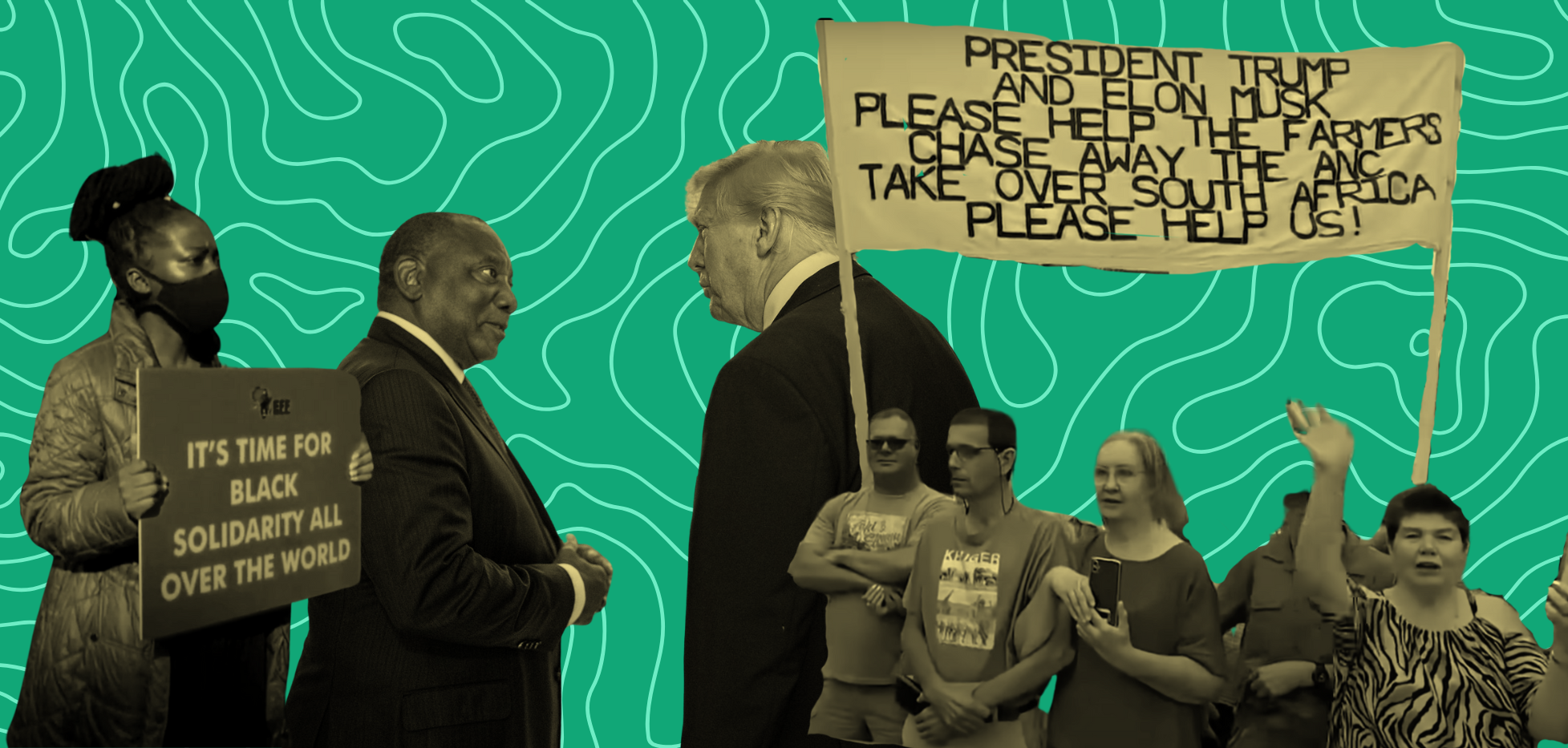

At an Oval Office meeting in May 2025, Donald Trump confronted South African President Cyril Ramaphosa with a picture of people carrying body bags. Invoking a central trope of the racist Right, he declared, “These are all white farmers that are being buried.”[1] Ramaphosa hoped the meeting would strengthen relations between their countries after cuts in aid and looming tariffs, but Trump had other ideas.[2]

