One of the lasting legacies of 9/11 is the growth and mainstreaming of conspiracy theories, across the U.S. and the world. Within hours of the attacks, theories cropped up online to identify culprits, explain their motives, and uncover their purported connections to the U.S. government. And they kept surfacing for years afterwards. Many of these conspiracy theories—that the U.S. military shot down United Flight 93 or that the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad planned the attacks—found an unprecedented level of popular support, repeated by politicians,[1] theologians,[2] and movie stars.[3] Some theories—particularly that a controlled explosion brought down the Twin Towers—were so durable they still have currency today, 20 years after the attacks.

The proliferation and normalization of 9/11 conspiracy theories can be explained broadly by three factors. The official narrative of the 9/11 attacks raised as many questions as it answered, creating an information vacuum. Provocateurs were then happy to fill that void. And these actors married traditional forums of dissemination, such as talk radio, with newer forms, like internet chat rooms and blogs. Their combined reach brought heretofore untapped audiences into the conspiratorial fold.

The official narrative of the 9/11 attacks raised as many questions as it answered, creating an information vacuum.

Despite the unprecedented nature of the 9/11 attacks, many of the conspiracy theories about them followed a familiar Generically used to describe factions of right-wing politics that are outside of and often critical of traditional conservatism. Learn more playbook: find foreign masterminds—often Jews—and allege that they worked with traitors inside the U.S. political or economic establishment to undermine America’s power. In the U.S. conspiratorial canon, antisemitic and anti-government sentiments have long gone hand in hand.

Conspiracy Theories and What They Tell Us

If a conspiracy is a secret plot between two or more people, a conspiracy theory is an alleged plot for which there is limited or no evidence. Conspiracy theories rarely provide insight into the events they are supposed to explain, but they do say a lot about the people who believe them. A conspiracy theory is often a fabulist version of believers’ experiences, biases, fears, and even hopes.[4]

If we look at 9/11 through this lens, Americans who believed 9/11 conspiracy theories were deeply suspicious of their government. They didn’t just think the government was negligent, though. They were convinced it was malevolent. To explain the presumed malice, however, conspiracists didn’t look inward. They pointed to foreign “puppet masters,” whom they accused of duping or manipulating government officials to work against U.S. interests.

9/11 conspiracy theories are popular across the political spectrum, and many were crafted by people who didn’t have explicitly left- or right-wing politics in mind. But the Far Right embraced them more vigorously, and more effectively, than their counterparts on the Left. The production of Loose Change, a self-produced movie about 9/11, is a good example. The film was created by amateurs without a clear political perspective, but by the film’s third updated edition, right-wing conspiracist and talk show host Alex Jones had gotten involved.[5] At the time, Jones wasn’t well known outside of Austin, Texas, but he’d been parroting and amplifying anti-government views on his radio show since the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995. He used his involvement in the film to expand his following dramatically.

Many leftist conspiracy theorists also morphed into right-wing theorists over time. As journalist David Neiwert, author of Red Pill, Blue Pill: How to Counteract the Conspiracy Theories That Are Killing Us, notes, conspiracy theories disorient people by eroding their trust in institutions and information sources. In their attempts to salve their anxiety, adherents of conspiracy theories often seek out authoritarian people and solutions, with the result that leftist theories are often “absorbed into the larger alternative universe of conspiracy theories, and become more and more right-wing.”[6]

Official Narratives

Watching footage of the Twin Towers collapsing on a bright, late-summer morning was a shared, sometimes formative trauma among people old enough to remember the attacks. The footage ran on loop on network and cable television for days. For many people—myself included—it was hard, if not impossible, to look away.

These theories were able to take hold in large part because traditional actors responsible for communicating the truth about 9/11 were not themselves truthful about the political choices they made in response to the attacks.

Within this inescapable atmosphere of shock and loss, the Bush administration almost immediately started building a narrative to explain the attacks. On the evening of September 11, 2001, Bush addressed the nation and described the attacks as evil and the attackers as terrorists.[7] On the night of the attack, the CIA told the president that the agency was still assessing responsibility, but “the early signs all pointed to al Qaeda.”[8]

Although the administration publicly identified Al Qaeda as the guilty party shortly thereafter, the war it launched in response was targeted more broadly. As the 9/11 Commission noted in its 2004 report, within hours of the attacks, Bush’s war cabinet encouraged him to go after not just Al Qaeda, but any countries that might have helped them. Then-Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld reportedly identified five enemy countries. The first was Afghanistan, where Al Qaeda was then operating. The other four—Iraq, Iran, Libya, and Sudan—had few if any current connection to group.[9]

The administration invaded Afghanistan immediately, but within two years it would launch a new war in Iraq, on the pretext that Iraqi President Saddam Hussein had worked with Al Qaeda’s Osama Bin Laden and that Hussein was building a nuclear arsenal. Both assertions proved to be false.

