We have together, with the Protestants and the Catholics, enough votes to run the country. And when people say, “We’ve had enough,” we are going to take over.

—Pat Robertson

The Radical Mind: The Origins of Right-Wing Catholic and Protestant Coalition Building by Chelsea Ebin (University Press of Kansas, 2024)

Throughout the 1970s, White conservative Protestants (CPs) and Catholic New Right (CNR) political entrepreneurs were organizing on parallel tracks. As the decade drew to a close, both groups had identified the benefits of undertaking concerted political activism while also coming to recognize the limitations of their respective strategies. Independently of one another, each came to a point where they acknowledged the need for ecumenical coalition-building. On the CP side, this was facilitated by the development of the doctrine of co-belligerency. On the part of CNR activists, poor electoral returns created a new sense of urgency when it came to broadening their coalition. They just needed a consolidated discourse to knit together the plurality of issues that were, on one hand, galvanizing the Bible-believing grassroots and, on the other hand, promoted by the New Right. This discourse would center on the protection and preservation of the “traditional family.”

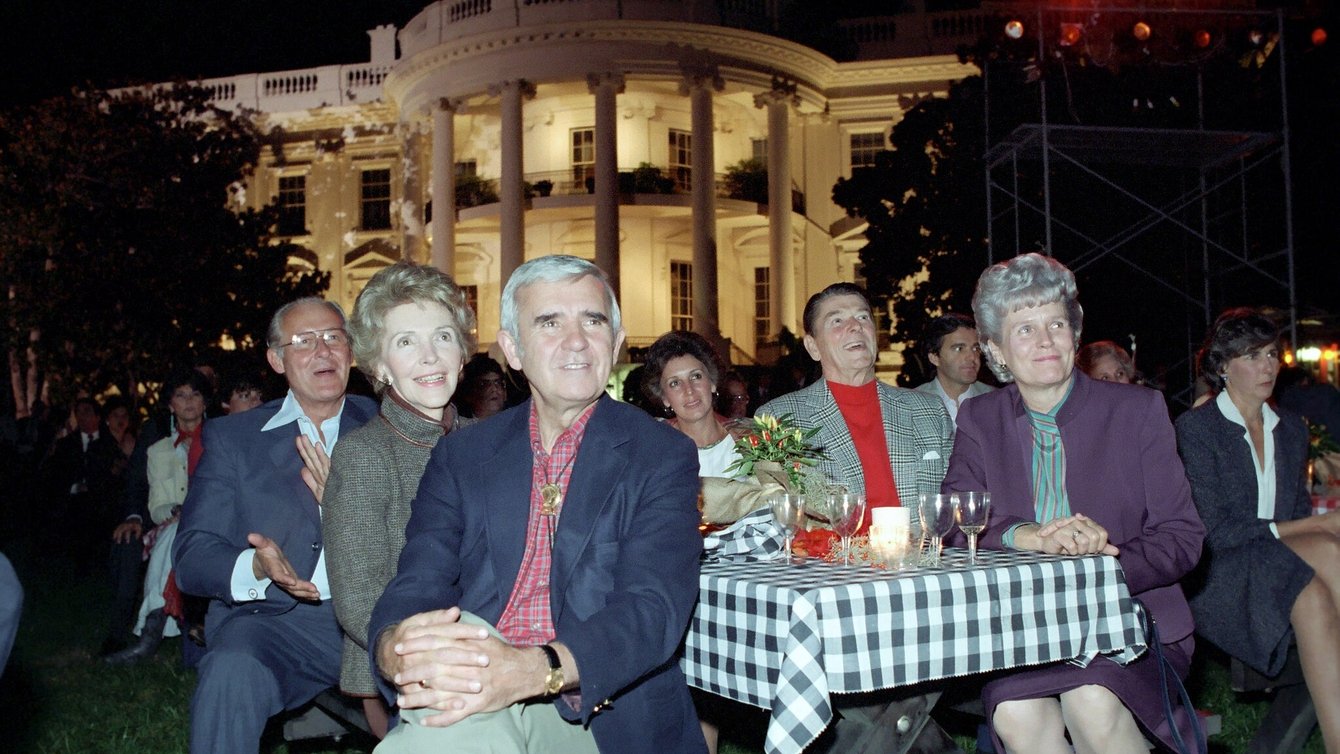

On October 1, 1980, the Reagan campaign formed a Family Policy Advisory Board (FPAB), chaired by [Catholic New Right activist] Connie Marshner and tasked with establishing a “pro-family” strategy for the Reagan campaign and, after November, the incoming Reagan administration. That fall, the FPAB advised Reagan on how to campaign on the “pro-family” platform, urging him to court segregation academy and Catholic votes by pressing tuition tax credits. Heritage Foundation co-founder Paul Weyrich also contributed to the effort, drafting a memo that urged Reagan to “unleash a strong attack on the White House Conference on Families,” which would be directed to a “grass-roots or religious audience, possibly in the south.”[1] Reagan nonetheless won over “pro-family” voters in November—and conservative Christians won over the Republican Party. By the fall of 1980, the New A movement that emerged in the 1970s encompassing a wide swath of conservative Catholicism and Protestant evangelicalism. Learn more had moved into the mainstream of American politics, with the process of incorporation into the Republican Party underway and the movement termed a “civil rights group,” at least in the conservative press.