Trump held up the image as evidence of the mass killings of White Afrikaners—the descendants of European (mostly Dutch) settlers in South Africa. As he did, President Ramaphosa, prepared for a potentially tense encounter amid trade discussions, looked on placidly while challenging the accuracy of Trump’s depiction of his country in a staged onslaught that recalled Trump’s February 2025 bullying of Ukraine’s President Zelenskyy.[3]

In fact, Trump’s image was not of “White farmers,” nor were they from South Africa. The original image was a screengrab from Reuters footage of humanitarian workers attending to the remains of people killed during armed conflict in Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo.

Though it was false, the story of White farmers killed because of racial prejudice perpetuates a narrative of a global persecution against White people that furthers the Trump administration’s anti-immigrant objectives. The Trump Administration offered in February to resettle White South Africans. A press release, written by Tammy Cruce, described Afrikaner refugees as victims of “unjust racial discrimination.”[4] And in May, days before his meeting with Ramaphosa, he referred to a “genocide” of White farmers being “brutally killed” when defending his administration’s acceptance of 59 Afrikaners as refugees from South Africa.[5] As historian James Alexander Dun points out, the acceptance of White Afrikaners is a “glaring exception to the general halt [the administration] has put on the entry of people fleeing persecution from around the world.”[6] Indeed, residents from the Democratic Republic of Congo, the actual scene of the violent images, were almost universally excluded from the possibility of refugee resettlement in the U.S. following the suspension of the U.S. refugee program shortly after Trump took office.[7]

Many critics of Trumpism will roll their eyes at his Oval Office antics with Ramaphosa as mere shenanigans, pointing to his duplicitous use of the images and the absurdity of the claims of anti-White persecution. Yet such a dismissal ignores the profound danger of the narrative animating these efforts. In this narrative, the world can only be understood through a racial lens, where there exist only racial winners and losers and racism is a zero-sum game. This view prioritizes protecting White racial power, particularly demographic power, above all other issues.

Stories about Afrikaner persecution must be understood within a broader set of White nationalist beliefs that contend a “race war” is under way against White people. The ideas of “White genocide,” “the great replacement,” and Afrikaner persecution each fit within this narrative of an unfolding global race war that threatens White people existentially. This central myth can motivate White people to adopt antidemocratic ideas and enact or support violence.

Along with foregrounding a key White nationalist myth, the story of global White persecution incites racial insecurities among a broader group of White conservatives in the U.S. by speaking to a widely shared understanding of race as a biological hierarchy while stoking demographic anxieties. Mining this particular view of race is necessary for understanding the growing reach of conservative and far-right social movements today. This is particularly important for understanding the anti-immigrant movement, which deploys such beliefs to present the country’s changing demographics as a threat, fueling support for anti-immigrant policies. This view of race is crucial to understand the contemporary anti-immigrant movement and its ties to White nationalist ideology.

White Nationalist Ideas on the Rise

When Trump spoke about anti-White persecution in South Africa from the Oval Office, he brought a central White nationalist claim to a global audience. While much of the media coverage has focused on the narrative’s falsity and what is and isn’t happening in South Africa, less discussed is what this story says to White audiences in the U.S. For White nationalists, talking about violence against Afrikaners is evidence that a race war is already under way against White people globally—and online discourse has been key to spreading their ideas to larger audiences. Ideas that were once marginal have now found their way into policy.

White nationalists were early Internet adopters, and as a result, their movement has expanded significantly in scope and reach in the two decades since I started studying and monitoring the online movement. At first, they formed chatrooms through dial-up networks to grow their numbers and influence.[8] Over the years, they built elaborate digital communities,[9] spread disinformation,[10] and created their own platforms. But the movement’s ideology remained much the same—a uniquely American brand of anti-Jewish prejudice, anti-Black racism, and anti-immigrant prejudice—and hovered on the margins of public discourse.[11]

During the 2010s, the movement began to reach broad audiences, as people all over the world rushed online to participate in social media, developing online presences and identities and spending increasing amounts of time consuming digital content. White nationalists were ready for this moment, as algorithms brought this small movement a virtual megaphone to communicate with audiences previously unimaginable.[12] In the past decade the reach of White nationalism has multiplied.

