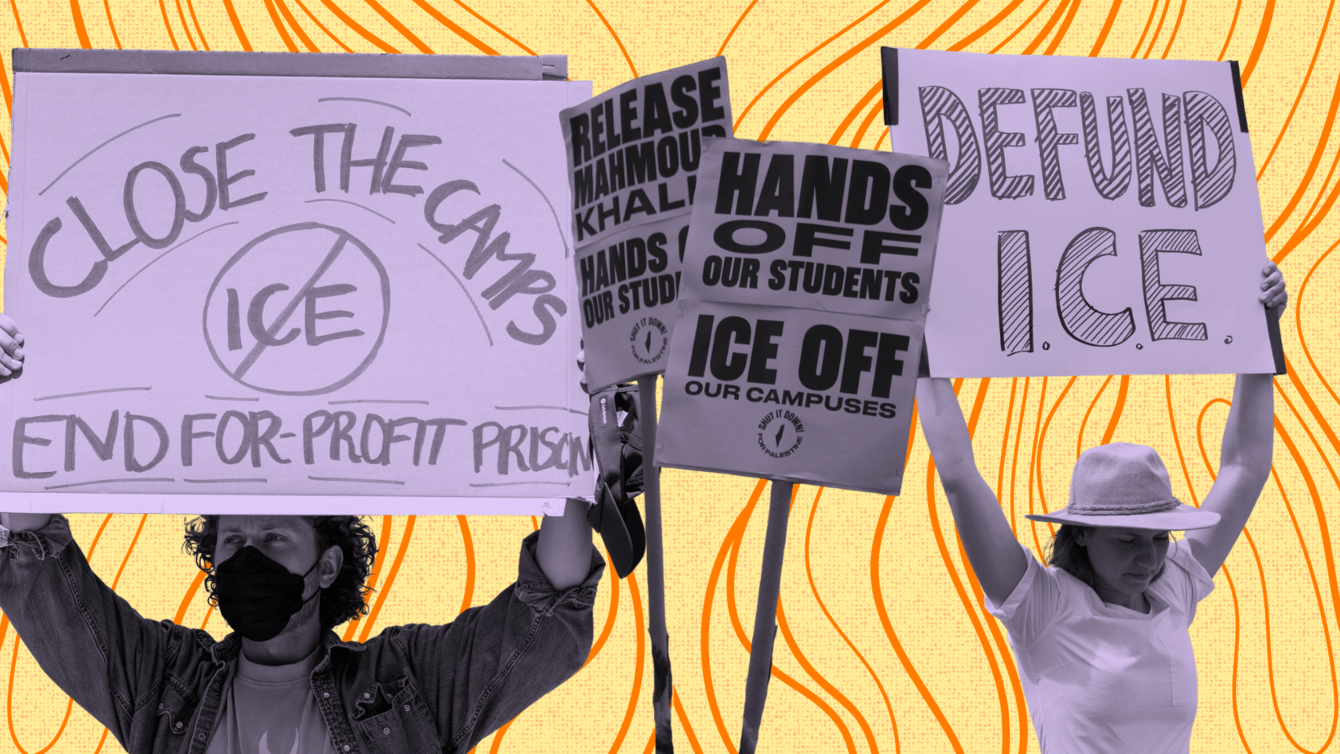

The first few months of President Trump’s second term has seen a massive escalation in the targeting and imprisonment of immigrants—including renditions to prisons abroad, the abduction of Palestine solidarity activists, and militarized ICE raids on communities.

The administration’s immigration policy relies on decades-old tools—notably, a bill authored by the A term used to describe organizations, movements, ideas, and policies that oppose immigrants and immigration. Learn more movement and signed by President Bill Clinton that created the contemporary deportation machine in the 1990s.[Footnote 1] But the bipartisan expansion of criminalization, detention, and deportation in the decades since has also spurred vibrant resistance at the intersections of immigrant rights, racial justice, and prison abolition.

In Unbuild Walls: Why Immigrant Justice Needs Abolition (Haymarket, 2024), Silky Shah, executive director of Detention Watch Network, presents a history of the immigrant justice movement, drawing on over twenty years of organizing against the entangled systems of immigration enforcement and the prison industrial complex. Immigrant justice, Shah argues, requires embracing abolitionist principles, to move beyond “comprehensive immigration reform” and other efforts that “[ignore] the economic, political, and racial implications of why our immigration enforcement system operates as it does.”[Footnote 2]

Unbuild Walls contains vital context and strategic insights for how to approach the Trump administration’s anti-immigrant authoritarianism. Shah spoke with PRA in July 2025 about developments over the last six months, lessons from decades of organizing, and, of course, the need for an abolitionist approach to immigration that centers ending the criminalization, detention, and deportation of people. This interview is lightly edited for length and clarity.

Unbuild Walls: Why Immigrant Justice Needs Abolition

Haymarket, 2024

PRA: What inspired you to write Unbuild Walls?

Silky Shah: I’ve been organizing around immigration since 9/11. I organized in Texas to stop the prison boom after DHS was created. I had connected with groups doing work around the criminal legal system and the prison industrial complex, and people connected with Critical Resistance started to talk about abolition. I embraced the idea and by the time I was thinking about writing this book in 2021, I was really compelled by the history of this work and the vision it presents.

