Over the past four decades, I have learned that the majority of the work to build the worlds we want happens outside of the structures that manufacture and preserve existing relations of power. I’ve developed a deeper awareness and understanding that we must step beyond what we know to experiment with, build, and practice new ways of being in relationship with each other and the planet.

Practicing New Worlds (AK Press, 2023)

Yet, as conditions worsen and urgency increases, as millions are increasingly mired in economic and climate crises while billionaires bank on our suffering, as the Right rises around the globe and comes for our throats with a clear intention to obliterate communities I am part of and care deeply about, the destruction of so much of the planet we call home looms large, and as police, state, and white-supremacist violence and Repression occurs when public or private institutions—such as law enforcement agencies or vigilante groups—use arrest, physical coercion, or violence to subjugate a specific group. Learn more intensify and multiply, it feels harder and harder to try on different strategies to resist and persist. It feels riskier to experiment; to reach for different ways of thinking, being, and relating; to imagine and create conditions for something new to emerge. The more pressure we are under, the more urgency, uncertainty, and fear we face, the stronger our instincts are to cling to the familiar. Under pressure, we are more likely to double down on strategies that have largely failed in the past, and turn to the institutions and structures that manufacture, produce, and sustain the current order in the hopes of changing them—or of at least staving off the worst of what’s to come. We fight harder but continue to fight in the ways we know.

This is precisely the time when we most need to critically examine the ways we are seeking to make change, and to explore where and how we need to shift our approach.

This moment calls on us to practice new ways of relating, new forms of governance, and new modes of being that enable the worlds we want to emerge instead of relying on top-down, law and policy-based strategies that are mired in the illusion that we can change systems and institutions doing exactly what they were created to do: produce and maintain societies that promote extractive accumulation by the few at the expense of the many and of the planet, structured by laws, policies, and institutions that distribute life chances through surveillance, policing, punishment, and exclusion.

“This moment calls on us to practice new ways of relating, new forms of governance, and new modes of being that enable the worlds we want to emerge.”

Philosopher, organizer, and beloved movement elder Grace Lee Boggs would often begin conversations by asking, “What time is it on the clock of the world?” According to Grace, one answer is that “in the midst of this epochal shift, we all need to practice visionary organizing.” For her, that meant moving beyond protest organizing: “Instead of viewing the US people as masses to be mobilized . . . we must have the courage to challenge ourselves to engage in activities that build a new and better world by improving the physical, psychological, political, and spiritual health of ourselves, our families, our communities, our cities, our world, and our planet.”9 In her view, visionary organizing “begins by creating images and stories of the future that help us imagine and create alternatives to the existing system.”10

In The Next American Revolution: Sustainable Activism for the Twenty-First Century, Grace writes with Scott Kurashige: “The tremendous changes we now need and yearn for in our daily lives… cannot come from those in power or from putting pressure on those in power. We ourselves have to foreshadow or prefigure them from the ground up.”11 In other words, we need to stop looking exclusively to the same places we always have looked, doing the same things we have always done, being the same people we have always been. Instead, we must seek out new ways of thinking, doing, and being in everyday actions, with the intention of shifting large and complex systems and relations of power. We need to seek out as many portals as we can find into futures we cannot currently imagine and practice them every day.

I have come to believe that emergent strategies offer important clues to help us to find new paths forward, to step outside of what we know and into the futures we want to create, to survive, and to resist the futures racial capitalism and Right-wing forces seek to make inevitable.

“We need to stop looking to the same places we always have looked, doing the same things we have always done, being the same people we have always been.”

Emergent Strategy and emergent strategies

adrienne maree brown’s book, Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds, has served as an introduction to emergent strategies for hundreds of thousands of people, including me. (I use Emergent Strategy to refer to adrienne maree brown’s book of that name, and emergent strategies to refer to the broader body of work the book draws on.) It summarizes a broader set of ideas about how to create, shift, and change complex systems—including human society— through relatively simple interactions. Emergent strategies, as adrienne describes them, focus on starting small and making space for and learning from uncertainty, multiplicity, experimentation, adaptation, iteration, and decentralization.

These ideas are not new—Emergent Strategy draws on a much deeper body of work rooted in the workings of the natural world, Indigenous lifeways, complexity science, change theory, Grace Lee Boggs’s later writings, the work of the Complex Movements Collective, and the observations of scholars and organizers across generations. In many ways, Emergent Strategy distills and invites us to hone key principles already at play in effective organizing efforts and movements. Emergent strategies, by definition, require attention to emergence—what becomes possible under certain conditions when we:

- start small and focus on critical connections,

- build decentralized networks,

- iterate and adapt with intention, and

- cooperate toward collective sustainability,

rather than trying to control or impose change through law, policy, and other top-down strategies.

