (NYU Press, 2024), political theorists Phillip M. Ayoub and Kristina Stoeckl demonstrate how fights over sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) rights are once again a popular unifier of what they call “moral conservative transnational advocacy networks” that frame LGBTI people as villains. They argue that “Moral conservatives construct their adversary by willfully misrepresenting the SOGI rights movement and transforming it into a symbol of everything else they reject: communism, global capitalism, liberalism, and international institutions.”1 PRA sat down to talk with Ayoub and Stoeckl about their research. They discuss the new strategies that LGBTI activists are using to combat growing authoritarian policies and laws that are opposed to SOGI rights. They also talk about how anti-trans and anti-LGBTI politics intertwine with issues like domestic violence and rights to abortion, gender identity expression, and marriage.

”Sexuality and gender-identity-based movements have always stoked opposition. But our book’s core argument is that some of those same transnational tools are being used to oppose LGBTI activist groups, by cross-border organizing.”

J. Gieseking: Can you tell our readers the core argument of your book and how you arrived there?

Phillip Ayoub: When Kristina and I met, we were thinking about how transnational tools were available to LGBTI and other progressive groups that diffuse rights initiatives to multiple places in a short period of time. Marriage equality and gender-identity policies are classic examples that have spread to different countries and continents around the same time.

Sexuality and gender-identity-based movements have always stoked opposition. But, in focusing on the last few decades, our book’s core argument is that some of those same transnational tools are being used to oppose LGBTI activist groups, by cross-border organizing. Venues like the UN, the European Union, and international courts are being used to wage [anti-SOGI rights] campaigns.

We observe that activist discourse and frames shared and diffused across borders also lead to the proliferation across borders of these moral conservative arguments and claims—whether it’s legislation like the so-called anti-gay propaganda policy or a concern like Drag Queen Story Hour becoming a panic in a few different countries.

“I realized that transnational networks influenced speaking about individual human rights in a particular way.”

Kristina Stoeckl: Around 2014–15, something very strange was happening in the Russian context. Being an Orthodox conservative was something to be vocalized and articulated with arguments that sounded completely new: to talk about traditional values, to prioritize the traditional family, to say that they are different from the West because they are for heterosexual unions and against abortion. Orthodoxy has always felt it’s very different from the West, but on different grounds. They would prioritize arguments like, we are more for the person, less for the individual; we are for the collective, less for the singular person; we are against enlightenment, for different forms of knowledge.

For a scholar of Orthodox Christianity studying a history that goes back a hundred years, that was bizarre. I realized that transnational networks influenced speaking about individual human rights in a particular way: books and pamphlets against abortion were being translated; NGOs were being created, modeled on the American A movement that emerged in the 1970s encompassing a wide swath of conservative Catholicism and Protestant evangelicalism. Learn more ; and NGO conferences were taking place, like the World Congress of Families.

“Human rights language is used to attack LGBTI rights by claiming that heterosexual people have to be protected from LGBTI rights.”

Gieseking: Let’s talk more about the mechanism and strategies used by the networks to oppose the rights of sexual and gender minorities. This going back and forth of ideas, tactics, organizations, and languages—is it all new?

Stoeckl: It’s not new in the American context, but it was in the European one. Human rights language is used to attack LGBTI rights by claiming that heterosexual people have to be protected from LGBTI rights.

Also, on a global scale, this use of human rights language was [now] proposed to be majoritarian. The Russian government was very effective in saying that they are the ones who defend traditional values and the understanding of human rights of the majority. They even cited Article 29 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which says that human rights have to be accorded with values in society, and the limitation clauses in the European Convention of Human Rights as evidence to say, we are actually the ones that propose a more original understanding of human rights, and there’s only a small, Western elite that is in favor of LGBTI rights.

“Moral conservatives often infringe on the human rights of LGBTI groups.”

Ayoub: There is a newness to this work across borders. Nations have often been opposed to gender and sexuality rights, namely to queer and trans communities gaining those rights, because of the fluidity around relationship models and gender identities that right-wing organizations sensed as disrupting the nation. Right-wing mobilizations were often deeply entrenched [in] The belief in the primacy of “the nation” as the most important political allegiance, that every nation should have its own state, and that it is the primary responsibility of the state and its leaders to preserve the nation. Learn more and a specific religious identity.

The willingness to cooperate across national divides and religious spaces to create a conservative coalition was hard to imagine 30 years ago. Then, [scholars and activists] didn’t think this kind of enthusiastic cross-border coordination was possible.

