In late April 2020, Jessica Prim left her home in Peoria, Illinois, and headed east to New York Harbor, where the U.S. Navy Hospital Ship Comfort was docked. She arrived at midday on April 29. Although the Comfort was serving as a field hospital for COVID-19 patients, Prim was convinced it was holding so-called “mole children”: the rescued victims of a child sex-trafficking cabal lead by Democrats. Prim, who livestreamed her trip and part of her arrest, brought along 18 knives and promised to “take out” the cabal’s supposed leader, Hillary Clinton, and her “assistants,” Joe Biden and Tony Podesta.[1] When she was arrested, Prim told police that she felt that President Trump had been speaking directly to her at his coronavirus press conferences.[2] Journalists who combed Prim’s social media feed after her arrest found numerous references to the conspiracy theory turned mass delusion known as QAnon.

Although Democrats play villains in QAnon’s sex-trafficking conspiracy theory, the plot line closely follows an antisemitic myth from the Middle Ages, known as the Blood Libel,[3] which held that Jews killed Christian children and used their blood in religious ceremonies. Updated variants of the Blood Libel recur throughout history, but the QAnon version is especially dangerous because of its crowd-sourced character and lightening-quick diffusion. It combines discordant elements but papers over them with a stark hero/villain framing. And it is shared so widely on social media platforms (including Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, among others) that recipients don’t always know they’re reading verifiably false information.[4] Scholars with West Point’s Combatting Terrorism Center estimate that Prim made her trip to New York only 20 days after she first encountered QAnon misinformation online.[5]

The spread of QAnon conspiracy theories is also aided by elected officials in the Republican Party. This is striking given the party’s recent history. After World War II, Republican activists slowly pushed conspiracy theories to the margins of the party. The New Right political coalition that consolidated in the run-up to Ronald Reagan’s 1980 presidential campaign, for example, gained political power in part by expelling conspiratorial actors from the Republican Party, right-leaning think tanks, and conservative publications, and aggressively policing those who tried to reintroduce them.[6] And for 30 years that’s largely where they stayed. But today, the firewall between the Far Right[7] and mainstream conservatism is collapsing.

“Updated variants of the Blood Libel recur throughout history, but the QAnon version is especially dangerous because of its crowd-sourced character and lightening-quick diffusion.”

Given this shift, we were curious if conspiracy theories are now acting as a unifying force on the Right writ large, allowing groups that are operationally independent and ideologically suspicious of one another to bang the same rhetorical drum. A conspiracy-based coalition that brings Generically used to describe factions of right-wing politics that are outside of and often critical of traditional conservatism. Learn more and mainstream operators together could create a cohesive counter-narrative about power in the U.S. that is bigger than the sum of its parts.

To explore the possibility, we mapped a QAnon Facebook network, looking at what misinformation was shared and what other actors in the Facebook universe were sharing the same content. This allowed us to identify which groups along the right-wing spectrum were connected through conspiracist thought. We chose late April 2020, a time when far-right activity was heating up across the spectrum, from Prim’s QAnon-inspired trip to New York City to widespread protests against COVID-related lockdowns.

The QAnon network we mapped was large, dense, and politically aligned with President Trump and other mainstream[8] right-wing actors. It also had a sizeable international component, with groups based in Africa, Asia, Eurasia, and Latin America.[9]

Unsurprisingly, the network’s dominant narrative focused on the “Deep State.” There is no one definition of the “Deep State,” of course. In emerging democracies, or semi-authoritarian regimes, the term often refers to private forces that hold sway over government actions (such as narco-trafficking groups in Mexico or crime syndicates in Turkey).[10] Trump often used the term in reference to holdovers from the Obama administration, whom he accused of trying to derail his presidency.[11] QAnon’s definition is broader, emphasizing global elites who want to undermine American power and control its citizens, but leaving open who these elites are, from civil servants to billionaires, with little distinction as to nationality. Bill Gates (born in the U.S.) and George Soros (a native of Hungary) are both frequent targets. The definition’s emphasis on unchecked power is also general enough to resonate with ideologies across the Right, from mainstream complaints about China as a world power to far-right suspicions of government overreach.

“QAnon’s definition is broader, emphasizing global elites who want to undermine American power and control its citizens, but leaving open who these elites are, from civil servants to billionaires, with little distinction as to nationality.”

Connective Tissue for a Fractious Right?

Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential run sparked a resurgence of far-right activism in the U.S. For many far-right groups, Trump was something of a political unicorn—a presidential candidate they actually liked and wanted to support. As the Anti-Defamation League’s Mark Pitcavage explains with reference to the militia movement, “He was the first major party candidate they had ever supported who got elected…they were quite jubilant when he won.”[12]

Despite the upsurge, the various groups that comprise the Far Right historically have shown little appetite or ability to work together. A primary obstacle to far-right unity is ideology, and what that means for enemy identification. White supremacists point primarily to Black and Hispanic Americans. Neonazis believe Jews are the enemy. Other groups, like the Proud Boys, see “Antifa” as their main threat.[13] Far-right groups also differ on how they view the role of government. Traditional militias[14] believe that the federal government is dangerous, no matter which party is in power. Some White nationalists, by contrast, support a strong federal government, so long as it is run by and for White people.