Abolition as a lens and strategy became clearer to me as our strategies against immigration enforcement and detention sharpened in relationship to the Black Lives Matter movement and how much further we could go because of that deeper reckoning with racist policing and mass incarceration. We could do and did so much more. We won a lot of campaigns, but when Biden came in, things started to falter. There were many critical lessons that made it clear why abolition was an essential tool as we figured out how to curb immigrant detention and move away from this model. It felt like a time to offer those lessons.

“The last three decades [have] normalized immigration detention and deportation, making it possible for the Trump administration to weaponize the system and use it as a testing ground for authoritarianism.”

We’ve seen an expansion of literal and metaphorical walls since Unbuild Walls was published. How would you situate the last six months in the intertwined evolution of mass incarceration and immigration enforcement detailed in the book?

With the last six months, it’s hard not to think about the six months that came before. Especially the 2024 election cycle and how so many Democrats capitulated to the Republicans on immigration policy and narratives. They reinforced a lot of Republican frames: Blaming a person or group wrongfully for some problem, especially for other people’s misdeeds. Scapegoating deflects people’s anger and grievances away from the real causes of a social problem onto a target group demonized as malevolent wrongdoers. Learn more immigrants, pushing the idea that immigration is about public safety, harming many years of fighting for immigrant communities. This culminated in January 2025 when Republicans passed the Laken Riley Act[Footnote 3] with Democrats’ support. They exploited a tragedy to stoke a moral panic and further extend state control. That bill was the biggest expansion to mandatory detention policy since the 1990s and it set us up for what we’ve been negotiating for the last six months.

Trump’s signing of the Laken Riley Act was followed by executive orders and policy shifts.[Footnote 4] Some were expected, like expanding detention using private prisons and county jails. They were already signaling this and that they wouldn’t be a check on how detention centers are run. Others were unexpected. The plan for Guantánamo was a bit shocking. It’s been used for interdiction, stopping new migrants—but transferring people currently in the U.S. to Guantánamo for immigration proceedings was unprecedented. That was the slippery slope towards sending people to a mega prison in El Salvador. Similarly, there’s the detention of students who express solidarity with Palestine, who were disappeared from their communities.

By March the El Salvador renditions and student detentions revealed how much the last three decades had normalized immigration detention and deportation, making it possible for the Trump administration to weaponize the system and use it as a testing ground for authoritarianism.[Footnote 5]

It’s been accepted for so long that many people don’t deserve due process, and since 1996, it’s been baked into the law. Recent arguments that “they’re not getting due process,” are hard for immigrant justice organizers who have long seen that immigrants haven’t received due process in many ways. But now the scope is expanded. Targeting people for thought crimes and offshoring people to horrible conditions in El Salvador has made people scared.

This weaponization of the system portends very scary things. We must push back to make sure this isn’t normalized.

“The strategy of ‘good’ immigrant versus ‘bad’ immigrant ultimately targets all immigrants. We knew that would happen: As abolition teaches us, that’s how the system works. If you accept that some people deserve such treatment, they’ll expand who’s deserving.”

What do these escalations tell us about the administration’s anti-immigrant goals and strategy? What impacts are you seeing for immigrant communities and social justice movements more broadly?

These escalations purport to fulfill campaign promises while instilling fear and getting immigrants to self-deport. People are scared. Kids aren’t going to school or they’re trying to avoid public spaces. There’s a long history of U.S. militarization, policing, and imprisonment that’s deeply tied to our political economy, but for the everyday person this is a marked shift. What will speaking out against this mean? How will this affect us? It feels like that creeping authoritarianism.

At the same time, people are paying attention. They’re doing know your rights trainings and working to stop ICE from intervening in local areas. They aren’t flinching in supporting their immigrant community members. We’re all in a tenuous space together, trying to push back and gearing up for it getting worse. It’s only been six months.

The merger of the criminal legal system and immigration enforcement has been so successful in hiding the system. Under the Obama administration, deportations rose significantly because of that intentional merger. We pushed back by exposing those connections, amid a broader racial justice reckoning led by Black Lives Matter.

The government is still using the criminal legal system. Anyone with a severe criminal conviction is usually turned over to ICE. That’s the reality. The lie they’re telling you is that they’re going after the “worst of the worst,” but that’s why abolitionists are clear that we must fight for everyone. The strategy of “good” immigrant versus “bad” immigrant ultimately targets all immigrants. We knew that would happen: As abolition teaches us, that’s how the system works. If you accept that some people deserve such treatment, they’ll expand who’s deserving.

How do you balance abolitionist goals with movement and institutional energy directed towards reforms presented as strategic harm reduction in response to anti-immigrant attacks?

Social movements often get siloed without seeing the bigger picture of the work done. So, I may have critiques of certain approaches without fully realizing that even if an organization doesn’t share the same end goal, some of their work was important to moving an abolitionist strategy forward, by opening space or bringing people in.