While this approach may feel counterintuitive given the scale of the problems we face and the growing political power of authoritarian forces, change scholars Margaret Wheatley and Deborah Frieze argue that emergence has made large-scale resistance and societal shifts possible. According to them, these shifts happened through “many local actions and decisions, most of which were invisible and unknown to each other, and none of which was powerful enough by itself to create change. But when these local changes coalesced, new power emerged. What could not be accomplished by diplomacy, politics, protests, or strategy suddenly happened.”12

“Emergent strategies invite us to act based on shared values and principles at a smaller scale.”

…

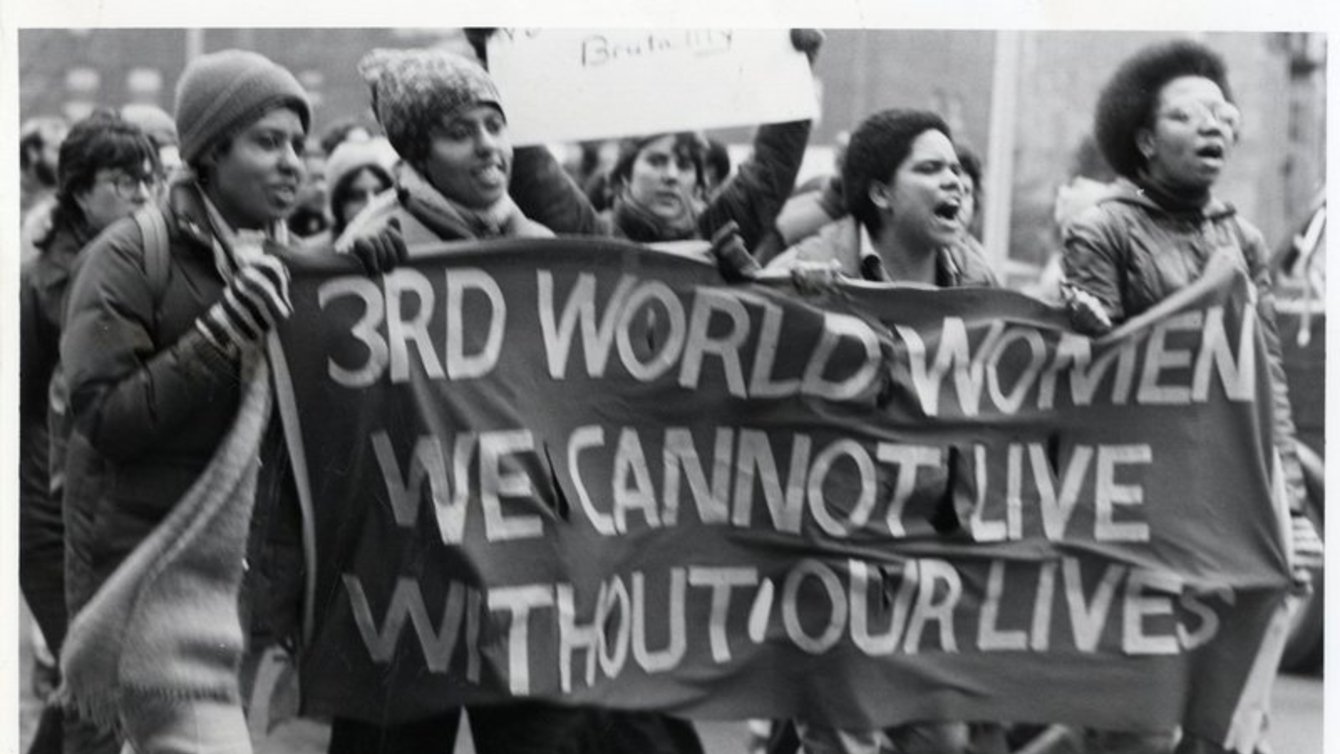

Practicing emergent strategies doesn’t mean that we no longer try to affect large systems. It “doesn’t mean eschewing the systemic for the interpersonal or vice versa. Emergence is an invitation to hold a dual focus.”14 As someone living in a time of climate collapse, mounting A form of far-right populist ultra-nationalism that celebrates the nation or the race as transcending all other loyalties. Learn more , and rising rates of white-supremacist, gender-based, homophobic, transphobic, colonial, and anti-Black violence, I am painfully aware that large systems are increasingly constraining possibility at every scale. As a Black feminist, I am committed to what the Combahee River Collective Statement describes as “the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of The use of violence, intimidation, surveillance, and discrimination, particularly by the state and/or its civilian allies, to control populations or particular sections of a population. Learn more are interlocking,” and on the premise that “if Black women were free that would mean everyone else would have to be free because our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all systems of oppression.”15 None of the changes I want to see in the world are possible without eliminating a global economic system built on racial capitalism and the structural violence it requires and produces along the axes of race, gender, sexuality, disability, class, and nation, operating in the lives of Black women, trans and gender nonconforming people, and our communities everywhere. By definition, this requires large-scale, systemic change.