The Zero-Sum Game of Racism

The widespread circulation of White nationalist doctrine today is particularly dangerous, as these ideas interact with understandings of race and racism that extend far beyond the movement. A nationally representative survey of Black and White Americans found that a majority of White people believe that as people of color experience less discrimination Whites experience more.[13] Fear of changing racial demographics is also linked to increasingly anti-democratic views among White Americans, including support for violence as a means of defending the racial status quo[14] and other antidemocratic ideals. This is particularly true for those aligned with Christian nationalism.[15] Christian nationalism in particular supports a hierarchical view of society, one where Christians and men should be leaders, and in this way challenges the pluralistic values upon which democracies depend.[16] These widespread ideas about Whiteness as a newly persecuted racial group provide a fertile recruiting ground for the expanding White nationalist movement and narratives of racial resentment.

Within this hierarchical thinking, there is always one group on the top doling out suffering and receiving privileges. Importantly, this view of identity is rooted in Whiteness. In The Great Wells of Democracy, Manning Marable contrasts White and Black views of freedom. He writes, “‘Freedom’ to white Americans principally has meant the absence of legal restrictions on individual activity and enterprise. By contrast, black Americans have always perceived ‘freedom’ in collective terms, as something achievable by group action and capacity-building. ‘Equality’ to African Americans has meant the elimination of all social deficits between blacks and whites—that is, the eradication of cultural and social stereotypes and patterns of social isolation and group exclusion generated by white structural racism over several centuries.”[17]

The visibility of the Black Lives Matter movement and other calls for racial justice provide an opportunity for White people to grapple with the reality of ongoing racial inequality and their responsibility to challenge racism. Changing racial demographics due to differential birth rates and non-White immigration has also been changing the hegemony of Whiteness. However, the White nationalist movement and far-right media provide a competing understanding of contemporary race relations, one that reframes White people not as beneficiaries of centuries of violent supremacy, but instead as innocent victims.

White Genocide and the Belief in White Victimhood

While advocating White supremacy, a central objective of the White nationalist movement is to convince other White people that they are actually victims—or potential victims—of what they see as a race war, in which people of color seek to commit genocide against White people. This belief is articulated in the concept of “White genocide,” which gained public attention during Trump’s first presidential campaign when the then-candidate retweeted a post from the Twitter handle “WhiteGenocideTM.”[18] Since then, the idea has dominated White nationalist conversations.[19] One 2016 study found that it had become the most popular term among White nationalists on Twitter (now X).[20]

In such discussions, the idea of White genocide is not hyperbole or fantasy but an imminent, existential threat. Take for instance the following post to a White nationalist chat room: “‘Don’t make me extinct!’ Why do I have to justify my existence? When someone says they don’t care if whites disappear, point at a white child and say, ‘So you don’t care if she becomes extinct?’ There is no comeback to that.”[21]

The contemporary White nationalist focus on White genocide is a new manifestation of historical efforts to frame White people as racial victims while arguing for the need to grow and cultivate a White population. These efforts at different times have come from social movements and political actors, at times focusing on excluding those dubbed non-White from the U.S. and at others of imploring Whites to reproduce at higher numbers. President Teddy Roosevelt famously warned against the dangers of “race suicide” in a 1905 speech, “On American Motherhood.”[22] He warned that declining birthrates among Americans could lead to what he called “race suicide” and framed the duties of motherhood largely as a responsibility to reproduce the race, seeing in the work of motherhood “the foundation of all national happiness and greatness.” While Roosevelt didn’t explicitly reference race in his speech, the concept of “race suicide” was coined by sociologist and eugenicist Edward A. Ross a few years earlier.[23] For Ross, increasing immigration specifically from Asia was threatening the racial make-up of the United States, requiring “collective action.”[24] Fear of racial suicide helped to nurture the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan in the early 20th century, fueling the growth of the Klan into an influential national movement.[25] Today, themes of “race suicide” are being articulated anew in the pronatalist movement, which as Gaby Del Valle shows is uniting a new coalition of tech biohackers and conservative Christians.[26]