While An aggravated form of sexism that is a primary motivation for the Right, both as recruitment for and justification of its agenda. Learn more is common across the Far Right, there are also disagreements about the role women should play in achieving movement goals. Militia groups usually welcome women into their ranks, though they’re often assigned to administrative roles,[15] while the Proud Boys think women should be housewives and leave the fighting to men.[16] For their part, incels (involuntary celibates)[17] are deeply suspicious of women, with some even supporting violence against women who refuse to have sex with them.[18]

Recent attempts to unify groups on the Far Right have also failed. The 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, is a case in point. The rally was organized by Jason Kessler and Richard Spencer to bring together White nationalists, neonazis, neo-Confederates, and militia groups, but after a rally goer killed counter-protester Heather Heyer, the finger pointing began.[19] A few days after the event, the leader of one militia group that attended the rally distanced his group from the rally’s organizers, calling Kessler a “piece of shit” and a “dirtbag.”[20]

These divides dilute the power of the Far Right today. However, Trump’s popularity among them, and conspiracy theories designed to defend and lionize him, have the potential to bring far-right and mainstream operators into rhetorical sync. Even if these groups disagree on ideology, strategy, and tactics, broad acceptance of misinformation on one half of the political spectrum represents a real threat to American democracy.

Stop the Steal Rally at St. Paul, Minnesota on January 6th 2020. (Credit: Chad Davis/Flickr)

What Makes Something a Conspiracy Theory?

In its simplest form, a conspiracy is a “secret plot by two or more powerful actors.” Some conspiracies are criminal, designed to break a law (two people conspiring to rob a bank), while others are political, meant to undermine powerful people, organizations, or even states.[21] In politics, the word conspiracy is often shorthand for fanciful or far-fetched explanations, but of course, some conspiracies are true. In the social sciences, the term “conspiracy theory” is typically used for an alleged conspiracy that is patently false, or for which there is sparse or unconvincing evidence.[22]

Conspiracy theories often question the narratives that powerful people use to explain or justify their actions. They are divisive by design. As far-right expert Chip Berlet explains,[23] conspiracy theories tend to divide the world into a besieged “us” and a threatening “them”—frequently an otherized group such as immigrants, homeless people, or racial, religious, and sexual minorities. Not surprisingly, calls to action are often cast in do-or-die terms.

Many political conspiracy theories are broad by design. At the individual level they allow people to connect the actions of distant power brokers to their everyday, lived experiences.

Why people believe conspiracy theories is the subject of debate, but at a macro level, conspiracy theories are manifestations of adherents’ worries, fears, and lived experiences. As Jesse Walker, author of the 2013 book The United States of Paranoia: A Conspiracy Theory, explains, a conspiracy theory “says something true about the anxieties and experiences of the people who believe and repeat it, even if it says nothing true about the objects of the theory itself.”[24]

Right-Wing Conspiracy Theories Since 1970

In 1964 historian Richard Hofstadter coined the term “the paranoid style”[25] to describe what he saw as a propensity towards conspiratorial thinking on the fringes of U.S. politics. People who study conspiracy theories take issue with Hofstadter’s assessment that conspiracies are just a fringe phenomenon.[26] They also note that the post-war liberal consensus that allowed people on both sides of the aisle to agree on what was and wasn’t a conspiracy theory has eroded (if it ever existed at all).[27]

However, Hofstadter’s assumption of a stable middle ground is useful for understanding how conspiratorial views were relegated to the margins of the Political Right after World War II. After the war, far-right groups had considerable sway in the Republican Party. Initially, they trained their ire on Roosevelt’s New Deal program. Friedrich Hayek’s book, The Road to Serfdom, for example, described the New Deal as the first step towards government bondage, and provided bones onto which right-wing conspiracists could add flesh. As the Cold War progressed, right-wing conspiracists pointed to a new antagonist—“cosmopolitan”[28] leftists. Wrapping an American flag around antisemitic and anti-elitist sentiments, they promised to rid the U.S. of its internal enemies.

Senator Joseph McCarthy’s Red Scare is a case in point. The ostensible targets of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) were Communists, for example, but Jews were disproportionately affected.[29] The actors, directors, and screenwriters hauled before the committee were depicted (using age-old antisemitic tropes) as having divided loyalties and being in cahoots with foreign governments. Republicans ended the Red Scare with a black eye. Senator McCarthy was formally censured by the Senate, and the party’s unity was unnecessarily frayed. Young conservatives took note: A mode of political explanation that assumes a vast insidious plot against the common good. Learn more didn’t pay.

“As the Cold War progressed, right-wing conspiracists pointed to a new protagonist—’cosmopolitan’ leftists. Wrapping an American flag around antisemitic and anti-elitist sentiments, they promised to rid the U.S. of its internal enemies.”

The rebirth of the Right that began in earnest after the Red Scare rested on two pillars: marginalizing conspiratorial-minded groups, and building a new coalition of evangelicals, big business, and neoconservatives. Early leaders in this nascent coalition, which would come to be known as the New Right, believed conspiracy theories would doom Republican chances at the ballot box. The Right had to fight the Left with ideas, not convoluted stories with muddled plotlines. As New Right historian Sara Diamond notes, the New Right started as an intellectual movement and morphed into a social one.[30] William F. Buckley led the charge. In 1964 he used his perch as editor at National Review to excoriate the John Birch Society’s founder Robert Welch, convincing Welch’s supporters, most notably Barry Goldwater, to push the organization out of the Republican fold.[31] So-called neoconservatives, many of whom were Jewish, also refused to countenance explicit A form of oppression targeting Jews and those perceived to be Jewish, including bigoted speech, violent acts, and discriminatory policy. Learn more in the party.[32] By the 1970s, conspiracies had been largely pushed aside.