The knowledge that what happens at the small-scale replicates, coalesces into, and shapes larger social structures and systems simply shifts the primary focus of transformation to our relationships, interactions, networks, and communities instead of strategies that rely exclusively on mass mobilization and top-down legislative and policy initiatives. Emergent strategies invite us to act based on shared values and principles at a smaller scale, and to connect our actions across time and space into networks with the power to shape complex systems. They remind us that we are constantly learning and adapting to changing conditions at the individual and collective levels. They point to critical guidance offered by the natural world on building resilience under pressure through decentralization, cooperation, and interdependence. They urge us to ask generative questions; move beyond binaries; value uncertainty; practice while learning from our mistakes; and to create more possibilities. They invite us to engage our radical imaginations and to center joy and pleasure in our efforts.

…

“To fight a competing world vision that is rapidly spreading in part through what could be characterized as emergent strategies, we need to at least understand and practice them ourselves.”

Why Emergent Strategies Matter in a Time of Fascism

Even if you are not convinced that emergent strategies can play an important role building toward the worlds we want, there are still important reasons to learn about them. In fact, I have come to believe that we can’t afford to not to be emergent strategists in this time—because emergent strategies are part of how we got to where we are. Over the past six decades, the Often used interchangeably with Christian Right, but also can describe broader conservative religious coalitions that are not limited to Christians. Can include right-wing Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Mormons, and members of the Unification Church of Sun Myung Moon. Learn more has leveraged the power of relatively small interactions—in church basements and prayer circles, over harvest and coffee—to shape the systems and conditions we are now living. While the use of law, policy, political parties, think tanks, and judicial appointments to advance Right-wing agendas is more visible, these strategies represent the tip of the iceberg in terms of how the Right built the power they are now exercising in an attempt to dominate what they describe as the seven mountains or pillars of society: economy, education, family life, religion, media, culture, and government.19 While our collective focus has rightly been on authoritarian, top-down Christian evangelical efforts, led by charismatic leaders, to pass legislation to ban abortion and gender-affirming care, attempt to eradicate the public existence of trans and queer people, to take over and overturn systems of government, and to impose a white-supremacist, patriarchal Christian In the classical definition, a system in which governmental leaders are clergy. Learn more , there is much more at play.

The A movement that emerged in the 1970s encompassing a wide swath of conservative Catholicism and Protestant evangelicalism. Learn more has adopted the strategy of calling on its followers to “go and make disciples” and to “invade” each of these seven arenas with the intention of shifting larger systems further toward Both a system of beliefs that holds that White people are intrinsically superior and a system of institutional arrangements that favors White people as a group. Learn more and cisheteropatriarchy. Supporters are encouraged to advance theocratic values through critical connections: in their workplaces, faith communities, social media posts, and conversations with families and friends.20 Neo-Nazis are similarly deploying decentralized strategies reliant on small groups of people to form “a web, instead of a chain of command.”21 ¡No Pasarán!: Antifascist Dispatches from a World in Crisis contributors Emmi Bevensee and Frank Miroslav write, “One of the most concerning developments is the shift by various strands of fascism into becoming more horizontal and to using distributed organizing mechanisms . . . There are a number of reasons this kind of distributed white terror is becoming more popular; the most obvious of which is that it works.”22 In a particularly alarming turn, the Patriot movement is bastardizing “dual power” approaches that originate in revolutionary struggles of the Global South and focus on both challenging state power and building prefigurative community institutions.23 In the Patriots’ case, they do so by creating militias and common law courts that prefigure the dictatorship they seek to impose on broader society.24 A term from the 2010s to describe far-right activists rooted in paleoconservatism with more explicit racism & xenophobia. Learn more groups are likewise seeking to dismantle centralized states while upholding patriarchal non-state “tribal” systems rooted in male dominance.25 In other words, Right-wing movements are also manifesting decentralized, adaptive, and iterative approaches to shaping the world that build on critical connections and networks to shift larger systems.