The administration’s changing narrative had the effect of sowing confusion and doubt. And the title they gave their new fights, the “War on Terror,” captured that uncertainty. It was a name that failed to identify an enemy, a place, or even an ideology. It was, as one geographer put it, an “Everywhere War.”[10]

9/11 and the Right

Politically, these inconsistencies provided fodder for Bush’s Democratic opponents. They also proved useful to groups on Bush’s Right flank. Indeed, 9/11 provided the Far Right a chance at a clean slate after a difficult decade. Successful lawsuits in the 1990s against the White Aryan Resistance and the Aryan Nations, for example, had hobbled two of the most powerful White nationalist/White supremacist groups in the U.S. The anti-government Patriot movement was also on the backfoot after the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, and its attempts to regain relevance around Y2K had fizzled once predicted disruptions failed to materialize.

However, the two wings of the Far Right responded differently to the opportunity. For their part, the Patriot movement had a muted reaction. Martin Durham, a scholar of the Far Right, argues that 9/11 had a demobilizing effect on the movement.[11] Some militia leaders questioned whether the attacks were designed to pave the way for martial law, but most did not feel comfortable cheering a foreign attack on U.S. soil. And once U.S. forces were sent into Afghanistan, most militias were loath to go on the attack against active-duty soldiers.[12] Many militia leaders in the 1990s had served in the Vietnam War and knew what it felt like to go into a war without the support of their fellow citizens. As such, even though Patriot groups bristled at provisions for heightened surveillance in the administration’s Patriot Act, they were reticent to mobilize against it in the way that they had done during the farm crisis in the 1980s and after Waco and Ruby Ridge in the ‘90s. But even if they had chosen to mobilize, they would have faced stiff headwinds. During the early years of the war, displays of patriotism were increasingly used as cudgels against war opponents.

White nationalists and neonazis took a different approach. They cheered the attackers for striking at the heart of the so called Zionist Occupied Government (ZOG), a pejorative label they use to suggest the U.S. government is controlled by Jews. Given their dim view of the U.S. government, both groups were quick to reject the government’s official narrative as a falsehood. Some believed Al Qaeda wasn’t involved; others acknowledged its involvement, but claimed the group was only supporting the attack’s Jewish or Israeli masterminds, who were being protected by lackeys in the U.S. government (a confounding claim given the centrality of A form of oppression targeting Jews and those perceived to be Jewish, including bigoted speech, violent acts, and discriminatory policy. Learn more to Al Qaeda ideology).[13]

According to the Anti-Defamation League, antisemitic conspiracy theories about 9/11 generally followed two tropes[14]—they were designed to either prove or corroborate allegations of Jewish involvement. The conspiracy theory that suggests the Israeli Intelligence Agency Mossad planned the attack is an example of the first. So is the theory that Jewish owners of the World Trade Center imploded the buildings so they could collect insurance money. The allegation that 4,000 Israeli workers at the Twin Towers stayed home on the day of the attacks is an example of the second. Those workers might not have known about the attack, the conspiracy goes, but their decision to skip work proves Israeli involvement.[15]