The idea of “race suicide” reveals a view of Whiteness as an inherently fragile social phenomenon, which can be traced to the fact that Whiteness—at least in its settler state varieties—is based on the delicate notion of ethnic purity. In the U.S., Whiteness emerged as a legal category, what legal scholar Cheryl Harris[27] describes as a form of property, which secures a variety of both public and private benefits. The perimeters of Whiteness have changed significantly over time,[28] representing the fluidity of this concept. This makes Whiteness seem unstable. While the online White nationalist movement has allowed the spread of these radical ideas into far-reaching venues, stories of White victimhood also rest on this understanding that Whiteness is inherently fragile and in need of protection.

Playing on Fears of Replacement

Framing White people as racial victims nurtures a grave misunderstanding that most White Americans already have about contemporary race relations to stoke fear of an existential threat. In so doing, the White nationalist narrative foments the possibility of racist violence against people of color. It also encourages support for anti-immigrant policies presented as protecting White people from non-White immigrants. In this view, non-White immigration is not a product of economic, labor, environmental, and other injustices, but is an active conspiracy to harm White people.

Paul Jackson writes that in the post-war period, “various articulations of the theme that white people are now themselves subject to an ongoing process of cultural genocide, or ethnocide” emerged among a variety of neo-fascist groups.[29] This view is a cornerstone of contemporary White Nationalism, epitomized in the work of American neo-Nazi David Lane, who published a book written while in prison whose first chapter was the “White Genocide Manifesto.”[30] Lane’s understanding of White genocide is founded on an anti-Jewish conspiracy belief that all Western nations are now secretly controlled by Jews, who are carrying out this supposed anti-White campaign.

French conspiracy theorist Renaud Camus helped popularize these notions through his 2011 book Le Grand Remplacement, which took themes from Lane and the White genocide conspiracy, stripped them of their explicit antisemitism, and provided this view with a new language.[31] The book argues that immigration policy in France, particularly the immigration of Arabs and Muslims, is an active attack on French culture. The Replacement theory sees immigration as an anti-White attempt to replace Europeans and European descendants with Black and Brown people.

Like the notion of “White genocide,” the “Great Replacement” or “Replacement Theory” helped popularize White nationalist beliefs and bring them to a much larger audience. It is explicitly rooted in a conspiracy that global elites are secretly trying to destroy White culture and White people through non-White immigration.[32] While Camus’ work did not blame Jews explicitly for this conspiracy, many have adapted it to fit within a broader anti-Jewish conspiracy framing Jews as responsible for non-White immigration.

This theory motivates political violence.[33] The Great Replacement was the name the Christchurch shooter gave his manifesto. Demographic decline was listed in the manifesto as a crisis. Several others who have committed acts of racist terrorism have written that their violence was inspired by this conspiracy,[34] including the 2018 massacre at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh.[35]

While inspiring outbursts of violence, this reframing of immigration as a conspiracy to actively “replace” White people has also become popular among a broader conservative movement, inspiring the anti-immigrant movement. A New York Times analysis of conservative media personality Tucker Carlson found that he referred to replacement theory in over four hundred episodes of his news show between 2016 and 2021.[36] Part of the popularity of this conspiracy is that it frames White people as victims while allowing different actors to be blamed for encouraging immigration. Carlson often blamed Democratic lawmakers for trying to “replace” the electorate.

Within this conspiracy, maintaining White demographic dominance is understood not as an effort to maintain White supremacy or White racial power, but to prevent annihilation and to act in racial self-defense.

