Political violence has been on the rise in the United States amidst a particularly volatile political climate. In a survey[1] conducted in 2021 by the National League of Cities, more than 80 percent of local officials across the U.S. said they had been threatened or harassed. But research also shows that a large majority of Americans disapprove of the use of political violence. What is political violence, and what damage does it do to democracy? How can communities facing the threat of political violence respond strategically and meaningfully? Harnessing Our Power to End Political Violence (HOPE-PV), a new training project from the 22nd Century Initiative and the Horizons Project, helps us answer these questions and more.

PRA spoke with Hardy Merriman, President of the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict and author of the HOPE-PV Project’s Harnessing Our Power to End (HOPE) Political Violence[2] guide, and Scot Nakagawa, Executive Director of the 22nd Century Initiative, about political violence, its impact on our democracy, and how we can make it backfire. Their September 2024 interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Harnessing Our Power to End Political Violence Guide (Credit: Hope-PV)

PRA: Can you tell us about this project and why you wrote this guide?

Scot Nakagawa: The HOPE-PV Project originates with the Horizons Project and the 22nd Century Initiative. We were responding to the incredible rise in political threats. That, along with actual incidents of political violence, has created an atmosphere of fear that greatly impacts people’s political participation, which is essential to a healthy democracy. We felt this needed to be confronted. We recognized that there are many efforts toward digital and physical security, greater police accountability, and supporting survivors of political threats and violence. But what seemed to be missing is a political response—an attempt to make these incidents backfire on their perpetrators, to raise the cost to them for behaving in that way. We thought we should fill the gap.

Hardy Merriman: I was thrilled to be asked [to write the guide] because I had been deeply concerned about political violence since seeing it start to rise around 2016. After the 2020 election, there was a growing recognition that U.S. elections can be subverted. While there are many threats to U.S. democracy, political violence was the one that kept me up at night. It’s an epidemic that affects our public life in countless ways. For example, we don’t know how many people have decided not to run for public office because they were afraid of political violence. Those who step down may not be forthcoming about how it affected their decision. And people in office—how are their decisions affected by this? How are election workers, activists, and historically marginalized communities affected? We know they are.

Top-down ways of addressing political violence have been overemphasized. Government, social media companies, and advocacy groups all need to play a role, but without community engagement, those approaches are inadequate. We need bottom-up.

Why is political violence on the rise? Because it gets results. Those who incite threats benefit in trying to achieve a political goal. The way to reduce the demand for that is to make it backfire by making it more costly for them—to make sure that their use of violence has the opposite effect.

“Political violence is very damaging to U.S. democracy. With it, a small group intends to gain power outside of the democratic process.”

PRA: What is political violence? What forms does it take here in the U.S., and what impact does it have on democracy?

Hardy Merriman: In simple terms, political violence is the use of violence to try to achieve a political goal or advance a political message.

What do we mean when we say violence? Our definition includes inflicting physical harm on people and acts that make people fear that you will inflict physical harm upon them, such as making and sending threats, using weapons for intimidation, and doxxing people, which is putting their information online to enable others to harass and threaten them. When those acts are done to advance a political goal or political message, that can qualify as political violence. We look at the perpetrator’s intention when deciding to use the term “political.” All acts of violence have political implications—whether interpersonal or structural—but when that violence is done with [a] particular political motivation, we call it political violence.

And its effects are huge. Political violence is very damaging to U.S. democracy. With it, a small group intends to gain power outside of the democratic process. Through violence, they instill fear to limit our exercise of constitutionally-guaranteed rights, like that of free speech. They try to reduce voter turnout during elections, and then dispute the results to circumvent the process. They can also use it to try to drive people from public service, threaten judges and juries, and get businesses to stop taking certain positions.

And this country has a history of using political violence to keep entire populations in fear: It’s part of the glue that held together the Jim Crow South. It’s been targeted at groups such as An umbrella acronym standing for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning. Learn more people. It’s been targeted at workers and laborers who seek fair wages and safe working conditions. And it’s used against those who show solidarity with those groups. Unless we stop it, I fear it will continue to get worse.