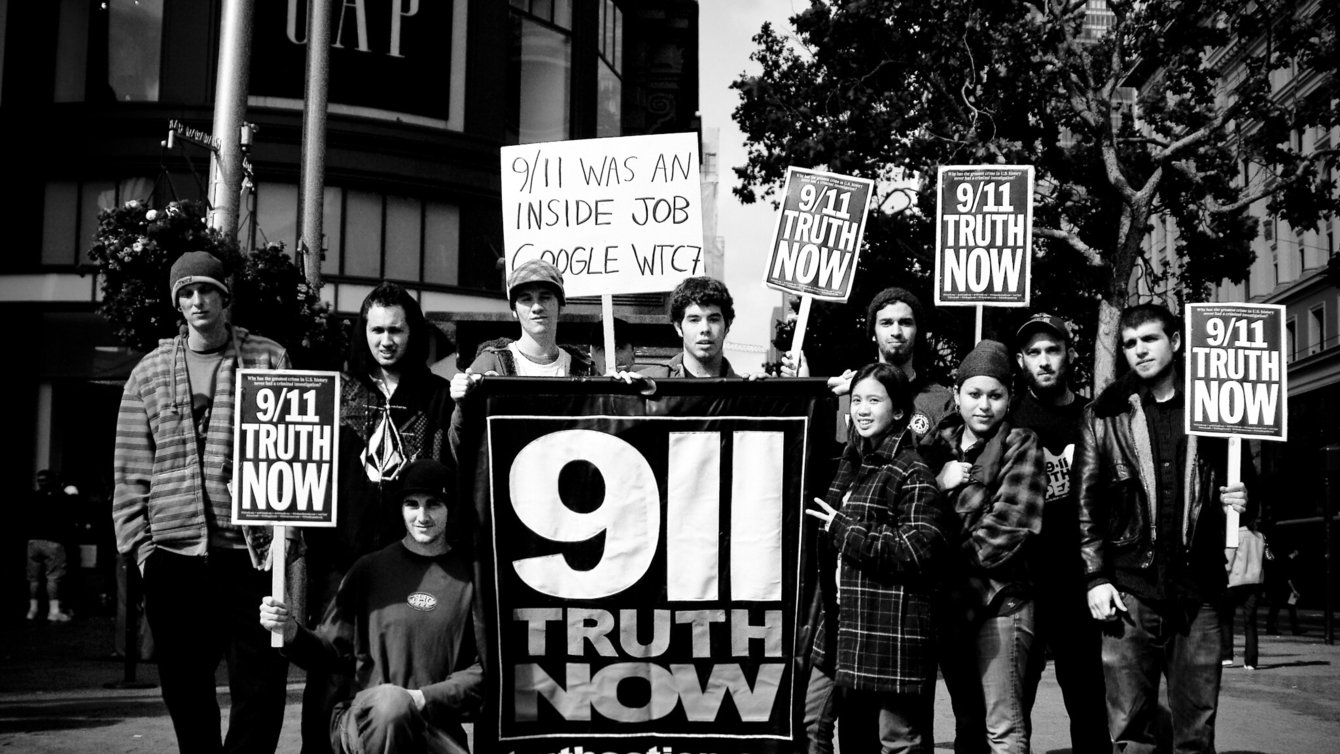

While far-right groups were early purveyors of 9/11 conspiracy theories, conspiracy mongering was democratized after 9/11. Conspiracy making has always been an iterative process, wherein like-minded conspirators exchange ideas as they build a common understanding of events. But mass media—talk radio, public access television shows, and the internet, in particular—allowed more people to get into the mix. Talk show hosts like Alex Jones, for example, introduced and amplified multiple conspiracies theories about 9/11. Listeners could then continue those conversations on the internet, in chat rooms, on blogs, and listservs. And because these venues reached people across the county, conspiracy theories could take on a life of their own. The so-called 9/11 Truther Movement is a case in point. Although a loose coalition of organizations created the movement, its theories were often modified, updated, and then amplified by others. Today, multiple groups, some with competing views, claim the movement mantle.

The spread of 9/11 conspiracy theories far and wide also meant it was easy to capitalize on the doubt. Over the last 20 years, hundreds of books, movies, and articles have been published that call into question the official course of events.

The Fallout

In many respects, 9/11 was the first attack of its kind in the U.S.: the first to successfully strike the Pentagon, to use commercial jets as weapons, or to hit three large targets at once. It was also unique politically, as the first attack in which many of the perpetrators were citizens of a close U.S. ally-state, Saudi Arabia. Casualties also made 9/11 stand out, with a death toll that remains the largest of any terrorist attack inside U.S. borders.

Despite all of these firsts, the country’s far-right conspiratorial lexicon remained firmly rooted in tradition. Government was the enemy because it had supposedly been co-opted, if not fully “occupied,” by foreign Jewish infiltrators. Indeed, most far-right theories ignored or downplayed seemingly obvious targets of suspicion like the Saudi government.

The legacy of 9/11 A mode of political explanation that assumes a vast insidious plot against the common good. Learn more continues today. The same narrative that underpins many 9/11 conspiracies—Jewish masterminds infiltrating the U.S. government—also inform contemporary QAnon conspiracy theories. The main difference is one of scale. When 9/11 happened, Facebook and Twitter didn’t yet exist. Today, both social media giants, as well as dozens of smaller platforms, have allowed conspiracy theories to spread even more quickly, and over even larger territories, than talk radio or earlier internet forums ever achieved.[16]

The effects of 9/11 conspiracism extend beyond the events of that day and helped erode a common sense of truth in U.S. society. But it’s important to recognize that these theories were able to take hold in large part because traditional actors responsible for communicating the truth about 9/11—most notably government officials—were not themselves truthful about the political choices they made in response to the attacks. The Bush administration set the stage for lies, half-truths, and misdirection, and successive administrations followed suit.[17] In effect, they’ve made it easy for the truth to be questioned, and for “alternative truths” to advance. The result is that disinformation and misinformation now have built-in audiences on social media and beyond.