As a result, as organizer and strategist Suzanne Pharr, longtime student of Right-wing, white-supremacist movements, puts it, “They are so pervasive as to be obscured and normalized to the extent that they are simultaneously everywhere all the time and difficult to detect.”26 Like a virus, they infect communities, replicate themselves, and spread.27 To resist, Pharr calls us to engage in local work aimed at transforming individuals and communities, to recognize that “the bridges we build one by one between individuals are the strongest,” to understand our struggle as one of fundamental values, and to move with the knowledge that “every step toward liberation must have liberation in it.”28 As organizer Shane Burley writes in ¡No Pasarán!, “The antidote to fascism in all its manifestations is community-building.”29 Emmi Bevensee and Frank Miroslav argue that, “Whereas fascists use complexity to promote their violent and overly simplistic worldview, antifascists can use complexity to cultivate richly diverse and evolving networks of resistance.” In other words, to fight a competing world vision that is rapidly spreading in part through what could be characterized as emergent strategies, we need to at least understand and practice them ourselves.

- Endnotes

9. Grace Lee Boggs with Scott Kurashige, The Next American Revolution: Sustainable Activism for the Twenty-First Century (Oakland: University of California Press, 2012), 72.

10. Boggs and Kurashige, The Next American Revolution, xxi, 72.

11. Boggs and Kurashige, The Next American Revolution, 72.

12. Margaret J. Wheatley and Deborah Frieze, “Using Emergence to Take Social Innovations to Scale,” The Berkana Institute, 2006, https://margaretwheatley.com/articles/emergence.html.

14. Sage Crump, A Cultural Strategy Toolkit, https://www.cultural strategy.space. See also Boggs and Kurashige, The Next American Revolution, xvii.

15. Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017).

19. For more information on The theocratic idea that Christians are called by God to exercise political and cultural dominion over society. Learn more , please see Frederick Clarkson, Political Research Associates, “101: Dominionism,” Political Research Associates, November 4, 2022, https://politicalresearch.org/2022/ 11/04/101-dominionism; and Imara Jones #AntiTransHateMachine, Translash Media, https://translash.org/antitranshatemachine.

20. Elle Hardy, “The ‘Modern Apostles’ Who Want to Reshape America Ahead of the End Times,” The Outline, March 19, 2020, https://theoutline.com/post/8856/seven-mountain-mandate-trump-paula-whi…;

21. Matthew N. Lyons, “Three-Way Fight Politics and the US Far Right,” in ¡No Pasarán! Antifascist Dispatches from a World in Crisis, ed. Shane Burley (Chico, CA: AK Press, 2022). See also Matthew N Lyons, Insurgent Supremacists: The US Far Right’s Challenge to State and Empire (Montreal: Kersplebedeb, 2018).

22. Emmi Bevensee and Frank Miroslav, “It Takes a Network to Defeat a Network: (Anti)Fascism and the Future of Complex Warfare,” in ¡No Pasarán! Antifascist Dispatches from a World in Crisis, ed. Shane Burley (Chico, CA: AK Press, 2022).

23. For more on dual power strategies, please see Andrea J. Ritchie and Mariame Kaba, No More Police; Andrea J. Ritchie, “Abolition and the State: A Discussion Tool,” Interrupting Criminalization (New York: Interrupting Criminalization, 2022), https://www.interrupting criminalization.com/abolition-and-the-state; Mijente, Building Power Sin, Contra, y Desde el Estado, video, April 12, 2022, https:// mijente.net/2022/04/building-power-sin-contra-y-desde-el-estado, and Paula X. Rojas, “Are the Cops in our Heads and Hearts?,” The Scholar and Feminist Online 13, no. 2 (Spring 2016), https://sfonline .barnard.edu/paula-rojas-are-the-cops-in-our-heads-and-hearts, reprinted from The Revolution Will Not Be Funded, ed. INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015).

24. Lyons, “Three-Way Fight Politics and the US Far Right.”

25. Lyons, “Three-Way Fight Politics and the US Far Right.”

26. Suzanne Pharr, Transformation: Toward a People’s Democracy (Blacksburg, VA: Virginia Tech Publishing, 2021), 13.

27. Emmi Bevensee and Frank Miroslav call this process “stigmergy,” a mechanism of indirect coordination in which an action by one individual “stimulates the performance of a succeeding action by the same or a different agent.” This phenomenon could describe, for instance, copycat mass shootings or attacks on spaces where An umbrella acronym standing for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning. Learn more people are gathered. Emmi Bevensee and Frank Miroslav, “It Takes a Network to Defeat a Network: (Anti)Fascism and the Future of Complex Warfare.”

28. Pharr, Transformation, 19, 368.

29. Shane Burley, “Building Communities for a Fascist-Free Future,” in ¡No Pasarán! Antifascist Dispatches from a World in Crisis, ed. Shane Burley (Chico, CA: AK Press, 2022).