At the same time that Trump was proclaiming that White South Africans suffered persecution and White Afrikaners were welcomed into the U.S. as refugees, a significant escalation of ICE raids began across the country alongside massive restrictions in refugee and immigration programs.[37] These policies are of course connected and shaped by this increasingly popular conspiracy that pernicious groups are seeking actively to replace White people with immigrants of color.

Understanding Race as a Fight for Supremacy

The concept of White genocide is linked to the idea that a race war is not only imminent but is already here. This belief shows that White nationalists don’t just believe White people and White culture are superior, but they see different racial groups in an ongoing battle for supremacy. According to this logic, there is no peaceful co-existing, no possibility of a multiracial democracy. Instead, there is an ongoing battle between distinct racial groups for supremacy.

An inordinate amount of effort within these digital spaces is focused on generating “evidence” to support this claim that a race war is under way. Various White nationalist websites will catalog lists of “ethnic crime reports,” curated lists purportedly documenting crimes carried out by people of color or Jews against White people.[38] All of these are meant to prove that White people are currently under attack from people of color, immigrants, and Jews.

This means there are profoundly different understandings of the meaning of race itself operating on the U.S. Left and the Right, and it is important to understand these differences. For decades social scientists have worked to reframe race as a social—and not a biological—construct, or offered the concept of “racial experience” to understand how race is experienced in interactions, not in biology.[39] Race, however, remains popularly understood differently. It not only remains largely seen as a biological category, something the proliferation of genetic ancestry tests no doubt reinforces, but also as a concept entwined in hierarchy.[40] And it is this inseparability of the concept of race and hierarchy that the discussion about “White genocide” brings to the fore.

Across a variety of White nationalist publications, online chatrooms, and in manifestos published by mass murderers is a consistent understanding that race is a contest for supremacy. Racist stereotypes against people of color are of course rife throughout this movement, but beyond this is a specific understanding that racial categories are not only fixed but in an ongoing fight for dominance. White nationalist publications publish ongoing lists of supposedly anti-White violence conducted by people of color, reports of an anti-White Jewish conspiracy to destroy White people are found across a broad array of White nationalist spaces, and mass shooters declare they are defending themselves through committing murder.[41] Beyond this movement, surveys show that many White Americans now believe that decreasing racial prejudice against people of color is correlated with an increase in anti-White prejudice.[42]

This understanding of race as a contest for supremacy means that changes in the racial status quo are not seen as a move towards equality but instead as a reshuffling of a hierarchy of privilege. Seeing race as inherently hierarchical means that antiracist efforts to dismantle systems of White supremacy are understood instead as a move towards persecuting White people. In this view, challenging White privilege makes White people newly vulnerable to racial oppression.

The White nationalist view of race as a contest for supremacy is held by a much broader segment of the population. Understanding these differences is a key first step to understanding the profound danger of the White nationalist lies about a race war and developing strategies for countering this trend. This is particularly relevant today as these views are motivating widespread anti-immigrant policy and action. In an increasingly racially diverse United States, these myths encourage White people to support racist policies, oppose immigration and refugee resettlement, and make defending racial power a focus of politics.

Demographic Wars

Trump’s effort to frame White South Africans as subject to racial violence follows a long history. Allowing a small number of White Afrikaners into the U.S. as racial refugees is symbolic, but it supports an influential story of White victimhood. This story reinforces a view that White people are increasingly subject to racial prejudice and oppression in the U.S. as well—and is used to justify anti-immigrant policies that restrict or block non-White immigration.

