Until 2012, City College of San Francisco (CCSF) was widely recognized as one of the country’s top community colleges. Founded in 1935 as the San Francisco Junior College, at its peak, it served more than 100,000 students a year in degree and non-degree programs, and touched virtually every city resident either directly or indirectly. People’s grandparents or children went there, and its English as a Second Language classes and peer support programs for various groups—from An umbrella acronym standing for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning. Learn more people to the prison re-entry population—were woven into the community fabric. Its open admission policies made it a beacon, a highly valued San Francisco asset.

But not everyone was pleased with the college’s progressive open access admissions or inclusive faculty governance policies. After 77 years, CCSF found itself in the crosshairs of the regional Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges (ACCJC), threatened with sanctions that could have completely shuttered the school if administrative changes were not quickly made. As Marcy Rein, Mickey Ellinger, and Vicki Legion write in FREE CITY! The Fight for San Francisco’s City College and Education for All, the ACCJC’s finding—that CCSF “suffered from a lack of accountability as well as institutional deficiencies in the areas of leadership”—sent shock waves through both CCSF and the entire San Francisco community.

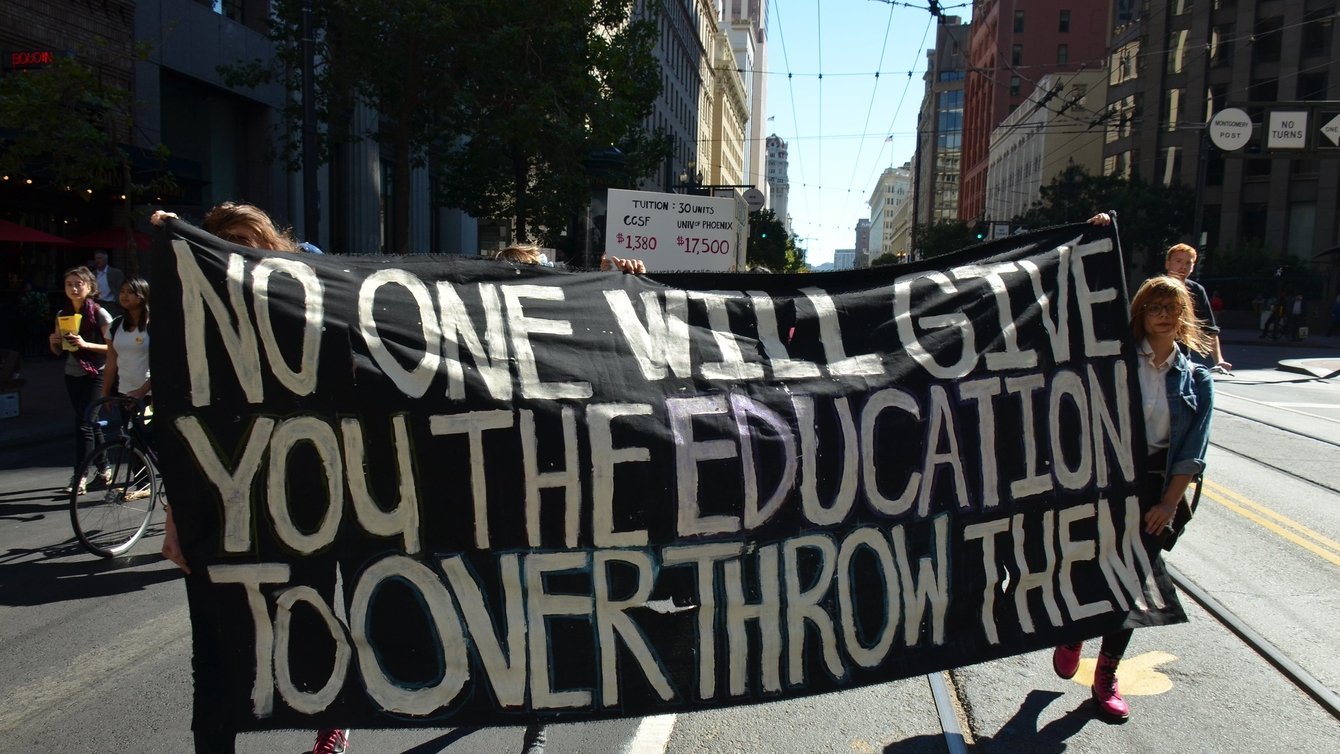

The resultant five-year movement to “Save City College” involved a wide swath of constituencies and tactics: frequent public demonstrations and picket lines; campus teach-ins; sit-ins at a college administration building and at City Hall; separate lawsuits by the City Attorney and the union representing college faculty; and ballot initiatives to ensure consistent funding for the beleaguered school—enough, in fact, to make it tuition-free for San Francisco residents.