Moral conservatives often infringe on the human rights of LGBTI groups. They’re also using that human rights language and institutional framework willingly today. As a result, LGBTI groups have to rethink how they strategize and operate in transnational spaces. We use a metaphor [for this interactivity] in the book: a “double helix.” This changes the terrain of activism for both movements. It’s not the way that we thought of this in international relations before: that progressive groups in the international space target a certain country where they want to make changes and work with those activists; they hit opposition there in domestic space; and that country is compelled to change norms at some point, and that country’s opposition actors will come to change their mind. Instead, the opposition is everywhere.

“What’s interesting and controversial is that there are a lot of LGBTI campaigns using religious themes.”

Gieseking: Your book opens in Cyprus with local SOGI rights activists repurposing conservative rhetoric to proclaim, we are the family values campaign. Activists are forced into a search-engine-optimization of their language with profound implications. Can you give us some examples of this, and what are the promises and pitfalls of organizing using the same terminology as those who oppose our rights?

Ayoub: There’s a lot of debate about this within queer organizing: We are the family values campaign. Or: We are the children’s rights movement. What’s interesting and controversial is that there are a lot of LGBTI campaigns using religious themes. An example: LGBTI groups wanting to reconcile with the Catholic Church, [a campaign] where you see a handshake between an arm with a rosary and an arm with a rainbow wristband. But many groups say that they don’t want to reconcile with the Catholic Church—they have no interest in that because they feel like it’s not time to make peace.

Transnational activist spaces produce master frames that are implemented in different ways, including in domestic spaces. It’s important to highlight that they’re not attaching the same meaning to those words when they adopt the same language. They’re also not throwing out their past frames.

“There are also pitfalls for moral conservatives in organizing using the same terms.”

Stoeckl: There are also pitfalls for moral conservatives in organizing using the same terms. I call them “moral conservative readymades,” such as Christian Right groups and Orthodox moral conservatives using the same language, stories, and images as conservative Catholics, American evangelicals and Protestants, or Baptists from the Netherlands.

In the Russian Orthodox context around 2017, there was a debate about changing legislation on the decriminalization of domestic violence. Now we have a problem because we can no longer use the phrase “domestic violence” in Russia, which the Russian Orthodox Church blamed on foreign organizations, but in making that judgment it was itself influenced by a foreign organization, the World Congress of Families. Domestic violence comes out of an agenda that they would call the LGBT agenda, the gender agenda, that wants to destroy the family and that wants the state to play an active role inside the family. You cannot use the language of “gender” or “domestic violence.” In the end, the law to decriminalize acts of domestic violence passed. So that’s not only a problem on the side of progressive groups, it could also become a problem [for] moderate Christian groups.

“LGBTI organizing had rested on its laurels—at least in the transnational space—on the progressive recipe of global cosmopolitanism and human rights universalism.”

Gieseking: You outline how SOGI rights have become a target for right-wing organizing that claims to protect the nation, religion, children, women, the family, and society—a A term that describes someone whose gender identity matches the sex they were assigned at birth. Learn more and heteropatriarchal claim that reinforces dominant sexual and gender mores. What have been the most successful ways for organizers to intervene in this paternalistic ideology?

Ayoub: Some of this language is old and we see it being repackaged, especially in anti-trans organizing: This is against nature. This is against common sense.

LGBTI organizing had rested on its laurels—at least in the transnational space—on the progressive recipe of global cosmopolitanism and human rights universalism. It still works sometimes, but it comes with [limitations] in that LGBTI rights are deeply associated with the West.

Even though we’re talking about a transnational level, one of the strategies organizers are looking at now [is how] nation-states [rely on] national language. The logo for KPH (Polish Campaign against A form of heterosexism that devalues and scapegoats gay, lesbian, and bisexual people and people in same-gender relationships. Learn more ), the [country’s] main LGBT organization, [changed] to a logo that is the borders of the Polish nation. Organizers use Bible verses for an LGBT demonstration, like love thy neighbor, to show that everyone in this country knows this Bible verse in Catholic Poland. We want to show that this LGBT claim we’re making also connects to some of your existing religious or national values.

These geographic rooting frames try to reclaim some of those concepts, like nation, religion, and children. They point out that there are kids who are LGBTI who need protection. We have a major homelessness crisis around queer kids, [and many] queer children suffer from mental health issues, with very high rates of suicide. Some LGBT activists have said, no, actually, these children have rights; that they are the ones saving children with their activism and creating spaces for these children. Intersex activism, of course, is very much around children and the trauma that comes from unnecessary interventions.

“There’s a backlash against LGBTI rights in countries when EU accession is negotiated and where the European Union is presented as a promoter of LGBTI rights.”

Stoeckl: I would add here the long view we take on history: we do not start with the successes of LGBTI rights mobilization and the backlash that followed. We start earlier with the transnational Christian Right’s organizing against abortion.