Since the launch of his first presidential campaign, Trump has consistently framed immigrants of color as a pernicious threat. In a 2015 speech announcing his presidential run, he warned of immigrants from Mexico, Latin and South America, and “probably” the Middle East crossing the border, saying, “They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.”[43] More recently, in 2023, he claimed immigrants were “poisoning the blood of our country.”[44]

The second Trump administration has sought to significantly increase deportations of undocumented immigrants and limit programs for migration to the U.S. A planned reorganization of the U.S. State Department would also create an Office of Remigration, coordinating deportations.[45] This new office would replace an office that had coordinated the movement of people into the country into an office focused on moving people out of it.[46] “Remigration” is a term popular within the European Far Right to describe efforts to deport non-European immigrants, and in the U.S., as Steven Gardiner argues, “it’s an unabashedly white nationalist idea.”[47]

Immigration restriction and deportation are part of a long history of efforts to make the U.S. a “White majority” country. A century ago, during a national resurgence of KKK activity and nativist sentiment, President Calvin Coolidge signed the Immigration Restriction Act while proclaiming, “America must remain American,” echoing a then-popular KKK phrase, “America for Americans.”[48] The law imposed a quota system for new immigrants, significantly reducing immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe targeting Jews and Catholics and making legal immigration from other parts of the world nearly impossible. This quota system was in place until a 1965 immigration law that dramatically reshaped the demographics of the U.S. Today’s anti-immigrant policies must be understood within this context as an attempt to maintain White-majority power and dominance.

The myth of “White genocide” tells a story of victims and aggressors that justifies anti-immigrant perspectives. It also leaves the actual victims of genocide, or other forms of systemic violence, outside of the story. This is a myth not only because it is false, but because it reinforces beliefs through the messages it conveys to a general audience. This contest for supremacy portends a danger for the U.S. as it stokes fears among White conservatives about changing racial demographics to incite racial backlash. National survey results show that fear of losing a privileged racial status is eroding democratic principles among White Republicans, in that many respondents say violence may be acceptable in the defense of their way of life.[49] Such fears can lead to both vigilante violence as well as support for anti-immigrant policies.

As in the photos Trump held up in his Oval Office meeting with Ramaphosa, even when the story is a lie, it still has power to impact policy and politics in profound ways.

Endnotes

[1] Reuters, “Trump’s Image of Dead ‘white Farmers’ Came from Reuters Footage in Congo, Not South Africa,” Reuters, May 22, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/trumps-image-dead-white-farmers-came-reuters-footage-congo-not-south-africa-2025-05-22/.

[2] Nandita Bose et al., “Trump Confronts South Africa’s Ramaphosa with False Claims of White Genocide,” Reuters, May 21, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/under-attack-by-trump-south-africas-ramaphosa-responds-with-trade-deal-offer-2025-05-21/.

[4] Daphne Psaledakis, Tim Cocks and Simon Lewis, “First white South Africans arrive in US as Trump claims they face discrimination,” Reuters, May 12, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/first-white-south-africans-fly-us-under-trump-refugee-plan-2025-05-12/; refer also to Tammy Bruce, “Welcoming Afrikaner Refugees Fleeing Discrimination,” U.S Department of State, May 12, 2025, https://www.state.gov/releases/office-of-the-spokesperson/2025/05/welcoming-afrikaner-refugees-fleeing-discrimination/.

[5] Farouk Chothia, “Are White South Africans Facing a Genocide as Donald Trump Claims?,” BBC, June 2, 2025, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c9wg5pg1xp5o.

[6] James Alexander Dun, “The History of White Refugee Narratives,” TIME, June 9, 2025, https://time.com/7289125/south-africa-haiti-white-refugees/. See also Kimahli Power and Jean Freedberg, “The Afrikaner Exception: Race and Strategic Dismantling of U.S. Refugee Protection under the Trump Administration,” Carr-Ryan Center for Human Rights, May 19, 2025, https://www.hks.harvard.edu/centers/carr-ryan/our-work/carr-ryan-commentary/afrikaner-exception-race-and-strategic-dismantling.

[7] Sarah Betancourt, “Trump’s Suspension of Refugee Program Leaves Advocates in Turmoil but Unsurprised,” The Guardian, January 22, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/jan/22/trump-refugee-program.

[8] Sophie Bjork-James, “Feminist Ethnography in Cyberspace: Imagining Families in the Cloud,” Sex Roles: A Journal of Research 73, no. 3 (2015).