Scot Nakagawa: The impact of political violence and threats is profound. Organizations, for example, are rolling back canvasses and losing volunteers because people aren’t willing to expose themselves and their families to the possibility of threats and violence. [This is] a critical issue that we need to deal with by reminding people that the vast majority of us oppose most violence, and certainly political violence of this kind. We must get people to feel they belong to the majority and give them the opportunity to take actions they feel are real and palpable.

“Perpetrators threaten people to silence them and offer bribes as rewards for staying quiet. We must resist this and be prepared to turn such efforts into backfire opportunities.”

PRA: Can you describe the guide’s backfire strategy and how activists might use it to effectively counter political violence?

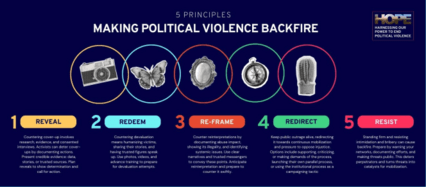

Hardy Merriman: The Backfire Model is a five-step process for getting political violence to backfire against perpetrators [of that violence]. It’s drawn from examples all over the world. A group of scholars[3] studied repressive acts of violence to understand why they backfire at some times and not others. They discovered that perpetrators use a five-step playbook to try to inhibit outrage against their abuse, which means there are five steps to make their actions backfire: reveal, redeem, reframe, redirect, and resist.

5 Principles of the Backfire Mdoel (Credit: Hope-PV)

First, since perpetrators will deny the abuse is happening at all, often by claiming it’s not real, activists and community members must reveal it—and in a way that does not cause greater fear, which is the work of political violence. You want to reveal it on your terms, in your language, with your people and allies to show you have solidarity.

Second, perpetrators try to devalue the victim by leveraging Individual beliefs that favor one group over others, or disfavor a particular group, and/or laws, policies and traditions that inscribe such beliefs in institutions. Learn more and bias, spreading false information, taking something wildly out of context, or trying to provoke a reaction. We want to redeem the person by emphasizing their story and values—not to present them as perfect, but to show they are part of the community and are worthy of our care and attention.

Third, perpetrators try to reinterpret events to minimize the impact [of violence] and their role. To counter this, activists can reframe the narrative. We need to say: this is something systemic and the damage is real. We can’t let those who incite violence off the hook.

Fourth, when the first three tactics fail, perpetrators may accept a formal investigation process—judicial or otherwise—but they’ll try to control the process by dragging it out while limiting information and access. Activists can demand an open and accessible process. But we can also redirect from relying on institutional processes to deliver justice, and instead use them as opportunities for mobilizing and public education.

Fifth, perpetrators threaten people to silence them and offer bribes as rewards for staying quiet. We must resist this and be prepared to turn such efforts into backfire opportunities.

“A huge amount of progress is predicated upon being able to reframe issues in the context of violence.”

PRA: I love that using backfire strategies puts us on the offensive. Another strength of the training that we’ve developed based on the guide is its use of case studies. How have communities used backfire in action and what have you seen happen on the ground?

Hardy Merriman: We can learn much from the brilliance of movements that came before us. You will not find a better example of engaging a backfire strategy than the Civil Rights Movement. They deeply understood the principles. They planned. They were prepared. The Nashville lunch counter sit-ins, the Birmingham campaign, and other actions were remarkably effective in using backfire principles. The same is true of some of the United Farm Workers’ tactics while organizing in grape vineyards in the 1960s.

There are also recent examples. In Whitefish, Montana, when White supremacist and neo-Nazi group activity was damaging the town’s reputation, some residents created Love Lives Here. The town rallied when armed groups put out a call to march in 2017 on Martin Luther King Day. Businesses put “Love Lives Here” stickers up and held public actions designed to include people and display their joy and strength. Numerous groups—indigenous rights, labor, LGBTQ, Republican, and Democrat—came together to oppose the march. The town resisted, created a counternarrative, and ended up stronger. As a result, the marchers didn’t even show up! That’s a clear example of backfire.