Conspiracies continued to circulate on the fringe, however, and echoed the old Right’s isolationism and antisemitism. The most influential was the Zionist Occupied Government (ZOG). ZOG was an Americanized version of a conspiracy that began in Czarist Russia with the publication of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion—the notorious forgery, purportedly written by Jewish leaders, describing efforts to manipulate countries across the globe.[33] The book was a hoax, but it was reprinted in multiple languages—including, in the U.S., by Henry Ford—used to justify pogroms in Russia and Eastern Europe, and later deployed to support A form of fascism developed by Adolf Hitler’s National Socialist German Workers Party (Nazi Party) and the state it controlled in Germany and other parts of occupied Europe from 1933 to 1945. Learn more .

Although ZOG predated the rise of the U.S. militia movement, in the 1980s and ‘90s, these groups updated the theory for their own purposes. This time their target was the “New World Order” (NWO), a change that provided some rhetorical distance from antisemitism. They also referred to its presumed leaders as “bankers” or “global elites” instead of “Jews” and “Zionists.” And they shifted their attention from banks to international organizations, arguing that U.S. leaders were using groups like the United Nations and multilateral trade pacts like the North American Free Trade Agreement to undermine American economic dominance and pave the way for occupation by UN troops.

The NWO resonated in and beyond the militia movement because it reframed the ZOG conspiracy theory for America’s postindustrial landscape, providing an explanation for why politicians signed trade deals that cost U.S. jobs and devastated local communities.[34] The conspiracy theory was also broad enough to justify opposition to the ongoing paramilitarization of federal police, which began before 9/11 but ramped up considerably in its wake.[35] Federal sieges in Waco, Texas, and Ruby Ridge, Idaho, were held up as evidence that the NWO was preparing for imminent takeover and would soon seize law-abiding citizens’ guns.

The 1990s also saw the rise of related conspiracy theories, including the Plan de Aztlan and its later spin-off, the North American Union (NAU).[36] The first theory posited that Mexican Americans were working with Mexico’s government to recapture Southwestern territories that once had been Mexican. The second contended that then-Presidents Vincente Fox and George W. Bush were plotting to combine Mexico, the U.S., and Canada into a single nation. Although the actors were different, the presumed goal was similar to that posited in the NWO: global elites scheming to undermine U.S. sovereignty.

Although the New Right coalition had purposefully marginalized conspiratorial voices, by the late ‘90s, these conspiracies began to slowly creep into the mainstream Right. After the Waco and Ruby Ridge sieges, for example, then-Republican congresswoman Helen Chenoweth (R-ID) held hearings about alleged sightings of black helicopters, which militia groups believe are owned/controlled by the UN.[37] In the early 2000s, Republican congressmen Tom Tancredo (R-CO) and Virgil Goode (R-VA) publicly expressed belief in the North American Union conspiracy theory.[38]

The seep of conspiratorial thinking into the mainstream Right accelerated with the growth of the Tea Party after the 2008 recession. While initial Tea Party groups were focused on opposition to the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) signed into law by George Bush and continued by Barack Obama,[39] many local affiliates were quickly overtaken by activists aligned with U.S. militias, Christian Dominionists, and ethnonationalists.[40] These groups’ focus shifted the movement towards anti-government conspiracism, presaging the rise of “Deep State” rhetoric that would catch fire a decade later. Surprisingly, though the term was popularized in 2014 by a Republican staffer and Tea Party critic,[41] it only entered mainstream discourse after Trump used it to label his enemies, and QAnon and other far-right groups amplified it across social media.

Proud Boys Rally, 12 December, 2020 (Credit: Elvert Barnes/Wikimedia Commons)

Mapping the Network

A network, defined most basically, is a collection of people who interact with one another around a common purpose or point of interest. Like a high school, not everyone in a network knows each other, but they tend to share the same information. Also like schools, networks have a pecking order. Dominant actors—the cool kids of the network—establish priorities and a sense of what is important, and have the largest platforms for communicating those ideas. Networks also have key conduits that keep different parts of the network connected—like meme-sharing accounts that unite mainstream Republican groups with far-right, international, and even Leftist groups.

We chose QAnon as our focus because of its dominance in the conspiracist marketplace. No one knows exactly when QAnon began, but its preeminent origin story[42] suggests it was born on October 30, 2017, when an anonymous poster named Q claimed Hillary Clinton would be arrested later that afternoon. Q’s prediction proved incorrect, but the account won a following by claiming to have a high-level security clearance (level Q in the Department of Energy) and personal knowledge of Deep State operatives. Today, QAnon is associated with hundreds of unique conspiracies about topics as diverse as so-called “mole children,” vaccines, and Central American refugees.[43]

QAnon’s dominance is due in part to its structure as a participatory, crowdsourced initiative. Although Q periodically drops hints (so called breadcrumbs or “Q-drops”), adherents are encouraged to “do their own research.”[44] This allows ordinary users to shape conspiracies as they see fit. Q’s suspicion of the federal government also allows its conspiracy theories to resonate with militias, sovereign citizens, and Trump supporters. Likewise, its underlying antisemitism, A form of heterosexism that devalues and scapegoats gay, lesbian, and bisexual people and people in same-gender relationships. Learn more , and An ideology that assumes a hierarchy of human worth based on the social construction of racial difference. Racism as an ideology claims superiority of the socially constructed category, White, over other racialized categories based on the false idea that race is a fixed and immutable reality. Learn more allow it to connect to neonazis and White nationalists. But the often-coded language also means many people who interface with QAnon conspiracy theories have little idea of the ideologies of hate and extremism that underlie them; many don’t even know they’re reading QAnon material.