It’s all one story and this is probably much clearer for people who oppose LGBTI rights than for those who support them. Trans rights are only the latest cherry they pick to make their point. It’s really tragic. The people who are targeted are singled out to make a point. They become a scapegoat for criticism of liberal democracy as a system.

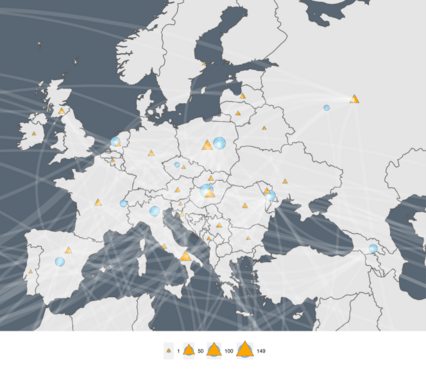

There’s a backlash against LGBTI rights in countries when EU accession is negotiated and where the European Union is presented as a promoter of LGBTI rights. Right-wing thinking starts from the idea that because the EU wants it, it’s amoral, and therefore they should turn to Russia instead of the EU.

Why is the EU being targeted? Detractors of the EU and the EU accession process single out SOGI rights because their countries have a long history of legislation against gay rights and it’s a very easy card to play. It’s clear that [this is happening] again in other EU candidate countries—Armenia, Moldova, Georgia, Ukraine before the war, and Serbia. The EU has done quite a lot on mainstreaming LGBTI rights. As part of its anti-discrimination directive, it protects people from The act of favoring members of one community/social identity over another, impacting health, prosperity, and political participation. Learn more based on sexual orientation and gender identity, and also age, origin, ethnic origin, disability.

“A lot of work was done to establish some core tenets of claims made by LGBTI people that have possibly become taken for granted among certain generations, regions, and/or countries.”

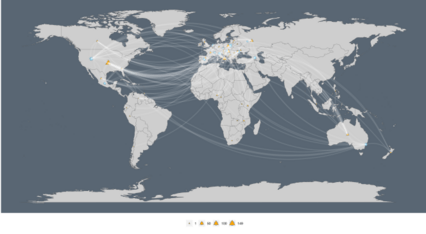

Gieseking: You put together detailed social network graphs of the wide array of right-wing transnational advocacy networks against SOGI rights. [See Figure 1 which depicts the flowmap of anti-SOGI transnational organizations, while Figure 2 zooms in on the European region.] As these networks continue to grow, what are your closing thoughts for A mass movement that seeks to transform society and challenge existing power relationships by means other than (but often including) the political electoral process. Learn more leaders about how to respond to and organize against networks like these?

Ayoub: Existing funding data shows how these networks are established and well resourced. They’re not going anywhere anytime soon. [Many] people find some of these moral conservative narratives compelling. We should take that very seriously as a movement. It’s not the case that a few LGBT rights have happened, and now we can enjoy this world. We have won it. [Conservative] actors in national campaigns have set their sights on doing this battle in other countries. Americans are still focused on Uganda and the wave of African countries that have been choosing these new, very restrictive death penalties, and criminalization of even simple expression that could be read as queer.

What is inspiring is the agility of LGBTI activists. They have had to rethink their strategies and move with intense opposition throughout history, since the 1800s or longer. A lot of work was done to establish some core tenets of claims made by LGBTI people that have possibly become taken for granted among certain generations, regions, and/or countries.

We [also] shouldn’t also lose sight of the more optimistic notes [of] how well LGBTI activists are organizing, because younger generations of queer people feel like they have a future and potential for the world to keep changing.

Figure 1: The global network of WCF organizing. (Credit: NYU Press)

Stoeckl: These global networks, like those depicted in the graphs, can also get broken. We saw how it happened several times in the World Congress of Families. It’s an organization where the Vatican was central, [then] it worked more intensively with Islamic countries. After 9/11, that [strategy] dropped out. That also happened with Russia’s attack on Ukraine: many of these active connections have been broken. But can they be reactivated?

It’s clear that a Global Right is using this group of people and the rights they are fighting for to change the world. I’m still optimistic that they won’t manage to do that. The problem, though, is they will find a new group, a new scapegoat, to push their policies.

Figure 2: A spotlight on Europe, a central home of WCF’s global organizing. (Credit: NYU Press)

Ayoub: There are qualitative differences between the two networks that we study, the LGBTI network and their opposition. There is literature, art, and stories of queer people finding togetherness across borders because they felt excluded in their own countries. This is a different pathway to global networks and collaboration among LGBTI activists that is thicker than these constructed networks for a given instrumental purpose. That qualitative difference is something also worth noting that gives me strength.