But in addition to this victory—and the free tuition program that became known as Free City—as activists, students and faculty coalesced and mobilized, they learned that the assault on CCSF was not unique. In fact, they learned that the ACCJC’s unexpected attack on City College was part of a broader assault on public education, with the same group of venture philanthropists and corporate foundations targeting CCSF also working to remake public K-12 schools, colleges, and universities throughout the country. PRA spoke with the authors of FREE CITY! this May.

PRA: California’s Master Plan for Public Education, passed in 1960, established a tiered system of education in the state. How does that work?

Mickey Ellinger: The Master Plan was state legislation that passed as a way to meet the demand for public higher education after World War II. California was a rich state and an industrial powerhouse that needed a technologically competent workforce. At the same time, the prestigious University of California was concerned about being swamped by the masses, so the Master Plan established three tiers—the University of California, California State University, and California Community Colleges—with different admission criteria for each. Although the community colleges were always badly underfunded, at one-half of what the elite UC system allocated for each student, they were to be open to anyone who, in the words of the Master Plan, “[could] benefit from instruction.”

Vicki Legion: In many ways the Master Plan set forth a generous vision, with an open door and free tuition for anyone over the age of 18, and CCSF ran with it. The college created a huge, and high quality, English as a Second Language (ESL) program which was, and is, incredibly important. San Francisco is still a city of immigrants. City College trains the city’s cooks and nurses, health care interpreters and childcare workers. And it prepares people to transfer to university.

But the miserly funding for community colleges showed. UC-Berkeley, for example, has babbling brooks, marble halls, and clean bathrooms. SF State has Soviet-style ugly architecture and funky bathrooms, but nice grounds. City College has weeds growing up through the sidewalk, endlessly-broken bathroom stalls, and close to zero amenities.

Marcy Rein: Approximately three-quarters of Black and Latinx students who attend classes after high school in California start at a community college; statewide, community college fees are much lower and students have been able to attend part-time while working.

“Austerity is always about priorities. One of the ways that capitalism tries to stabilize itself is by shrinking the public sector and outsourcing, which siphons resources to private interests.”

PRA: Why do you think the ACCJC wanted to shrink or close CCSF?

Legion: Austerity is always about priorities. One of the ways that capitalism tries to stabilize itself is by shrinking the public sector and outsourcing, which siphons resources to private interests.

The attack on public K-12 education came first. The public was constantly told that standardized testing was essential, charter schools were a great alternative to regular public schools, and that unionized teachers were lazy and greedy. After the Great Recession of 2008, these ideas were extended to public community colleges.

Entities like the Lumina Foundation, which was established in 2000, have been choking off the community college system so that it now only serves a fraction of the students who’d like to attend. Lumina’s model programs require students to attend full time, which means most won’t be able to work and go to school simultaneously. This is one way to reengineer the system: push out the majority of working-class and Black and Brown students, and increase borrowing by those hellbent on getting a degree.

Rein: It wasn’t only City College. The entire California community college system is being shrunk. Between 2008 and 2019, student enrollment dropped by about 20 percent, even as the state population increased by close to eight percent. There was also a reduction in course offerings, and an effort to put students on a rigid path of classes that must be taken in sequence. It’s also an attack on teacher pay and benefits. CCSF faculty are unionized and part-time faculty receive health insurance and other benefits, so this is a clear attack on public sector unions. ACCJC supported the policy shift away from open access towards the shrunken college, ironically called the Student Success Model.

PRA: Besides the Lumina Foundation, are other foundations and companies working to push the anti-public-education agenda?