Scot Nakagawa: In Portland, Oregon, in 1992, an evangelical group proposed a horrific ballot measure[4] that dehumanized LGBTQ people by demanding that homosexuality be named “abnormal, wrong, unnatural and perverse” in the state’s Constitution. In the context of that campaign, there was extraordinary violence. People formed the Homophobic Violence Documentation Project to document incidents as they happened and interview people who were victimized to humanize them. Going beyond the numbers helped people see how ordinary people—LGBTQ people and straight allies—were being attacked for putting up lawn signs and bumper stickers, making public statements, and community canvassing. And with media coverage of these stories, people started to lead kitchen-table discussions about the measure’s implications. It had a profound impact.

I once worked at the Highlander Center, one of the Civil Rights Movement’s cradles. During one of my jobs in the library, I read the archives and journals of people trained by the Center. It was an extraordinary effort to stop political violence—and to use [evidence of the perpetrator’s violence] to advance the civil rights cause. Marchers knew they would face resistance and potential violence, but when confronted by hostile law enforcement and citizens, they didn’t back down. This forced a different kind of conversation to emerge among people witnessing this violence about what it means to live in a democratic society as the dominant majority: Do I want to participate in that majority if it results in this kind of violence?

A huge amount of progress is predicated upon being able to reframe issues in the context of violence. While it feels hard to think of this as an opportunity, I strongly believe it is one. It’s an opportunity to drive a wedge with a huge majority of people on the side of nonviolence. Nonviolence is a bedrock principle of a healthy democracy.

“The struggle to uphold democracy is ours, as a people. It is not just the government’s job to counter political violence. It falls to all of us.”

PRA: What should people do to learn more about backfire?

Scot Nakagawa: People should go to the website, endpoliticalviolence.org, to get the guide and other resources. They can also reach out to us to bring trainers to their community and get trained as trainers. We want practitioners to be able to engage communities and provide people with tools to act nonviolently in response to political violence, so we can participate in and save our democracy.

Hardy Merriman: The struggle to uphold democracy is ours, as a people. It is not just the government’s job to counter political violence. It falls to all of us. As Scot said, we must see that as an opportunity. Research tells us that a bipartisan majority of Americans [believes] that political violence is unacceptable. There are many ways to engage with that. Not everyone has to be a frontline activist. We need researchers, communicators, lawyers. There’s a place for everyone and all skill sets. Together, we can turn the tide.

Scot Nakagawa: My last word is: don’t obey in advance. That’s exactly what political threats attempt to do—get us to obey authoritarian power. The authoritarian movement represents a minority of people who are attempting to take power through the democratic process by dividing us. Engaging in the effort to confront political violence is critical if we want to protect and expand democracy. I encourage people to connect with us and make sure that your activist toolkit includes as many tools as possible for addressing violence.

- Endnotes

[1] National League of Cities, “New Report: Harassment, Threats and Violence Directed at Local Elected Officials Rising at an Alarming Rate,” November 10, 2021, https://www.nlc.org/post/2021/11/10/new-report-harassment-threats-and-v….

[2] Hardy Merriman, Harnessing Our Power to End (HOPE) Political Violence (22nd Century Initiative and the Horizons Project, 2024), https://www.endpoliticalviolence.org/guide.

[3] Brian Martin, Backfire Manual: Tactics Against Injustice (Sparsnäs: Irene Publishing, 2012), https://www.bmartin.cc/pubs/12bfm/index.html, on the backfire approach; also refer to Martin, “Backfire Materials,” https://www.bmartin.cc/pubs/backfire.html, for a bibliography on the subject by one of the most well-known in this group of scholars.

[4] “2: Ballot Measure 9,” No On 9 Remembered, accessed October 29, 2024, https://noon9remembered.org/stories/ballot-measure-9/.