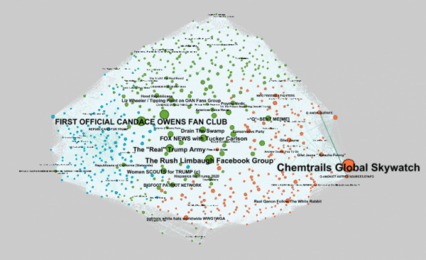

For our analysis we mapped[45] the social network of QAnon Facebook groups during mid-April 2020, when anti-lockdown protests were occurring across the country. Our goal was to find out how big the network was, how dense it was, and what its dominant groups were. We also wanted to know what they shared with each other.

Networks can be defined by place, theme, or through evidence of coordination, such as users who share the same posts or use the same hashtags. We looked at the latter, specifically using coordinated link-sharing behavior—in layman’s terms, links that get shared by multiple actors in a network within a narrow time frame.[46] This behavior allows network members to quickly establish a driving narrative about something and reinforce it through repetition, ensuring not only that more people will see the chosen narrative, but also that they’re less likely to see something else. It also offers the illusion of grassroots momentum: fostering the sense that a particular post—and the narrative it’s advancing—gained prominence organically. For these reasons, studying link-sharing in the QAnon Facebook network provides a valuable window into how different segments of the Right have built a rhetorical coalition around the “Deep State” conspiracy theory.

Q Lockdown Network

Network Structure

Our first step was to select Facebook groups associated with QAnon. We settled on 23 groups,[47] with a combined membership of 387,416 accounts. We then extracted all of these groups’ posts with links during the week of April 14, 2020, when anti-lockdown protests were in high gear. Finally, we looked[48] for other Facebook groups—of any type—that shared the same links within six seconds. These groups constituted our “Q Lockdown” network.

The network we mapped was very large—it contained 6,872 distinct Facebook groups, 369.5 million accounts,[49] and 1.2 million connections (i.e. the total number of connections between groups in the network). When we filtered out[50] groups that have relatively few connections with other members of the network, we were left with a core of 623 groups, 51.4 million accounts, and 95,000 connections between them.

The core of the Q Lockdown network was dense, with 95,132 connections between groups, accounting for nearly half of all possible connections.[51] Dense networks are ideal for spreading misinformation, because if a few groups are removed from the network (e.g. for violating Facebook policies), there are still plenty of other connections in place to circulate information across the network.

The network’s membership was also notably partisan, with almost half the core groups defining themselves in political terms, citing “Trump,” “MAGA,” “drain the swamp,” or other conservative terminology in their names. By contrast, only four percent of groups had names that aligned with Patriot or militia ideology,[52] and many of which referenced Trump in their name.[53]

Partisan groups were also the network’s key actors. Eight of the top-10 link-sharing groups were Trump-aligned or clearly conservative,[54] as were nine of the 10 groups that had the most direct connections with other groups in the network.[55] These findings suggest that the content QAnon is sharing is not a fringe phenomenon, but a thoroughly mainstream one.

In other words, QAnon conspiracy theories aren’t seeping into the mainstream; rather, they start there. And they are spreading internationally, as 20 percent of the core Q Lockdown network was comprised of international groups.

Network mapping was done using Gephi.

The Conspiracy Theories They Shared

We also analyzed the top 50 links shared by Q Lockdown network[56] to see if any key themes or patterns emerged. No one story or issue dominated the top 50 posts, but we found that the Deep State was the network’s primary concern. Many of their posts included tropes common in previous eras of anti-government conspiracism, including global puppet masters, international bad will towards the U.S., and domestic enablers of U.S. decline.

The puppet master role was filled by Bill Gates, the founder of Microsoft and a current philanthropist focused on public health. In the eighth-most shared link, a video of a livestreamed anti-lockdown protest, Gates was described as a “master psychopath that wants to kill [us] all.” Gates’s name also came up in a conspiratorial video that suggested he wanted to use COVID-19 vaccinations to implant tracking devices in Americans.[57] This conspiracy has become one of the most enduring of COVID-19 and is a potential public health nightmare as individuals worried about government surveillance vow to refuse vaccinations. Other stories included a Washington Post article that raised questions about the hacking of 25,000 email addresses and passwords from the Gates Foundation, the National Institute of Health, and the World Health Organization.[58]

“In other words, QAnon conspiracy theories aren’t seeping into the mainstream; rather, they start there. And they are spreading internationally, as 20 percent of the core Q Lockdown network was comprised of international groups.”

China played the role of malevolent international actor. The top-shared links that mentioned China were usually from conservative outlets, such as Fox News or the UK’s Express News, TV personalities such as Glenn Beck, or Trump-aligned politicians such as Rep. Dan Crenshaw (R-TX). Most links accused China of either intentionally creating the COVID-19 virus in a lab, or accidentally doing so and then trying to cover its tracks. Although scientists believe the virus moved to humans naturally, almost 30 percent of Americans surveyed in April believed COVID-19 was created in a lab.[59] Links pushed by QAnon actors are helping to keep this conspiracy alive.