Some people have accepted the calculation that if we make the case for the “good” immigrant, trading off more border militarization and criminalization, that’s worth it. But folks who work on detention or enforcement understand the problem with that logic. On the ground, they see the interconnections in their work and are looking to put the pieces together to strategize and organize around them. That was a great thing that came out of writing this book. It helped me feel less siloed. That’s what we need to do to work through tensions between abolition and reform. Instead of making assumptions, we need to work with people to think through the impacts of reform. There’s an opportunity in people seeing the system for what it is. I think this moment under Trump 2.0 is the time for it.

“People who care about immigration should understand the prison system. The growth of prisons over the last forty years enabled the ramping up of immigration detention.”

Just days ago Congress passed the largest allocation for immigration enforcement and detention ever. Can you describe the scale of some of these changes and their implications?

There are things we know and things we don’t know. What we know is that “traditional” detention—the use of county jails, private prisons, all of that—is going to expand. We’ve already seen that. In Florida, all county jails now have a contract with ICE.[Footnote 6] The U.S. Marshals have some 1,200 contracts to work with county jails across the country and ICE is already using some of those facilities. Much of what I’m arguing in the book is that people who care about immigration should understand the prison system. The growth of prisons over the last forty years enabled the ramping up of immigration detention.

Likewise, immigration enforcement’s shifting terrain is starting to change U.S. prisons and policing. We need to understand these intersections. Trump has threatened to send U.S. citizens currently in the Bureau of Prisons to El Salvador too. We’re anticipating more uses of military bases and makeshift camps, like the Everglades detention camp expansion they’ve deemed “Alligator Alcatraz.” We’ll likely see more of that.

What we don’t know includes things like: Will they send more people offshore? Will they send more people to third countries like South Sudan, which we saw the Supreme Court recently allow? What other strategies will the Court support? [Ed. note: Following the Supreme Court ruling, ICE issued a memo allowing officers to deport immigrants to third countries without meaningful assurances they will be safe from persecution and torture.[Footnote 7] ]

We’re concerned that this money will be used to ramp up the detention system permanently. We’ve seen ICE use this ratcheting strategy of overspending their detention budget and pulling money from FEMA and other agencies to go from 40,000 to 45,000 beds, to get Congress to bail them out and increase their funding. How will this 45 billion dollars [for new detention beds] be spent over four years? If the detention system’s capacity grows to 100,000 beds, does that help ICE continue to expand through increased funding?

Your book is also a personal and A mass movement that seeks to transform society and challenge existing power relationships by means other than (but often including) the political electoral process. Learn more history of resistance drawing from over twenty years of organizing campaigns to end detention and deportation. What are some insights from that work for organizing under the current regime?

For years I worked in Texas and nationally to stop the expansion of immigration detention. Not much happened in the way of ending detention contracts or stopping a new detention center. Then, we had openings and started to win campaigns. We were ready for it. We spent years doing local work to shift narratives and understand the relationship between immigration and mass incarceration. And we started to win. I hold on to that every day right now. It was a major reason why I wanted to write about it.

“We don’t have to accept as permanent what we have been dealt. We can fight back. The Right’s going after sanctuary policy and building more detention in response to our organizing.”

We have former DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas saying detention is overused.[Footnote 8] He doesn’t say something like that in a vacuum. He says it because conditions are shifting with local elected officials responding to movement pressure, leading to places like Illinois[Footnote 9] and Oregon[Footnote 10] having no [dedicated] detention [facilities] anymore.[Footnote 11] These are huge, significant wins. We’ve done it before and can do it again.

We don’t have to accept as permanent what we have been dealt. We can fight back. The Right’s going after sanctuary policy and building more detention in response to our organizing. It’s not like we win and then we’re done. These are dynamic campaigns that will continue and evolve based on our political conditions. There’s a lot of possibility, but we must stay vigilant in how we do this work, holding onto the wins while pushing beyond them.

As you note in the book, “the truth is that we have already begun making abolition every day.”[Footnote 12] Something to keep in mind this during such a daunting time.

It’s hard because we built those openings in 2020, when people believed more was possible. That feels far away now. Many people are accepting the frames of criminalization, crime, and disposability, making abolitionist scholarship and writing even more important. This is a time for political education and challenging those ideas—not giving in because of how narratives about public safety and national security are moving. For many years, my work has been about fighting for that person who’s considered disposable, the “bad immigrant.” I’m still reckoning with how much harder this is without a pro-immigrant narrative, even as others lean into notions of immigrant “innocence” and “productivity.” But we shouldn’t reinforce narratives that lend themselves to personal prejudices—we must really think about how these systems work.

Instead of positioning immigrants as exceptional people who are better than everyone else, we need to understand these attacks as part of the administration’s strategy for distracting us from real problems. We need to see that we’re all in this together. Otherwise, they can use anti-immigrant narratives to exploit people’s anxieties about our health care and housing crises, and the lack of social safety nets. We need to see immigration in a more expansive way, not just the enforcement piece or how DC lobbyists have positioned comprehensive immigration reform. Immigration is connected to so many issues. When we make conditions for people in the U.S. better, we make conditions for immigrants better.