[9] R. Sophie Statzel, “Cybersupremacy: The New Face and Form of White Supremacist Activism,” in Digital Media and Democracy: Tactics in Hard Times, ed. Megan Boler (MIT Press, 2008).

[10] Jessie Daniels, Cyber Racism: White Supremacy Online and the New Attack on Civil Rights (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2009).

[11] Statzel, “Cybersupremacy.”

[12] Sophie Bjork-James, “Racializing Misogyny: Sexuality and Gender in the New Online White Nationalism,” Feminist Anthropology, no. 1.2 (2020): 176–83.

[13] Michael I. Norton and Samuel R. Sommers, “Whites See Racism as a Zero-Sum Game That They Are Now Losing,” Perspectives on Psychological Science 6, no. 3 (2011): 215–18.

[14] Larry M. Bartels, “Ethnic Antagonism Erodes Republicans’ Commitment to Democracy,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, no. 37 (August 31, 2020) https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2007747117.

[15] Andrew Whitehead, “The Growing Anti-Democratic Threat of Christian Nationalism in the U.S.,” Time Magazine, May 27, 2021, https://time.com/6052051/anti-democratic-threat-christian-nationalism/.

[16] For more on Christian Nationalism and hierarchies see Sophie Bjork-James, The Divine Institution: The Politics of White Evangelicalism’s Focus on the Family (Rutgers University Press, 2021); For more on Christian Nationalism as a threat to democracy see Steven Gardiner, “End Times Antisemitism: Christian Zionism, Christian Nationalism, and the Threat to Democracy,” Political Research Associates, July 9, 2020, https://politicalresearch.org/2020/07/09/end-times-antisemitism; Bradley Onishi, Preparing for War: The Extremist History of White Christian Nationalism—and What Comes Next (Broadleaf Books, 2023).

[17] Manning Marable, The Great Wells of Democracy: The Meaning of Race in American Life (Basic Books, 2003), 20–21.

[18] Tal Kopan, “Donald Trump Retweets ‘White Genocide’ Twitter User,” CNN, January 22, 2016, https://www.cnn.com/2016/01/22/politics/donald-trump-retweet-white-genocide.

[19] See Cynthia Miller-Idriss, Hate in the Homeland: The New Global Far Right (Princeton University Press, 2020).

[20] J.M. Berger, Nazis vs. ISIS on Twitter: A Comparative Study of White Nationalist and ISIS Online Social Media Networks (George Washington Program on Extremism, 2016).

[21] R. Sophie Statzel, “The Apartheid Conscience: Gender, Race, and Re-Imagining the White Nation in Cyberspace,” Ethnic Studies Review 29, no. 2 (2006): 20–45.

[22] Theodore Roosevelt, “On American Motherhood,” in A Compilation of the Messages and Speeches of Theodore Roosevelt, 1901-1905, ed. Alfred Henry Lewis, vol. 1 (Bureau of National Literature and Art, 1906).

[23] Luke Baumgartner, “Where Did the White People Go?” Program on Extremism, George Washington University, April 3, 2025, https://extremism.gwu.edu/where-did-white-people-go.

[24] Baumgartner, “Where Did the White People Go.”

[25] Linda Gordon, The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition (Liveright Publishing, 2017).

[26] Gaby Del Valle, “Trad Values Meets Tech: The U.S. Right’s Pronatalist Coalition,” Political Research Associates, March 27, 2025, https://politicalresearch.org/2025/03/27/trad-values-meets-tech.

[27] Cheryl Harris, “Whiteness as Property,” Harvard Law Review 106, no. 8 (1992): 1707–91.

[28] Ian Haney-López, White by Law: The Legal Construction of Race (NYU Press, 1996).

[29] Paul Jackson, “‘White Genocide’: Postwar Fascism and the Ideological Value of Evoking Existential Conflicts,” in The Routledge History of Genocide, ed. Cathie Carmichael and Richard C. Maguire (Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2015), 304, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315719054-25.

