On Saturday, December 12, dozens of members of the Generically used to describe factions of right-wing politics that are outside of and often critical of traditional conservatism. Learn more street gang the Proud Boys joined a pro-Trump demonstration in Washington, D.C. After listening for hours to speakers spreading conspiracy theories, as has happened at far-right rallies around the country since 2016, the Proud Boys led attacks on counter-protesters in what became a violent melee broadcast for the world on social media. While law enforcement around the country have spent the last several decades targeting Black and Brown youth for participation in what are often labeled as “gangs,” young White men joining similar groups have been largely left alone by gang task forces and police alike.

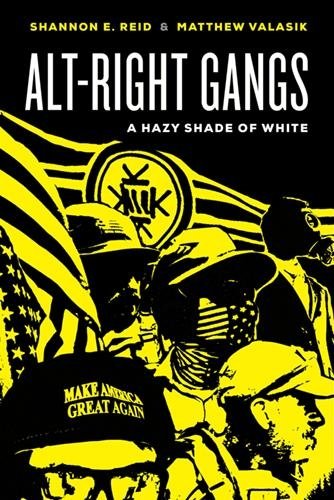

In a recent book by criminologists Shannon E. Reid and Matthew Valasik, A term from the 2010s to describe far-right activists rooted in paleoconservatism with more explicit racism & xenophobia. Learn more Gangs: A Hazy Shade of White (University of California Press, 2020), the authors pose an alternative approach to understanding violent White power groups ranging from the neonazi skinheads of the 1980s, to contemporary “Western Chauvinists” like the Proud Boys, to terrorist cells like Atomwaffen Division. The authors look at how these White power groups sometimes bond more over their willingness to engage in violence than their ideological unity. Within these communities, ideologies are less set in stone and more liable to change, particularly for younger members. Additionally, law enforcement seem less willing to intervene since they see groups like the Proud Boys as fundamentally different than those traditionally considered to be criminal or gangs.

This November, PRA talked with coauthor Shannon E. Reid about why groups like the Proud Boys have grown, the role violence serves in crafting their shared identity, and what the actual threat looks like on the ground.

White power groups sometimes bond more over their willingness to engage in violence than their ideological unity.

PRA: Why have Alt Right gangs like the Proud Boys grown so much in recent years?

Reid: After [California neonazi leader] Tom Metzger’s White Aryan Resistance [a White nationalist group known for recruiting young skinheads] got sued and the skinhead punk scene dried up and went more underground, I think it became harder for people to join those types of neonazi groups. But now with the Alt Right and Alt Lite, people like Richard Spencer, Milo Yiannopoulos, and Gavin McInnes were able to leave the internet and come back into the mainstream a bit. People like Donald Trump and Steve Bannon have fueled this, such as Trump’s comment [this September] for Proud Boys to “stand by,” which gives them mainstream credibility. If someone thought, “maybe these groups aren’t for me,” that rings as a pretty big endorsement.

For young White people, this new branding offers a way to be shocking and confrontational without having to commit to neonazi groups that might get them more obvious blowback from the community. It’s another avenue to kind of be part of a racist culture that maybe they didn’t feel like they could be part of before.

PRA: Why is the term “gang” important when talking about White nationalist and Alt Right groups?

Reid: A piece of this is that law enforcement often separates these Alt Right groups from how they think of street gangs because of their racist ideology. Just because they’re White and are loosely organized around this ideology doesn’t mean that that ideology usurps all the other behaviors, because it firstly assumes that they always adhere to this ideology. [The Proud Boys are a nominally multi-racial group and claim to oppose A social movement based on a belief in biologically determined racial hierarchies, often with the ultimate goal of establishing an all-White nation state. Learn more but are largely accused of fascist politics and racist associations.] It also assumes that “traditional” street gangs don’t have any ideological tenets, which they do. So the public just treats these “White” groups, which are engaging in the kind of violence law enforcement often ascribes to street gangs, as something fundamentally different than analogous groups from communities of color. And we’ve seen this dynamic with how Kyle Rittenhouse, the Kenosha shooter, has been handled. This illustrates how we treat people of color, particularly young males, so differently. So if the gang label is going to be used, it should be used to also include these White groups as well.