U.S. mayors and governors were often depicted as stooges, allowing Gates, Democrats, and even China to use COVID-19 as an excuse to tighten their grip on the population. In one video link, for example, Trump supporter Candace Owens likens being forced to wear a mask in Whole Foods to tyranny. Another top-50 link to an NPR article quoted Attorney General Barr promising to take steps to curtail governors’ public health restrictions “if we think one goes too far” or became “burdens on civil liberties.”

After the Election

Given the fact that most states eventually loosened public health restrictions, we wanted to assess whether any of the Facebook groups in our Q Lockdown network moved on to another conspiracy—namely, President Trump’s baseless claims of election fraud. This could demonstrate whether the network came together specifically around pandemic-related issues, or if QAnon conspiracism is sticky enough to draw together disparate right-wing groups around other Deep State themes as well.

To answer our question, we downloaded the names of all Facebook groups who used the hashtag #stopthesteal just before and after the election.[60] We found that 14 percent of the network’s core groups had also spread conspiracy theories about the election, including four groups[61] that are among the lockdown network’s most dominant actors.[62] This suggests that support for Donald Trump is a central feature of QAnon followers. Further, these groups are well placed to spread disinformation across the entire right of the political spectrum, uniting otherwise fractious right-wing groups. Finally, it’s worth noting that this core network of disinformation spreaders remained intact even after multiple Facebook purges of QAnon groups.

Are we in a Post-Truth World?

Richard Hofstadter’s critics were right to call into question his claim that conspiracy theories only exist on the fringes of American life. After all, nearly 10 percent of Americans still don’t believe we landed on the moon,[63] and so many people refuse to believe Elvis Presley is dead that Wikipedia has a page devoted to Elvis sightings since his death.[64] But when we focus on the political sphere, Hofstadter’s underlying assumption, that conspiracy theories thrive on the fringes because there exists a stable middle ready to reject them, isn’t as off-base as some have suggested.

The New Right political coalition did effectively banish far-right conspiracy theories to the margins of their movement in the 1970s. That, in turn, allowed Republicans to participate in democratic government, not because they agreed with their Democratic rivals’ ideology or policies, but because they held democratic principles in common and followed the same political rulebook. None of this is to romanticize the New Right coalition—conspiratorial voices were always present and sometimes indulged. Pat Buchanan was a frequent Republican pundit on Sunday news shows well into the 2000s, even though he was also one of the GOP’s leading conspiracy theorists. But he was never able to break into the top tier of the party. Indeed, after he failed to win his Republican presidential primary campaigns in 1992 and 1996, he left the party for his third try in 2000.[65] However imperfect, GOP efforts to relegate conspiracism to the fringes worked for decades.

“Instead, even though QAnon’s main goal feels mostly apolitical—designed to sow chaos and defend the capricious interests of one man—it has become synonymous with a major political party.”

Today, the democratic consensus is in tatters. This consensus wouldn’t have stopped QAnon conspiracies from emerging and spreading, but it would have kept them out of government. Instead, even though QAnon’s main goal feels mostly apolitical—designed to sow chaos and defend the capricious interests of one man—it has become synonymous with a major political party. It is ironic that the party that once decried moral relativism is now firmly in its thrall.

This shift also puts far-right and mainstream operators into similar discursive space. Although we only found a small percentage of groups with names specifically aligned with militias or other far-right groups, their conspiracy theories—about a tyrannical federal government and the traitorous elites—are now front and center in QAnon-inflected mainstream discourse.

But even if we can’t agree on what it is these days, truth has consequences. When Americans think vaccines are embedded with microchips, too many of them will refuse to take them. If they believe Central American refugees fleeing violence are Soros-funded agents provocateurs, they will villainize and dehumanize them. And when ordinary citizens think Democrats are running a pedophile ring, they will continue to show up at pizza parlors,[66] Navy ships, and any number of other places, armed and ready to fight.

By giving QAnon groups space on its platform, Facebook has contributed to the erosion of the most precious resource in any democracy: a shared consensus on what is true, right, and decent. Despite Facebook’s promise to tackle disinformation, its focus on sporadic removals of groups for repeated content violations as opposed to outright movement bans gives members the chance to turn to back-up accounts, create new groups, and continue to thrive.[67] And Facebook’s lax approach means QAnon groups can evade purge detection by continually changing their names to more neutral-sounding titles such as news organizations, celebrities, or even children’s movies.[68] Not surprisingly, many of the actors in our initial Q Lockdown network study survived Facebook’s summer purges, and went on to spread lies about the 2020 presidential election.

It’s worth noting that, by early January 2021, 22 of the 23 QAnon groups used in our initial list were removed from Facebook. However, while the explicitly Q-focused pages were taken down, mainstream accounts such as Fox News, Candace Owens, and Trump supporting groups remained, circulating disinformation behind a veil of normalcy. This reality of conspiratorial narratives flooding mainstream discourse makes stemming their flow all the more difficult.

Facebook’s failure to rein in misinformation is even more frightening when we consider the international composition of the Q Lockdown network we mapped. QAnon is creating a global following for far-fetched conspiracies that breed resentment, erode trust, and sow confusion. Tackling global problems—and there are plenty of them—will be harder as a result.