[30] Rosa Schwartzburg, “No, There Isn’t a White Genocide,” Jacobin, September 4, 2019, https://jacobin.com/2019/09/white-genocide-great-replacement-theory.

[31] Norimitsu Onishi, “The Man Behind a Toxic Slogan Promoting White Supremacy,” The New York Times, September 20, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/20/world/europe/renaud-camus-great-replacement.html.

[32] Michael Feola, The Rage of Replacement: Far Right Politics and Demographic Fear (University Of Minnesota Press, 2024), https://www.upress.umn.edu/9781517916800/the-rage-of-replacement/.

[33] Political Research Associates, “Buffalo Massacre: An Act of White Nationalist Political Violence,” Political Research Associates, May 16, 2022, https://politicalresearch.org/2022/05/16/buffalo-massacre-act-white-nationalist-political-violence.

[34] David Bauder, “What Is ‘Great Replacement Theory’ and How Does It Fuel Racist Violence?,” PBS News, May 16, 2022, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/what-is-great-replacement-theory-and-how-does-it-fuel-racist-violence.

[35] Campbell Robertson, “The Synagogue Attack Stands Alone, but Experts Say Violent Rhetoric Is Spreading,” The New York Times, August 4, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/04/us/pittsburgh-synagogue-shooting-antisemitism-bowers.html.

[36] Karen Yourish et al., “Inside the Apocalyptic Worldview of ‘Tucker Carlson Tonight,’” The New York Times, April 30, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/04/30/us/tucker-carlson-tonight.html.

[37] Albert Sun, “Immigration Arrests Are Up Sharply in Every State. Here Are the Numbers.,” The New York Times, June 27, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2025/06/27/us/ice-arrests-trump.html.

[38] Statzel, “Cybersupremacy.”

[39] Jada Benn Torres and Gabriel Torres Colón, “Racial Experience as an Alternative Operationalization of Race,” Human Biology Open Access Pre-Prints 76 (December 2015), https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol_preprints/76.

[40] Views that race is biological have been shown to be prevalent throughout the medical profession. See Heidi L. Lujan and Stephen E. DiCarlo, “Misunderstanding of Race as Biology Has Deep Negative Biological and Social Consequences,” Experimental Physiology 109, no. 8 (2024): 1240–43, https://doi.org/10.1113/EP091491. For a discussion of genetic ancestry tests see Jada Benn Torres and Gabriel A. Torres Colón, Genetic Ancestry (Routledge, 2021).

[41] Statzel, “Cybersupremacy.”

[42] Norton and Sommers, “Whites See Racism.”

[43] TIME Staff, “Here’s Donald Trump’s Presidential Announcement Speech,” TIME, June 16, 2015, https://time.com/3923128/donald-trump-announcement-speech/.

[44] Ginger Gibson, “Trump Says Immigrants Are ‘Poisoning the Blood of Our Country.’ Biden Campaign Likens Comments to Hitler,” NBC News, December 17, 2023, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2024-election/trump-says-immigrants-are-poisoning-blood-country-biden-campaign-liken-rcna130141.

[45] Charisma Madarang, “Trump Admin Moves to Create ‘Remigration’ Office to Supercharge Deportations,” Rolling Stone, May 30, 2025, https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/trump-remigration-office-immigration-deportations-1235350960/.

[46]Andrew Roth, “State Department Ramps up Trump Anti-Immigration Agenda with New ‘Remigration’ Office,” The Guardian, May 30, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/may/30/state-department-plans-office-of-remigration-to-support-trump-agenda.

[47] Steven Gardiner, “‘Remigration’ Is American for ‘Ethnic Cleansing,’” Religion Dispatches, June 5, 2025, https://religiondispatches.org/remigration-is-american-for-ethnic-cleansing/.

[48] Devin Naar, “The Regional Origins of America’s First Comprehensive Federal Immigration Law,” TIME, July 9, 2024, https://time.com/6990567/1924-act-washington-state/.

[49] Bartels, “Ethnic Antagonism.”