If the gang label is going to be used, it should be used to also include these White groups as well.

PRA: There’s been a lot of criticism leveled at law enforcement for their inability or unwillingness to respond to the violence from Alt Right groups. Why do you think that’s the case?

Reid: As we have seen from some of the research, there are officers who do not disagree with the statements these groups are making. And if you don’t disagree with them, your desire to intervene in a substantial way is minimized.

The other thing is that law enforcement is conditioned to see their enemy as Black and Brown people, and that “gangs” are groups of Black and Brown people. So I think that when it comes to these Alt Right groups, there’s this perception that these are groups of young people just trying to act out beliefs, and that ignores the actual behavior they are engaging in. But if groups of young people of color were engaging in the kind of behavior that Alt Right groups engage in, I cannot imagine the police would be responding the same way. If we think about things like stop-and-frisk and other police approaches, they are not equally distributed. The same thing happens here, where gang statutes and investigations are not being spread out equally.

These Alt Right groups are being treated like kids in a youth subculture finding their way, but we don’t treat young people of color like that; law enforcement will label them as a gang member forever. So, when we don’t equally distribute interventions, we perpetuate the same stereotypes and inequalities.

I do not believe that officers are unaware of who Proud Boys are in their communities, and what criminal behavior they are doing. I can guarantee that Proud Boys are doing other illegal things that are known to law enforcement, but they are not getting the kind of gang enhancements at sentencing that communities of color face.

These Alt Right groups are being treated like kids in a youth subculture finding their way, but we don’t treat young people of color like that; law enforcement will label them as a gang member forever.

PRA: How does violence act as a binding agent in the organization of these groups?

Reid: Violence is multi-level and it creates an in-group versus an out-group mentality. If you have ever listened to the way Gavin McInnes, founder of the Proud Boys, refers to it, while they don’t have a “jumping in” ceremony people may associate with skinhead gangs, they do have members participate in violence so that you know everyone who has been in a fight is “one of us.” To gain entry, to be in the “in-group,” you have to have been in the fight, particularly if it is with an individual affiliated with Antifa.

The commission of violence also adds to both their internal mythology and reputation and their external mythology. For example, in 2018 there was a fight outside of New York’s Metropolitan Republican Club involving the Proud Boys after Gavin McInnes had a speaking engagement there, and the story of that fight gets retold and becomes a bigger and bigger story. And this creates a mythology about the Proud Boys, so people who are outside the group and want to be inside the group begin to escalate their behavior so they can become members. This is why the “wannabes” in any subculture are always the most dangerous—because they want to impress established members. So the storytelling and mythology becomes something that helps build their identity and is sort of central to the in-group/out-group dynamic and group ethos that binds people together.

PRA: The Proud Boys work especially hard to portray themselves simply as a fraternal organization or a group of conservatives, often parroting conservative talking points in the media. Yet their actual behavior makes clear that they are much more radical. How is their internal ideology different from Beltway conservatism, and what kind of threat do they pose now?

Reid: Parts of the White power movement have learned the lesson that they can’t just have cross burnings and Klan hoods, because that is going to get them rejected. They have to use phrases like “Western Chauvinism” as a sort of dog-whistle. This includes their use of irony as a form of plausible deniability. When you talk to individual members, you actually see more extreme views, even when the organization presents itself as simply conservative. The very heteronormative, patriarchal, White power ideas are all still there, they’ve just done a better job of couching it in cleaner language to draw people in a little bit.

The threat they present is in the street-level violence they are causing. There is a day-to-day criminality these groups have. There are concerns about a potential civil war and people are sometimes waiting for the “big event” from the Far Right, but that kind of thing is rarer. The reality is that they are in communities right now and they are committing violence in those communities now. That is something we should focus on.