Rein: We call these “philanthro-capitalist foundations” because their giving serves the interests of the industries that fund them. Lumina is the most central. It was started with funds from the student loan industry. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is another name that people might recognize. These foundations fund a whole constellation of think tanks and advocacy groups to devise and push the policies. Another entity, the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), is a notorious right-wing legislation mill and has produced model bills to, among other things, push full-time attendance at community colleges.

PRA: Although many San Franciscans have deep ties to City College, the school also has critics. How did this complicate the coalition-building?

Legion: Initially, community support was paralyzed because of a struggle between two views of what was going on at City College. Some community leaders, faculty, and students felt that City College was a racist institution. They cited inadequate learning conditions, racist attitudes among some of the disproportionately White faculty, and very long sequences of remedial courses that trapped students of color. They thought the accreditation sanction could be used to force changes at the college, somewhat parallel to the notion that standardized tests could be used to force changes in K-12 schooling. A vigorous debate took place between this view and the one that opposed the sanctions as a cudgel to force CCSF to accept the “reform” agenda.

Jobs with Justice San Francisco convened a listening process that explored both questions of equity and the political roots of the accreditation attack, which strengthened the community coalition in defense of CCSF.

“Still, there’s been a shift in consciousness since the campaign began nine years ago. The campaign allowed for a great deal of leadership development. There is a lot of experience being carried forward and we have a better understanding of the root causes of the attack.”

PRA: I was shocked that the ACCJC seemed exclusively focused on administrative issues, and not on the quality of classes being offered.

Rein: Data showed that the college’s academics were excellent. The commission’s objective was not to criticize the teaching, but to curtail the college’s internalized commitment to open access. You have to ask who stands to gain from this. We believe it’s three groups: the student loan industry; for-profit colleges, which compete with community colleges for career-training students; and the ed-tech industry, since online classes are being promoted as more efficient than in-person classes. In San Francisco we also saw the real estate industry play a role because City College owns valuable [property] in a land-hungry city.

PRA: How important was litigation?

Rein: The legal component was significant for organizing. An injunction kept the college open and gave the organizers more time to do their work. The trial also exposed the ACCJC’s arbitrary and punitive behavior since they used a really heavy hand to restructure City College and attempt to remake it.

PRA: Several CCSF students were killed by the police between 2012 and 2017. Did activists want police violence to be integrated into the effort to save the college?

Legion: For many students, the death of CCSF student Alex Nieto was and is a major event. Even last month, at a rally, several students spoke eloquently about Alex and other students, Amilcar Perez-Lopez, and Sean Monterrosa, who were executed by police. After Alex’s death, radical faculty put up posters of him in their classrooms, but for other faculty, it was an event that faded from memory in the hailstorm of other bad news that impinged on their lives more directly.

Rein: Still, some students, staff, and faculty saw a clear line between funding police and cutting back on funding education. Their chant was: “young people deserve books, not bullets.”

PRA: After five years of non-stop work, in 2016, a Mansion Tax was enacted to make CCSF tuition free. Was this the movement’s most significant win?

Rein: We often ask ourselves what it means to have won. Yes, Free City, a tuition-free university for San Francisco residents, is the most inclusive college program in the country, and City College kept its accreditation and mobilized the support of an entire city. The corrupt leadership of the accrediting agency was pushed out. But the attacks on public education have not stopped either at CCSF or nationally. This March, City College’s administration announced its intention to lay off [about] 65 percent of the faculty. This would have cut hundreds of classes, affecting thousands of students. It would have gutted the school. The faculty union, AFT 2121, was in contract negotiations at the time of this announcement, and members approved a settlement on May 10 that averted layoffs in exchange for pay cuts of up to 11 percent. This buys time for more organizing.

Still, there’s been a shift in consciousness since the campaign began nine years ago. The campaign allowed for a great deal of leadership development. There is a lot of experience being carried forward and we have a better understanding of the root causes of the attack. We take heart from the organizing in K-12, especially the #RedforEd strike wave of 2018 and 2019. After a couple of decades of exposing those who are working against public education, that movement finally gained traction. We believe the same can happen for community colleges.