- Endnotes

[1] Ben Yakas, “QAnon Believer Arrested In Manhattan Carrying 18 Knives After Allegedly Threatening Joe Biden & Hillary Clinton,” Gothamist, April 30, 2020, https://gothamist.com/news/qanon-believer-arrested-manhattan-carrying-18-knives-after-allegedly-threatening-joe-biden-hillary-clinton.

[2] Will Sommer, “A Qanon Devotee live streamed her trip to New York to take out Joe Biden,” The Daily Beast, April 30, 2020, https://www.thedailybeast.com/a-qanon-devotee-live-streamed-her-trip-to-ny-to-take-out-joe-biden?ref=scroll.

[3] Southern Poverty Law Center, “What you need to know About QAnon,” October 27, 2020, https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/2020/10/27/what-you-need-know-about-qanon.

[4] Jaclyn Fox, “How QAnon Hijacked #SaveTheChildren To Grow Their Following,” Rantt Media, November 27, 2020, https://rantt.com/qanon-hijacked-savethechildren.

[5] Amarnath Amarasingam and Marc-Andre Argentino, “The QAnon Conspiracy Theory: A Security Threat in the Making?” CTC Sentinel, Volume 13, Issue 7, https://ctc.usma.edu/the-qanon-conspiracy-theory-a-security-threat-in-the-making/.

[6] Sara Diamond, Roads to Dominion: Right-wing Movements and Political Power in the United States, 1995. Guilford Press, pp. 12-16, and 151.

[7] We define the Far Right broadly to include hate groups as well as A generic category for anyone who holds beliefs outside of those approved by mainstream or broadly centrist preferences. Learn more groups not motivated primarily by hate (e.g. militias). See: Southern Poverty Law Center, “Hate and Extremism,” 2020, https://www.splcenter.org/issues/hat e-and-extremism.

[8] Although many people do not consider Donald Trump a mainstream figure, we define mainstream here in institutional, rather than ideological terms. Key mainstream political institutions—the Republican Party, right-wing think tanks, and Fox New—are now firmly in Trump’s orbit.

[9] We define a group as international if its name was in a foreign language (e.g. ওয়াশিংটনডিসির খবর ,马六甲吹水站, Српско-руско братство - духовно и историјско, דר גיא בכור מזרחן ומרצה .מזרח התיכון ) or included a foreign country in its name (e.g. The Dutch Resistance, The Official Guyanese Page, CYPRUS FREEDOM, Ugandans in Dubai & UAE).

[10] Rebecca Gordon, “What the American ‘deep state’ actually is, and why Trump gets it wrong,” Business Insider, 27 January 2020, https://www.businessinsider.com/what-deep-state-is-and-why-trump-gets-it-wrong-2020-1.

[11] Michael Crowley, “The Deep State is Real, but It Might not be What You Think,” Politico Magazine, September/October 2017, https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2017/09/05/deep-state-real-cia-….

[12] Kim Strong, “Militias say they protect rights, critics call it a sham,” York Daily Record, September 12, 2020, September 12, 2020, https://apnews.com/article/constitutions-pennsylvania-gettysburg-gun-po….

[13] “The Proud Boys,” Anti-Defamation League, 2020, https://www.adl.org/proudboys.

[14] Newer militia groups, including the Oath Keepers and the III%ers, are less suspicious of the federal government. They cheered then-President Trump’s aggressive use of federal policing against refugees crossing the southern border and protestors around George Floyd’s murder in cities like Portland. For more information on divides in the current militia movement see: Jaclyn Fox and Carolyn Gallaher, “Could Anti-government Militias become Pro-state Paramilitaries,” The Public Eye, Fall 2020, https://www.politicalresearch.org/2020/10/27/could-anti-government-militias-become-pro-state-paramilitaries.

[15] Gina Terinoni, “Women of the contemporary Militia Movement: Perceptions of ideology through experience identity voice and action,” 1997. Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5239. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5239.

[16] Ed Mazza, “Gavin McInnes, Fox News Guest, Says Women Are ‘Less Ambitious’ And ‘Happier At Home,’” Huffpost, May 15, 2015, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/gavin-mcinnes-women-happier-at-home_n_72….

[17] Roberta Ligget O’Malley, Karen Holt, and Thomas J. Holt, “An Exploration of the Involuntary Celibate (Incel) Subculture Online,” Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 2020 Sep 24, doi: 10.1177/0886260520959625.

[18] “Incels (Involuntary Celibates),” Anti-Defamation League, https://www.adl.org/resources/backgrounders/incels-involuntary-celibates.

[19] Ben Lorber, “‘America First Is Inevitable’ Nick Fuentes, the Groyper Army, and the Mainstreaming of A social movement based on a belief in biologically determined racial hierarchies, often with the ultimate goal of establishing an all-White nation state. Learn more ,” Political Research Associates, January 15, 2021, https://www.politicalresearch.org/2021/01/15/america-first-inevitable.

[20] Matthew Santoni, “New Derry man who led militia in Charlottesville clash condemns white supremacists,” TribLive, August 14, 2017, https://archive.triblive.com/local/westmoreland/new-derry-man-who-led-militia-in-charlottesville-clash-condemns-white-supremacists/.

[21] Karen M. Douglas, Joseph E. Uscinski, Robbie M. Sutton, Aleksandra Cichocka, Turkay Nefes, Chee Siang Ang, Kent Farzin Deravi, “Understanding Conspiracy Theories,” Advances in Political Psychology, Vol. 40, Suppl. 1, 2019. doi: 10.1111/pops.12568.