“Originally introduced by the New Right Republican senator Paul Laxalt in 1979, the FPA thrust a deeply conservative interpretation of the ‘family’ into congressional political debate.”

Nonetheless, movement activists sought to keep the pressure on and pushed for the reintroduction and passage of the Family Protection Act (FPA), a bill that closely echoed family policy proposals first sketched by Marshner in 1974. Originally introduced by the New Right Republican senator Paul Laxalt in 1979, the FPA thrust a deeply conservative interpretation of the “family” into congressional political debate.[2] As reported by the Congressional Research Service, the legislation was divided into “six titles: 1) family preservation, 2) taxation, 3) education, 4) voluntary prayer and religious meditation, 5) rights of religious institutions and educational affiliates, and 6) miscellaneous.”[3] In a concept summary of the bill, produced by Senator Roger Jepsen’s office, the following core “pro-family” elements contained within Title I were highlighted:

Expansion and codification of parental rights as applied to determining the “religious and moral upbringing of their children”;

Parental notification requirement for minors receiving contraception or abortion services from any organization that receives federal funding;

Limits the power of the federal government and legislates the A power orientation that functions to maintain the relative power of some of the population, generally organized around race, ethnicity, gender, religion, or wealth. Learn more of state statutes in matters pertaining to juvenile delinquency, child abuse, and spousal abuse;

Prohibits the Legal Services Corporation from undertaking litigation in support of abortion, divorce, and homosexual rights;

Mandates automatic payment of “dependent’s allowance” for military personnel stationed away from their families;

Prohibits any federal funding for organizations that support gay rights.[4]

The bill’s other provisions were no less in line with the “pro-family” platform: Title II, concerning taxation, “would make it more difficult for the Internal Revenue Service to deny or revoke exemption of a private school on grounds of The act of favoring members of one community/social identity over another, impacting health, prosperity, and political participation. Learn more ,”[5] and aimed to amend the tax code to encourage “traditional” two-parent single-earner households by creating new tax-exemptions and deductions. Title III, focused on education reforms, would empower parents to have increased access to and influence over their children’s public education and limit the federal government’s power to regulate public education. Title IV would override the Supreme Court’s decision in Engle v. Vitale and reintroduce school prayer, while Title V would exempt religious organizations from federal oversight.

“By seeking to transform the relationship between the state and the family, the FPA aimed to comprehensively prefigure a new set of social relations on the basis of protecting the ‘traditional.’”

Were the Family Protection Act to be enacted into law, it would effectively redefine the family and the place of people of color, women, homosexuals, and children in society. The FPA would undermine desegregation efforts, weaken the federal government’s power to advance protections for historically underrepresented groups, and reassert the supremacy of (White) Christian men. Thus, the FPA was a comprehensive piece of legislation that sought to simultaneously limit the power of the state while also harnessing its coercive capacity to prescribe a particular set of social relations premised on the new definition of the “traditional” family.

While the “pro-family” movement used backlash discourse to define the movement as being on the defensive, its [policy strategy] was defined in terms of its proactive nature. The FPA and the “pro-family” platform promoted a comprehensive set of policies that would reach into all areas of Americans’ lives. Marshner was clear that “pro-family” issues were not isolated. Rather, the family was a conduit for attacking feminism, homosexuality, and desegregation, on one hand, and transforming public education, the tax code, welfare, and the criminal law, on the other hand. The family was also the basis for raising an army composed of Christian soldiers who would go forth and do battle for God.

By seeking to transform the relationship between the state and the family, the FPA aimed to comprehensively prefigure a new set of social relations on the basis of protecting the “traditional.” The policy changes it sought to produce would have defined new embodied roles for and relations between men, women, and children and restructured the ways in which individuals related to one another in both the public and private spheres. Through the imposition of these new embodied roles, the FPA further sought to entrench a hierarchical social order premised on conservative Christian ideals. Thus, the NCR did not merely want to stem the tide of cultural change; it wanted to reshape the country’s politics by proactively advancing policies that took aim at the very foundations of the liberal political order.

- Endnotes

- “Memorandum,” American Heritage Center, Box 19, Folder 13.

- “H.R. 7955 (96th): Family Protection Act,” GovTrack, 1980, accessed: January 2, 2017, https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/96/hr7955.

- Jan Fowler, “The Family Protection Act,” Congressional Research Service, July 20, 1981, WM, Box 79, FPA 81 Notes.

- Concept Summary, The Family Protection Act—97th Congress, Senator Jepsen’s office, AHC, Folder 13, Box 19.

- Jan Fowler, The Family Protection Act, Congressional Research Service, July 20, 1981, WM, Box 79, FPA 81 Notes.