Stopping the spread of disinformation and misinformation by social media platforms is a vital first step. But for truth to exist—for there to be things that all Americans take as givens—we need arbiters of truth. Given the widespread suspicion of the federal government, the best place to build up such arbiters is at the local level. Unfortunately, in many places across the country, such traditional local arbiters—churches,[18] municipal leaders,[19] school boards,[20] state level political parties[21]—are now under the sway of toxic conspiracy theories themselves. Going forward, the ground game against disinformation must be local, and multi-sited—a new sort of “everywhere” fight against the conspiracism that’s torn us apart.

- Endnotes

[1] Ben Jacobs, “9/11 Truthers Can Be Politicians, Too,” The Daily Beast, July 12, 2017, https://www.thedailybeast.com/911-truthers-can-be-politicians-too.

[2] David Heim, “Whodunit? A 9/11 conspiracy theory,” The Christian Century, September 5, 2006, https://www.christiancentury.org/article/2006-09/whodunit.

[3] Ryan Parker, “Charlie Sheen on His Surprising New ‘9/11’ Movie and Those Truther Comments,” The Hollywood Reporter, September 8, 2017, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/general-news/charlie-sheen-9-11-movie-truther-comments-1036494/

[4] Jesse Walker, The United States of Paranoia: A Conspiracy Theory (Harper Perenniel, reprint, 2014), p. 15.

[5] John McDermott, “A Comprehensive History of ‘Loose Change’—and the Seeds It Planted in Our Politics,” Esquire, September 10, 2020, https://www.esquire.com/news-politics/a33971104/loose-change-9-11-consp….

[6] Deyanira Marte, “Red Pill, Blue Pill: Q&A with Author David Neiwert,” Political Research Associatess, June 23, 2021, https://politicalresearch.org/2021/06/23/red-pill-blue-pill.

[7] George W. Bush, “Address to the Nation on the September 11th Attacks,” 2001, George W. Bush, White House Archives. https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/infocus/bushrecord/documents/Selected_Speeches_George_W_Bush.pdf.

[8] National Commission On Terrorist Attacks Upon The United States, The 9/11 Commission Report: Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, 2004, Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://lccn.loc.gov/2004356401, p.326.

[9] Ibid, p. 330.

[10] Derek Gregory, “The Everywhere War,” The Geographical Journal (2011) 177(3): 238–250.

[11] Martin Durham, “The American Far Right and 9/11,” Terrorism and Political Violence (2003) 15(2): 96-111

[12] Carolyn Gallaher and Jaclyn Fox, “Could Anti-Government Militias Become Pro-State Paramilitaries?” The Public Eye, Fall 2020, https://www.politicalresearch.org/2020/10/27/could-anti-government-militias-become-pro-state-paramilitaries.

[13] Anti-Semitism: A Pillar of Islamic A generic category for anyone who holds beliefs outside of those approved by mainstream or broadly centrist preferences. Learn more Ideology, Anti-Defamation League, 2015, https://www.adl.org/sites/default/files/documents/assets/pdf/combating-hate/Anti-Semitism-A-Pillar-of-Islamic-Extremist-Ideology.pdf.

[15] There is no evidence there were 4,000 Israeli citizens working in the World Trade Towers.

[16] Jaclyn Fox and Carolyn Gallaher, “Conspiracy for the Masses,” The Public Eye, Winter 2021, https://www.politicalresearch.org/2021/01/29/conspiracy-masses.

[17] Craig Whitlock, “At War with the Truth,” Washington Post, December 9, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/investigations/afghanistan….

[18] Mike Allen, “Qanon Affects Churches,” Axios, May 31 2021, https://www.axios.com/qanon-churches-popular-religion-conspiracy-theory-c5bcce08-8f6e-4501-8cb2-9e38a2346c2f.html.

[19] Vera Bergengruen, “QAnon Candidates Are Winning Local Elections. Can They Be Stopped?” Time Magazine, April 16, 2021, https://time.com/5955248/qanon-local-elections/.

[20] National Education Association, “Is QAnon Radicalizing Your School Board?” 2021, https://www.nea.org/advocating-for-change/new-from-nea/qanon-radicalizing-your-school-board.

[21] Blake Montgomery, “Minnesota County GOP Event Featured Conspiracy Theorist Who Said George Floyd’s Murder Was Planned,” The Daily Beast, April 24, 2021, https://www.thedailybeast.com/minnesota-gop-event-featured-conspiracy-theorist-trevor-loudon-who-said-george-floyds-murder-was-planned.