[22] “Conspiracy Theory,” Anti-Defamation League, 2020, https://www.adl.org/resources/glossary-terms/conspiracy-theory.

[23] Chip Berlet, “ZOG Ate My Brain,” New Internationalist, October 2, 2004 https://newint.org/features/2004/10/01/conspiracism.

[24] Jesse Walker, The United States of Paranoia: A Conspiracy Theory, Harper Perenniel, reprint, 2014, p. 15.

[25] Richard Hofstadter, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” Harper’s Magazine, November 1964, https://harpers.org/archive/1964/11/the-paranoid-style-in-american-politics/.

[26] Jesse Walker, The United States of Paranoia, chapter 1.

[27] Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Michele Aina Barale, Jonathan Goldberg, and Michale Moon. 2002. Touch Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity. Duke University Press, 142.

[28] See Cathy Gelbin and Sander Gelman. Cosmopolitanisms and the Jews, 2017. University of Michigan Press, for a detailed review of the way the term cosmopolitanism was used to mark Jews as foreign, deviant, and dangerous in various locations and time periods.

[29] Joseph Litvak, The Un-Americans: Jews, the Blacklist, and Stoolpigeon Culture, Duke University Press, 2009

[30] Sara Diamond, Roads to Dominion, Right-wing Movements and Political Power, 1995. Guilford Press.

[31] William F. Buckley, “Goldwater, the John Birch Society, and Me,” Commentary Magazine, March 2008, https://www.commentarymagazine.com/articles/william-buckley-jr/goldwater-the-john-birch-society-and-me/.

[32] In the early 1990s, John F. Buckley called out well-known paleoconservative Pat Robertson for antisemitism in a scathing article in the National Review. He later turned the essay into a book, In Search of Anti-semitism, 1992. Ed Conroy Booksellers. See also: Murray Freidman, The Neoconservative Revolution: Jewish Intellectuals and the Shaping of Public Policy, 2005, Cambridge University Press.

[33] Chip Berlet, “ZOG Ate My Brain,” New Internationalist, October 2, 2004, https://newint.org/features/2004/10/01/conspiracism.

[34] Carolyn Gallaher, 2003, On the Fault Line: Race, Class, and the American Patriot Movement, Rowman and Littlefied.

[35] Jesse Walker, 277.

[36] Heidi Beirich, “Exploring Nativist Conspiracy Theories Including the ‘North American Union’ and the Plan de Aztlan,’” Intelligence Report, Summer 2007, https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/2007/explor…-‘north-american-union’-and-plan-de-aztlan.

[37] Patricia Sullivan, “Obituary: Militia-friendly Idaho Rep. Helen Chenoweth-Hage,” Washington Post, October 4, 2006, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/2006/10/04/militia-friendly-idaho-rep-helen-chenoweth-hage/9e77fc0f-5e1a-45c1-bc99-e573c45248ac/.

[38] Dave Gilsen, “Conspiracy Watch: The Amero,” Mother Jones, May/June 2007, https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2007/04/conspiracy-watch-amero/. See also: Chip Berlet, “Collectivists, Communists, Labor Bosses, and Treason: The Tea Parties as Right-Wing Populist Counter-Subversion Panic,” Critical Sociology 38, no. 4 (July 2012): 565–87.

[39] Emily Ekins, “Today’s Bailout Anniversary Reminds Us That the Tea Party Is More Than Anti-Obama,” Reason Magazine, October 3, 2020, https://reason.com/2014/10/03/the-birth-of-the-tea-party-movement-bega/.

[40] Chip Berlet, “Collectivists, Communists, Labor Bosses, and Treason: The Tea Parties as Right-Wing Populist Counter-Subversion Panic,” Critical Sociology 38, no. 4 (July 2012): 565–87.

[41] Mike Lofgren, “Anatomy of the Deep State,” Moyers on Democracy, February 21, 2014, https://billmoyers.com/2014/02/21/anatomy-of-the-deep-state/.

[42] See: Amarnath Amarasignam and Marc-Andre Argention, “The QAnon Conspiracy Theory: A Security Threat in the Making?” Combatting Terrorism Center, July 2020, https://ctc.usma.edu/the-qanon-conspiracy-theory-a-security-threat-in-t…; Mike Wendling, “QAnon: What is it and where did it come from?” BBC News, August 20, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/53498434; “What You Need to Know about QAnon,” Southern Poverty Law Center, October 27, 2020, https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/2020/10/27/what-you-need-know-about….

[43] For more information on QAnon see: Network Contagion Research Institute (NCRI), and Polarization and Extremism Research Innovation Lab (PERIL). “The QAnon Conspiracy: Destroying Families, Dividing Communities, Undermining Democracy.” Contagion and Ideology Report. Rutgers Miller Center for Community Protection and Resilience, December 15, 2020. https://networkcontagion.us/wp-content/uploads/NCRI-%E2%80%93-The-QAnon-Conspiracy-FINAL.pdf.

[44] Amarnath Amarasignam and Marc-Andre Argention, “The QAnon Conspiracy Theory: A Security Threat in the Making?” Combatting Terrorism Center, July 2020, https://ctc.usma.edu/the-qanon-conspiracy-theory-a-security-threat-in-t….

[45] To map the social networks that develop around public QAnon Facebook groups, we used CrowdTangle, a tool developed by Facebook to track and analyze social media data, and Facebook’s API. CrowdTangle is a Facebook-owned tool that tracks interactions on public content from Facebook pages and groups, verified profiles, Instagram accounts, and subreddits. (For more information see: https://help.crowdtangle.com/en/articles/4201940-about-us.) We used CrowdTangle to pull a list of public QAnon groups and all of their posts, which included links. Then, we used the Facebook API to identify other Facebook groups that shared the same links as the QAnon groups.

[46] Although links that are shared by multiple sources within a short time frame are not necessarily coordinated, coordinated link sharing behavior is associated with bots, inauthentic accounts, and sources that contain misinformation. See: Fabio Giglietto, Luca Rossi, Nocola Righetti, and Giada Marino, SMSociety ’20, July 22–24, 2020, Toronto, ON, Canada. Doi.org/10.1145/3400806.3400817.

[47] We began by searching for QAnon groups in CrowdTangle. We added groups that showed up in the search, and then added groups that were recommended from these groups. We then selected for the largest groups on this list, limiting the number to 23 groups to avoid a network that was too large to analyze in fine detail.

[48] We used the CooRnet package and Facebook API to do this.

[49] By accounts we reference the total number of members in all groups combined.

[50] To identify the core of the network, we removed groups that had connections with less than 10 percent of total groups in the network (specifically, any group that had less than 600 connections to other groups in the network).

[51] Density scores are presented as a percentage of total possible connections present in a network. In most “real” networks, one would expect the density to be less than 0.1 or 10 percent. For larger networks (like those on Facebook), one would expect the density to be even smaller, possibly 0.0001. This is because the more nodes in a network, the more possible connections overall.

[52] We defined groups as having a Patriot or militia ideology if they had the word “patriot” or “militia” in their name (Bigfoot Patriot Network, Digital-Militia Group) or referenced Libertarian or Tea Party ideology (Texas Tea Party Patriots PAC, The New Libertarian).

[53] E.g. Trump Patriots and Christian Patriots for Trump.

[54] These groups were: Chemtrails Global Skywatch, FIRST OFFICIAL CANDACE OWENS FAN CLUB, MA 4 Trump, The Rush Limbaugh Facebook Group, The “Real” Trump Army, FOX NEWS with Tucker Carlson, Drain The Swamp, Women SCOUTS for TRUMP (c), Donald Trump For President 2020!!!!!!, and ~*Q*~SENT ME[ME].

[55] These groups were: MA 4 Trump, The “Real” Trump Army, FIRST OFFICIAL CANDACE OWENS FAN CLUB, Donald Trump For President 2020!!!!!!, Drain The Swamp, The Rush Limbaugh Facebook Group, Chemtrails Global Skywatch, TRUMP TRAIN (Official), FOX NEWS with Tucker Carlson, Trump / Pence AGAIN in 2020 (c).

[56] We did not include non-political links in this top 50 category. As we note in an earlier footnote, far-right groups also like to occasionally share pet pictures or other personal posts.

[57] Kathryn Joyce, “The Long, Strange History of Bill Gates Population Control Conspiracy Theories,” HuffPost, May 18, 2020, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/bill-gates-coronavirus-vaccine-conspiracy_n_5eb9ab7ac5b69358ef8a9803?ncid=engmodushpmg00000004.

[58] Mekhennet, Souad, and Craig Timberg, “Nearly 25,000 Email Addresses and Passwords Allegedly from NIH, WHO, Gates Foundation and Others Are Dumped Online,” Washington Post, April 22, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2020/04/21/nearly-25000-email….

[59] Katherine Schaeffer, “Nearly three-in-ten Americans believe COVID-19 was made in a lab,” FactTank: News in the Numbers, Pew Research Center, April 8, 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/04/08/nearly-three-in-ten-am….

[60] We looked for groups who used the hashtag #stopthesteal over the course of a month, between October 23 and November 23 2020.

[61] These groups are: Fox New with Tucker Carlson, MA 4 Trump, Women SCOUTS for TRUMP (c), and TRUMP TRAIN (Official).

[62] Defined here as groups that were in the top 10 in terms of CLSB, direct connections to other groups in the network, or both.

[63] Eric Griffith, “1 in 10 Americans Don’t Believe the Moon Landing Really Happened,” July 18, 2019, PCMag, https://www.pcmag.com/news/1-in-10-americans-dont-believe-the-moon-land…

[64] “Sightings of Elvis Presley,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sightings_of_Elvis_Presley.

[65] Buchanan was defeated in 1992 by George H.W. Bush and in 1996 by Bob Dole.

[66] Marc Fisher, John Woodrow Cox, and Peter Hermann, “Pizzagate: From rumor, to hashtag, to gunfire in D.C.” Washington Post, December 6, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/pizzagate-from-rumor-to-hashtag-to-gunfire-in-dc/2016/12/06/4c7def50-bbd4-11e6-94ac-3d324840106c_story.html.

[67] Ari Sen and Brandy Zadrozny, “QAnon Groups Have Millions of Members on Facebook, Documents Show,” NBC News, August 10, 2020, https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/qanon-groups-have-millions-membe….

[68] Tommy Beer, “Facebook Has Failed To Expunge ‘Boogaloo’ Extremists, Report Claims,” Forbes, August 13, 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/tommybeer/2020/08/13/facebook-has-failed-t….